Harbergeorgism consists of a mixed economic model — that comprises both the Harberger and Georgist economic models — put together to attempt at new solutions (with Web3 technology as intermediary) on how to sustainably develop the new digital era and, ultimately, improve the physical world too.

From an economic lens, what should we focus on to get the best outcome in the digital realm? Can this digital revolution sufficiently translate to the physical reality, which badly needs innovation? What can we do to make it prosper again?

The Tokenization of Digital Public Goods & The Birth of New Crypto Goods

With the advent of publicly verifiable, digital encryption through blockchain technology, we’ve become able to authenticate, and, subsequently, tokenize scarce digital goods. In other words, this privatization (or tokenization) process was enabled by this technology and we’ve become able to turn digital public goods into digital private goods.

Taking into account the two main characteristics of a pure public good (non-exclusivity and non-rivalry), this blockchain revolution, as the foundation of a new system of property rights, has enabled the elimination of the two main problems that the original digital public goods posed, which were:

— The free-loader problem, which consists of people who want the good but avoid paying for it;

— The warranty problem, in which people who want a good and are willing to pay for it, but fear that others will not contribute enough to produce it.

This shift from public to private goods leads, in a way, to a market perfection, with respect to their owners being entitled to exercise private property rights, preventing those who have not paid for those goods from using them or consuming their benefits; and that the consumption by one necessarily prevents that of another.

Therefore, this on-chain authentication of property creates legitimacy, and this legitimacy could only be achieved due to these assets gaining attributes characteristic to private goods — those of being excludable and rivalrous.

An array of digitally scarce goods, then, have started to blossom. We can think, straight away, of a few categories:

- Tradable, non-fungible tokens (TNFTs, or simply the famous NFTs): such as a piece of art, a digital sports card, or a square meter of physical or virtual land, which can be traded (sold, rented out, leased, etc.) but are unique in their nature, and so, cannot be replicated;

- Non-tradable, fungible tokens (NTFTs): such as a course or degree in a given subject or area, which can’t be transferred, since it was you who took the course or degree, they’re unique to you; but it’s fungible because, certainly, many other people took them too;

- Tradable, fungible tokens (TFTs): such as cryptocurrencies, or mundane on-chain things like a car or a house, a table or a chair, which can be traded and are many of the kind;

- Non-tradable, non-fungible tokens (NTNFTs): such as an on-chain car license or an on-chain certificate of a biometric data exam (contrary to your biometric data which will become very sellable, but still non-fungible), which are not tradable, and surely are unique and irreplaceable.

Contextualizing Land & Assets

In this essay, we will focus on two types of property: land (which can be categorized as a classic NFT, since it’s a tradable, but irreplaceable good) and assets (which can be fluidly categorized as any of the above tokens, depending on the case).

While land is a type of asset — for the purpose of proper theoretical experimentation herein — we’ll disentangle them, and categorize them a bit differently: as unearned and earned sets of goods, respectively, in productive and ownership terms.

In the “real” world, proper land use seems to be one of the biggest missed opportunities for the betterment of overall societal and economic welfare. Much of the current state of stagnation in innovation and even overall deterioration in the last half-century has been due to, mainly, non-sensical zoning laws (which did centralize too much of the power on the landowners), and hyper-environmentalist trends that constrain any type of innovation that could be made. All this, naturally, led to very distorted outcomes.

The up-and-coming Web3, and its pegged technology, presents, I think, a serious and momentous opportunity to rethink this problem.

Thinking right into the future: by the end of this decade, we’ll have eight different types of land:

- Centralized, physical land: as we mostly know it now as; owned by a landlord;

- Centralized, virtual land: as on a Web2 game like Minecraft or FarmVille; owned by a company, like Microsoft and Facebook, respectively, in these cases;

- Decentralized, physical land: as where Georgism is pragmatically applied (or approximate derivations thereof); effectively owned by the citizens of the city or country;

- Decentralized, virtual land: as on the Metaverse;

- Decentralized, on-chain ownership of physical land: as the fundamental component of a Crypto City;

- Decentralized, virtual land as a proxy for the corresponding physical land: as a mix of the Metaverse and the Crypto City lands;

- Lunar land: model TBD;

- Martian land: model TBD.

As for assets, in general terms and properly understood, are valuable goods from which their owner expects to derive future economic benefit from.

