My senior year of college, a panel of VCs spoke to one of my finance classes. It was senior spring, so attention spans were at somewhat of a low. All classes were being conducted over Zoom, which also didn’t help. But in the middle of the discussion, Sarah Guo, one of the panelists, said something that struck me then and has stuck with me ever since: “understand the user that isn’t you.”

It’s worth mentioning that I take pride in my sense of individualism. I’m a twin, and I went to college with my twin, so I’m used to being (often unintentionally) paired with/compared to someone else. A constant desire to feel unique kind of comes with the territory. So trying to understand the user that isn’t me? Challenge accepted.