Crypto assets are just that but digitally encrypted on a blockchain; and their categorization can, as well, possibly vary through all the four categories of crypto goods we’ve seen above.

Thinking of the six different types of assets we can have, by the end of this decade:

- Centralized, physical assets: as it’s most common; owned by an individual;

- Centralized, virtual assets: as a tool, or a vehicle, or a farm on a Web2 game like GTA or FarmVille; owned by a company;

- Decentralized, physical assets: as where Harberger taxation would be (or is) pragmatically applied (or approximate derivations thereof); effectively, partially and commonly owned by the community;

- Decentralized, virtual assets: as on the Metaverse;

- Decentralized, on-chain ownership of physical assets: as an on-chain contract that attests one’s ownership of the physical asset;

- Decentralized, virtual asset as a proxy for the corresponding physical assets: as in remotely operating a virtual machine (a tractor or a bulldozer, for example) and have it perform exactly the same way in reality, with the corresponding real machine. (Interesting innovations and improvements in the agriculture or supply chain sectors could be done this way.)

All around, we’ll explore and lay out how land and assets can be thought of through the Georgist and Harberger perspectives, respectively, and in the contexts of both Crypto Cities and the Metaverse.

I’m interested in exploring different ways to think about them, improve our understanding and use of them, and explore ways of, ultimately, potentiating development in real land and property in the physical world, in these new contexts. So, let’s do it!

Georgism & Harberger Taxation

Georgism

Pioneered by the late 19th-century American economist Henry George, Georgism proposes a single tax applied to the ownership of land (and its respective natural resources) — the so-called Land Value Tax (LVT) — which aims at taxing unearned wealth, rather than earned wealth.

Starting from an ethical lens, people had no hand in creating land — it’s a natural blessing —, therefore they should have no moral right to own it, in the sense of getting profits simply because they own a piece of the land. However, they did create the improvements upon it: the infrastructure, the crops, and so, if they have a moral right to keep what they produce with their labor, they should also have a moral right to own those things, and, eventually, economically benefit from them.

Traditional property taxes are a disincentive on construction, maintenance, and repair since they increase in accordance to property improvements.

A LVT is not based on how well or how poorly land is actually used; since the supply of land is essentially fixed, land rents depend on what tenants are prepared to pay, rather than on landlord expenses, which should prevent landowners from passing the LVT to the tenants. The tax burden cannot be passed on as higher rents to the residents.

Consequently, under this model, neither land value nor land rent can be determined by a landlord. They cannot artificially inflate the value of the land in order to make a profit.

The value of land is related to the value it can provide over time, and it can be measured by the rent that a piece of land can rent for on the market. If you think of it, the present value of rent is the basis for land prices.

A LVT would reduce the rent received by the landlord, and thus will decrease the price of the land, holding all else constant. The rent of land is the exact market value of the advantages that the whole community has provided to the holder of that site; it is the fund that society should collect for public revenue.

A LVT is a progressive tax based on the quantity and value of the land that is owned.

Unlike property taxes, it disregards the value of buildings, personal property, and other improvements to real estate. The tax burden falls on titleholders in proportion to the value of the locations.

This framework would also discourage speculative landholding because the tax increases as the land becomes more valuable, encouraging landowners to develop or sell vacant or underused plots of land that are in high demand, and thereby leaving more money for productive allocation of capital investment.

In sum, what Georgism proposes is this single tax on the ownership of land and the abolishment of all the taxes that hinder production. Then, the revenue collected from this tax, which is argued to be more than enough for a government to fund all services, could then be redistributed to all citizens in the form of a UBI (Universal Basic Income).

Harberger Taxation

Created and proposed by another American economist, in the 20th-century, Arnold Harberger, Harberger Taxation is an economic model of taxation in which asset owners self-assess the value of their own asset and pay a tax on that value per year; and at any point in time, anyone else can buy the asset from the owner at that self-assessed price, forcing a sale.

The source of misallocation comes when the owner of private property will “hold out” for a (sometimes monopolistic) price which the interested buyer may not be able to pay, leading to a delay or a failed transaction, even when the buyer could use the property more productively than the owner can. In other words, we could more readily and efficiently allow the market to allocate property to productive owners.

Logically, therefore, an owner is incentivized to set a low price to minimize the amount of tax they have to pay. At the same time, the owner wants to set a price high enough to discourage someone else from buying it away easily. The whole incentive is for owners to price an asset at a value that they are willing to pay to keep it.

Naturally, we may pose the question of how to allocate those assets efficiently to productive members of a community with scarce assets: exclusive ownership of a community asset could be taxed, ensuring that those who value it the most have access; and failing to pay this tax would trigger a forced auction (for example) of the asset that all community members could participate in.

Besides the more productive utilization of the assets, this framework would also raise substantial additional revenue for public funding.

Practical Teleologies

Georgism

Georgism essentially says that we should confiscate land and not property; and that taxing the value of land is the most logical and sensible source of public revenue because the supply of land is fixed and its location value is created by communities and public works.

An economic effect of the implementation of such tax would be (and in fact is) the increased attraction of the given location to investors and citizens since it would offer better opportunities than other places they could go. Hence, a direct consequence of this property tax shift is that the demand for land goes up, and if the increase in land value is greater than the increase in LVT, land prices will also go up, making the LVT also go up; subsequently, also the revenue derived from the local or federal government would increase.

Other types of unearned wealth that could fall under this single tax could be inheritances, profits derived from market-trading with financial instruments or with dodgy methods like short-selling, or profits derived from data collection by Big Tech companies.

A measure that would be in line with this one would be the inclusion of social transportation under public funding (many Georgists argue), which would incentivize the free movement of people, without having the handicap of rising rents impeding their decision.

In sum, people should be allowed to keep the wealth they create themselves, but economic value derived from land should belong equally to all members of society, and therefore should be mostly taxed away from the owners of those unearned assets.

The LVT (and the subsequent UBI policy) generally reduces economic inequality, removes incentives to misuse real estate (and land, by proxy), and reduces the vulnerability of economies to property bubbles and their collapse.

Possibly the biggest obstacle to the implementation of this framework, thus far, has been that landowners often possess significant political influence, through their enhanced financial capacity for lobbying.

Harberger

The whole teleology of this theory is for private assets to be more productively utilized by society, it aims at keeping the power of the market, whilst reducing the inefficiencies in how property is currently allocated.

At a relative cost to efficiency in investment returns, it reduces the prevalence of monopolies that exclude society from assets’ wealth-generating capabilities. Society, as a whole, would most benefit from this improved allocation of property and assets to the productive members of society that value them the most, because they can utilize them to derive greater revenue from them. In other words, it reduces investment efficiency at a gain in allocative efficiency to ownership, resulting in larger welfare gains.

This economic framework provides a way for us to understand and predict the evolution of market technologies (produced by the private sector) and property rights (produced by the public sector).

Harberger Taxation promises to democratize the control and ownership of assets.

By the late Adam Smith’s standards, a sensible model of economic taxation that would serve as a good source of public revenue should:

- Bear as lightly as possible on production;

- Be easy and cheap to collect;

- Be certain, predictable, and understandable;

- Bear equally: give no one an advantage.

Georgism and Harberger Taxation, as we have observed, pretty much tick all the boxes on their own, but aggregated and joint with the advent of digital cryptography could make the outcome be even more efficient and promising.

Both these theories, while with some narrowly successful, real-world cases so far, have largely been hidden and obscure in regards to their implementation. However, with new realities and possibilities being created and explored today, we have an amazing opportunity to start anew.

Harbergeorgism & Web3

To help us navigate what’s following, it’s important to lay out what Web3, DAOs, a Crypto City, and the Metaverse, as we understand them today, are:

- **Web3 **is the next phase of the Internet in which its network is owned and controlled by its creators and users, meaning, it is decentralized from any central authority. Obviously, blockchain technology is the great enabler of this new digital era that’s upon us; and the privatization/tokenization of digital goods — through “smart contracting” —, which we referred to in the beginning, is a core property of Web3.

- DAO (Decentralized Autonomous Organization) is a digital organization — either operating in a real or virtual environment — that’s automated, decentralized, and community-led which has no central authority, either. Smart contracts lay the foundational rules, execute the agreed-upon decisions, and, at any point, proposals, voting, and even the very code itself can be publicly audited.

- A Crypto City is a new or existing physical city funded and operated, in a decentralized manner, with one or several cryptocurrencies, by a local government or a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO).

- The Metaverse is a shared digital reality that allows users to interact multidimensionally in an immersive virtual environment from whichever real, physical place they are at.

So, all-inclusive, Georgism applies to unearned wealth, and Harbergerism applies to earned wealth (but the one economic benefit could be derived from, i.e., assets). Both, as they traditionally are, decentralize control and ownership, and offer sensible solutions for efficient allocation of scarce property and resources.

Harbergeorgism, then, aims at striking a balance between private and common ownership, i.e., a balance between the right incentive structures for the public sector (Georgism) and for the private sector (Harberger Taxation).

Borrowing Balaji Srinivasan’s insight: “There are only two ways to make money in business: bundling and unbundling.”

While making money is off-topic here, this bundling-and-unbundling idea provides some interesting thought experiments. Balaji has exemplified such an experiment, in a recent Tim Ferriss podcast, and added a twist:

“You take the songs off of a CD, you unbundle them into MP3s, then you rebundle them into Spotify playlists. Or you take the articles of a newspaper, and you put them into individual URLs, then you rebundle them into Twitter feeds.”

Similarly and extrapolating to the case in point: both Georgism and Harberger Taxation can be seen as a shift from centralization (landlord- or monopolist-based) to decentralization (community-based), so it switches from bundling to unbundling. The rebundling part would be the creation of a community-focused, decentralized organization stepping into the frame to implement this framework in a new way — like a Crypto City or a Metaverse run by a DAO.

The Harbergeorgist model implemented by a decentralized organization (like the above one), would provide it a framework to: firstly, make a return both on their investment in the public goods, and in generating revenue to distribute to the community; and, secondly, to benefit individual agents, since they would as well benefit from the better allocation of the community assets and from the “fairer” pricing structure (which would, as a consequence, also contribute to general welfare).

Harbergeorgist Tax Formula for a DAO’s Economic Inputs & Outputs:

Harbergeorgist Tax (Land Value Tax + Harberger Tax) = Public Funding + UBI (if leftover)

Making Harbergeorgism Work Upon Crypto Cities & the Metaverse

As a recap, blockchain technology offers the Harbergeorgist model a testing ground for more efficient experimentation in a decentralized, publicly-verifiable contract society, where rules can be enforced using only smart contracts; and with this experimentation in course, new forms of ownership for land and scarce assets can be tried out on Crypto Cities and the Metaverse.

As we’ll see throughout, a lot of the same logic can be applied for both, in their respective contexts.

Crypto Cities

In a recent essay, Vitalik Buterin addresses Crypto Cities (recommended read), where he argues that this is an idea whose time has come, and which has been gaining traction due to two relevantly recent trends: the growth in interest in local governments and the now more-widespread debate on crypto ideas.

As a matter of fact, the COVID-19 shock has triggered all sorts of new global paradigm shifts like remote work coming to stay, like the Great Resignation, or like locations starting to become more focused on shared beliefs (the future Networked Countries), rather than on shared geography.

In view of that fact, largely, the greater flexibility and genuine capacity for dynamism and efficiency in new experimentation — compared to national or federal governments — has sparked a growing interest in local governments.

Drilling down on the last point: if geographic relevance has decreased in demographic and work-related terms (“demonopolization” of population density in urban areas, e.g.), then the role of legacy cities and states, in general, has also subsequently decreased, so their fundamental role seems now somewhat off and should be rethought.

A skilled and financially independent professional can change the law under which they live currently, simply by moving to a more advantageous jurisdiction of their choosing. A non-dependency on election cycles for policy change gets then established.

In order to gather great talent, it’s not enough anymore to have great local incentives or benefits, such as built-in local reputation, strong in-city network effects, or nice places to hang out on the weekends. Emigration of the most talented (particularly) will discipline city governments.

Cities and states will be in direct competition for talent with other cities and states (soon countries vs. countries).

This societal phenomenon represents a major macroeconomic and geopolitical shift.

The most successful cities and states will be run by software-savvy leaders; and, if they fail to adapt, citizens leave. Just like non-software-savvy companies, this century, have crumbled starkly or simply went out of business (e.g. Blockbuster, Nokia, Kodak, or General Motors); they failed to adapt, and their consumers left.

What can cities and states then do to adapt to this new norm?

Well, primarily, it won’t start out with the inner reformation of zoning laws in existing legacy cities or states. The real innovation will take place in new places first (new cities being built), and then spread out to “established” cities. Such will happen precisely when legislative bureaucrats will feel the need to implement the outer-successful reforms because, otherwise, their jurisdiction will severely lag behind.

So, they can specifically start learning about, investing themselves, and gradually becoming Web3/crypto-savvy.

Miami’s Mayor Francis Suarez did the kick-off already:

At a first glance and as a way of getting at it, it would be suitable to start by creating a divisible, tradable, fungible city token backed by “shares” of land (or square-meters, rather) that residents could hold as many units of as they wanted or could afford. Somewhat similar to gold-backed currencies.

Such would become the Georgist medium of exchange — the starting point from which the Georgist theory could be implemented.

Then, the Community Leader could give primacy to an efficient allocation of assets over their investment efficiency, which is what ends up mattering medium- and long-term, thus, positively impacting the sustainability of the community resources.

The DAO (referred from here on out as a proxy for the leading organization in the real and virtual dimensions) could implement this decentralized, rebundled, and hybrid model, which would enable them to both make a return on their investment in the public goods and also in generating revenue to distribute to the community (through LVT revenue); and, additionally, to benefit individual agents, since they would as well benefit from the better allocation of the community assets and from the “fairer” pricing structure (through Harberger Tax revenue).

This revenue would help the decentralized organization in the funding of all sorts of public services, in a cryptographic, publicly-verifiable way; and would then distribute the leftover revenue (profit) as a UBI for city-coin holders, which would also serve as an incentive for people to get the city-coin and fund their local form of government.

As the DAO keeps reinvesting those funds, it will be able to derive progressively greater revenues (from the increased LVT), because as the city prospers, the land value also increases, and thus the city coin value, as well.

Two important points to keep in mind for a new city are:

- On loyalty and speculation avoidance: an incentive structure — built into an on-chain smart contract — should be thought of for city-coin holders to commit to holding the city coin for a certain period. This way, we could prevent harmful land speculation.

- On overly benefitting early adopters: the city could fall into the trap of too quickly sacrificing optionality by selling off too much territory, sacrificing the entire upside to a small group of early adopters. Even if this happened, with the LVT in place, those early adopters would have a counter-incentive to properly use the land. While ways should be thought through to prevent that, LVT alone (followed by the UBI policy) would solve the early-adopter vantage problem. Because, unless the land is usefully utilized, the landowner will carry a loss from the incessant burden of this tax. As for UBI, the entire community would benefit, making LVT also a quite egalitarian tax in this aspect.

Metaverse

While the similarities are starker than the differences, the Metaverse does differ from a Crypto City context in obvious ways: it isn’t subjected to infectious diseases, human inefficiencies, delays, and other prejudices. It’s a completely brand new reality. There are no reformations to be done. There’s simply a blank slate from which we can strive for our imagination and logic and create something new.

City-Coin Economics & Incentives

As per Vitalik’s aforementioned essay (Crypto Cities), he raises very good points on what a sensible and potentially successful economic model, and its pegged city token, in this context (although some points can be analogized for a Metaverse context too), should aim at:

— Get sustainable sources of revenue for the government. The city token economic model should avoid redirecting existing tax revenue; instead, it should find new sources of revenue.

— Create economic alignment between residents and the city. This means first of all that the coin itself should clearly become more valuable as the city becomes more attractive. But it also means that the economics should actively encourage residents to hold the coin more than faraway hedge funds.

— Promote saving and wealth-building. Home ownership does this: as home owners make mortgage payments, they build up their net worth by default. City tokens could do this too, making it attractive to accumulate coins over time, and even gamifying the experience.

— Encourage more pro-social activity, such as positive actions that help the city and more sustainable use of resources.

— Be egalitarian. Don’t unduly favour wealthy people over poor people (as badly designed economic mechanisms often do accidentally). A token’s divisibility, avoiding a sharp binary divide between haves and have-nots, does a lot already, but we can go further, eg. by allocating a large portion of new issuance to residents as a UBI.

One pattern that seems to easily meet the first three objectives is providing benefits to holders: if you hold at least X coins (where X can go up over time), you get some set of services for free.

As well as proposals for the correct set of right incentives for city-coin holders:

— Create an incentive to hold the coin, sustaining its value.

— Create an incentive specifically for residents to hold the coin, as opposed to otherwise-unaligned faraway investors. Furthermore, the incentive’s usefulness is capped per-person, so it encourages widely distributed holdings.

— Creates economic alignment (city becomes more attractive -> more people want to park -> coins have more value). Unlike home ownership, this creates alignment with an entire town, and not merely a very specific location in a town.

— Encourage sustainable use of resources: it would reduce usage of parking spots (though people without coins who really need them could still pay), supporting many local governments’ desires to open up more space on the roads to be more pedestrian-friendly. Alternatively, restaurants could also be allowed to lock up coins through the same mechanism and claim parking spaces to use for outdoor seating.

Another idea that is more viable in the short term is subsidizing local businesses. (…) Businesses produce various kinds of positive externalities in their local communities all the time, and those externalities could be more effectively rewarded.

And also adds:

“One excellent gold mine of places to give city tokens value, and at the same time experiment with novel governance ideas, is zoning.”

Throughout the reading of the above points, the application of Georgism must have really rung a bell. In fact, pretty much the whole essay can be seen as a Straussian interpretation for the advocation of Georgism in solving a lot of challenges for the up-and-coming Crypto Cities and Metaverses.

What could be added to Vitalik’s points to make them even more robust would be the Harberger model, since it would, as well, create economic alignment between residents and the city, in part because it would encourage sustainable use of resources, would provide sustainable sources of revenue for the government, and would be egalitarian.

More ideas for incentives and initiatives will be presented in the next section, where we’ll do three detailed example scenarios.

Envisioning Three All-Encompassing Scenarios Amidst Implementation of the New Framework for Both Realms

For starters, let’s suppose there are X square meters of idle land in a certain city.

Right on, the city-coin holders (with their land-backed city coins) and a business owner would be incentivized to properly use that vacant land: in the case of the business owner to set up a venture, knowing in advance the advantageously long-term economic structure, and in the case of the city-coin holders to derive ground-rent to fully cover the LVT (otherwise, they would have the recurring burden of that tax crippling their finances) and obtain extra revenue.

The funding options available to the business owner to build the infrastructure or implement the service would be numerous, but focusing on the most relevant (and pragmatically the best, ultimately) for this context: the setting up of a crowdfunding campaign participated in by a given number of interested city-coin holders through the on-chain purchase, with city tokens, of a “share” (i.e. an NFT or portion thereof, in this case [which would provide proof of ownership for these city-coin holders]) of the building plans or of the mockup, for example.

These NFT investors, naturally, have a vested interest in the development of these infrastructures and activities, since they would improve the inner economy, and thus, the prosperity of their residential area (since they are, also and primarily, city-coin holders), and also themselves financially, ultimately.

Following, we’ll picture three different examples of infrastructures to fund and build: an industrial farm, a residential building, and a basketball stadium.

The Unsuccessful Scenario

Now, if the crowdfunding campaign is not successful in its implementation and/or ability to generate enough interest, the business owner and city-coin holders would part ways, and another deal would be arranged to allocate that land to another person who would be better suited to make greater use of it.

If it were successful in this initial step, but if, afterwards, the business owner of the farm, building, or stadium was misappropriating/mismanaging/misusing the infrastructure, which would, in effect, hinder the business, the Harberger tax which would be in place (proportional to the asset’s latest valuation) would be too high to cover for the lagging revenue, and the owner would be “forced” to drop the estimated value of the asset’s asking-price, in order to, also drop the tax being exerted (again, since it’s proportional to the valuation). This price drop would make it “more accessible” to potential buyers or investors, who would see a business or investment opportunity.

Succinctly, the Harberger tax would “keep things in check”: it would give useful pointers on the business and its management performance.

In this case in point, the Harberger premise wouldn’t be fulfilled: the asset was not properly allocated and was being poorly utilized.

The Successful Scenario

Conversely, if the crowdfunding campaign is successful and the construction gets up and running, then the LVT that’s in place is well covered by the city-coin holders since the business owner was bringing in income through rent.

The Harberger taxation logic, in a successful case, would come about as such: The owner of the farm, building, or stadium did set a high self-assessed price for the asset (making the Harberger tax proportionately high as well), because the business was doing so well. If this trend keeps on going he has the interest to keep setting up a high-asking price (since the tax increase wouldn’t be that much of a burden either), in order to keep away potential buyers. They would see that the asset was at a too high a price to ponder investing in it and, thus, they’d mostly stay away from jumping in to strike a deal.

The Harberger purpose, herein, would be fulfilled: the asset was properly allocated and efficiently being managed.

Subsequently, the revenue from the sale of the farm products, from the rents of the residential building, or from the basketball game tickets could then be paid off by the business owners as a royalty to the NFT investors who took the initial risk on the purchase of that NFT (or portion thereof).

On the DAO side, it also has a vested interest to fund and invest, adequately and thoughtfully, in local public services to improve the city, since the LVT received, in the end, would increase with that prosperity (because that investment would hike up land prices), generating greater revenues, and making the city upgrade as a result. This, in essence, public profit would be equally distributed to the city-coin holders directly, as a form of UBI.

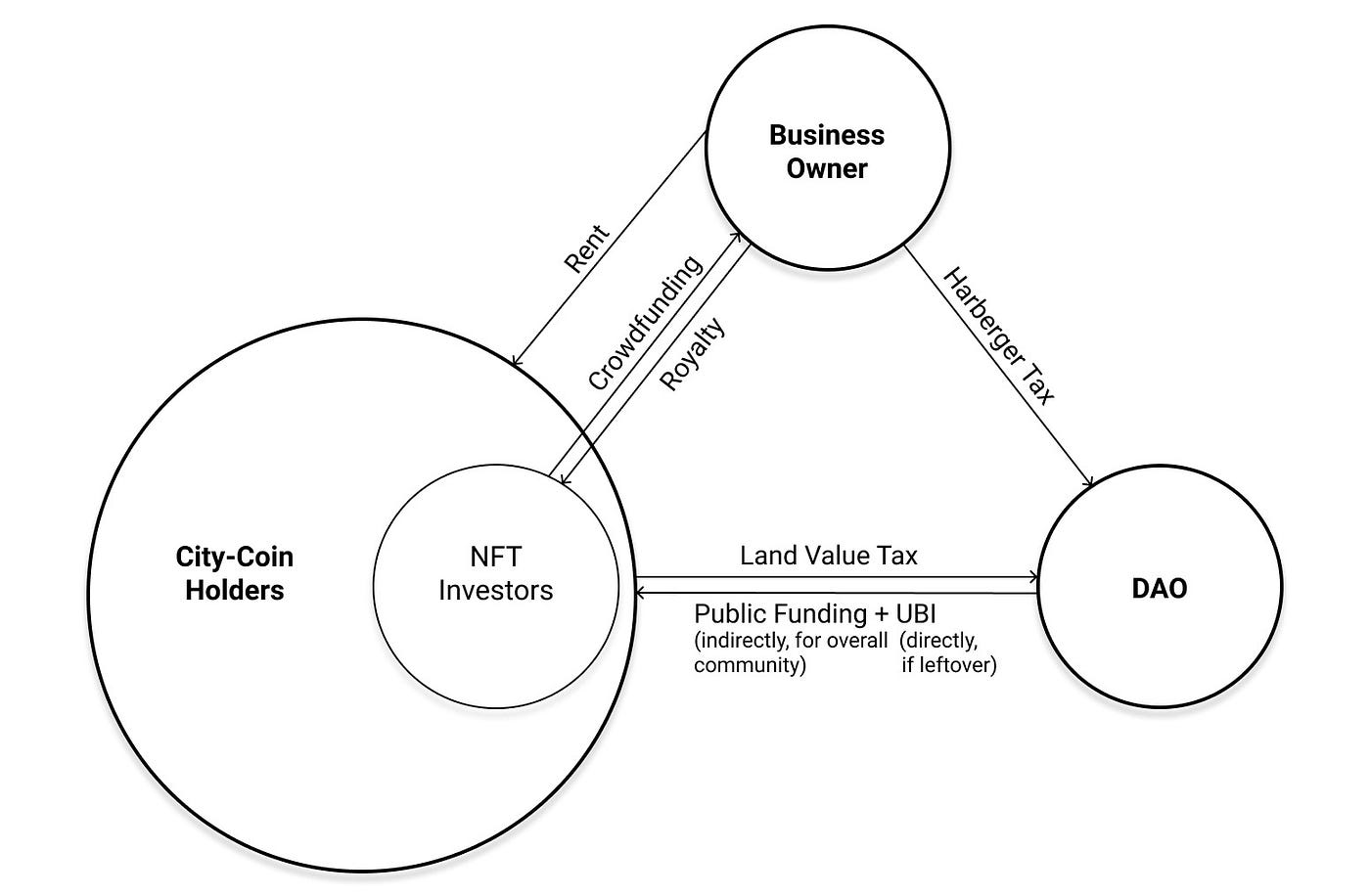

Transactions Streams’ Summary

As an overall transaction flow summary, we would have six main transaction flows (two of them being revenue streams that would go to the DAO [LVT and Harberger Tax]) that would be derived from the successful case:

- From the NFT Investors to the Business Owner: Crowdfunding;

- From the Business Owner to the NFT Investors: Royalty;

- From the Business Owner to the City-Coin Holders: Rent;

- From the Business Owner to the DAO: Harberger Tax;

- From the City-Coin Holders to the DAO: Land Value Tax;

- From the DAO to the City-Coin Holders: Public Funding (indirectly, for overall community) & UBI (directly, if leftover);

Further Incentives

The applications of city coins for local benefits, rewards, or access controls could be endless. Adding to the ones we’ve previously seen, we can further think of three examples:

— Economic incentive: Promotion of local-business shopping by attributing discounts if the individual is a city-coin holder (creation of economic alignment);

— Transportation incentive: Incentive for 2-wheel vehicle in-city transportation to make it pedestrian-friendly and also, green and public transportation, other than private and polluting transportation (pro-organizational and pro-environmental measure);

— Hygienic incentive: Reward for proper waste recycling (encouragement of pro-social activity).

As we’ve covered before, measures like these create loyalty from the part of the residents to the city, since they become directly aligned with its performance, outlook, and economically invested in it as well. They want to see the city succeed, because, then, they also succeed.

This is, essentially, how the economics of a Crypto City or Metaverse would play out under this aggregated model; they would display very similar economics, somewhat similar politics, and very different social dynamics.

“Real-World” Examples

Among the very early initiatives we are witnessing, we have:

Crypto-City Related

CityDAO

The plan for CityDAO is to start with a physical plot of land, and then add other plots of land in the future, to build cities, governed by a DAO, and make heavy use of radical economic ideas like Harberger Taxation to allocate the land, make collective decisions, and manage resources.

CityCoins.co

This is a project that sets up coins intended to become a local media of exchange, where a portion of the issuance of the coin goes to the city government. They’ve made the interesting decision to try to make an economic model that does not depend on any government support.

CityCoins communities will create apps that use tokens for rewards and local businesses can provide discounts or benefits to people who stack their CityCoins. MiamiCoin is trying to encourage businesses to do this, but we could go further and make government services work this way too.

Metaverse Related

Sandbox

The Sandbox is a virtual world built on the Ethereum blockchain, where players can build, own, and monetize their gaming experiences. The $SAND token is an ERC-20 utility token that is used for value transfers as well as staking and governance.

Decentraland

Decentraland is a virtual reality platform powered by the Ethereum blockchain. Users can create, experience, and monetize content and applications. One of the main features of the platform is the ability to purchase land (with $MANA coin) in its virtual reality & to build on it. Land in Decentraland is permanently owned by the community, giving them full control over their creations. Users claim ownership of virtual land on a blockchain-based ledger of parcels.

Furthermore, Adidas, Nike, Zara, Baidu, and Marriott (the largest hotel chain in the world), most notably, have entered the Metaverse already.

Conclusions

High-rising housing prices, overall inflation, supply chain and energy crises, political tensions, polarized societies, and generally apathetic economic growth are all main externalities of the lack of innovation and belief in technology we have been registering, over the last five decades, in Western societies.

Georgism’s goal is to combat economic inequality, poverty, and achieve *real* economic progress. Whereas, the main Harberger goal is the efficient allocation of resources within a community to, ultimately, achieve the best economic and societal outcome.

As there is the historicism of legacy cities for Crypto Cities, there is also the historicism of commonly-known Web2 virtual realities for a Web3 Metaverse. We shouldn’t mimetically project both in these historicist ways, but, rather, we should explore and develop them from a first-principles frame of thinking.

I believe the Harbergeorgist model properly conceives the best of both theories and offers a sound framework to apply to these new worlds in the making, to fulfill their best possible versions.

As outlined in this essay, we could have productive, prosperous, and wealthy societies that sustainably fund public services, reward the producers and risk-takers, benefit everyone equally, and look after the have-nots (apart from the general economic growth generated) by a form of guaranteed income, affordable shelter/housing and economic opportunities.

There’s a huge amount that can be done and that needs to be done, and we’re still very early, but, potentially with this method, we could start envisioning how the physical world could realistically improve through the digital revolution of Web3, which, all in all, constitutes a great potential turning point for us to reopen the frontier in the physical realm.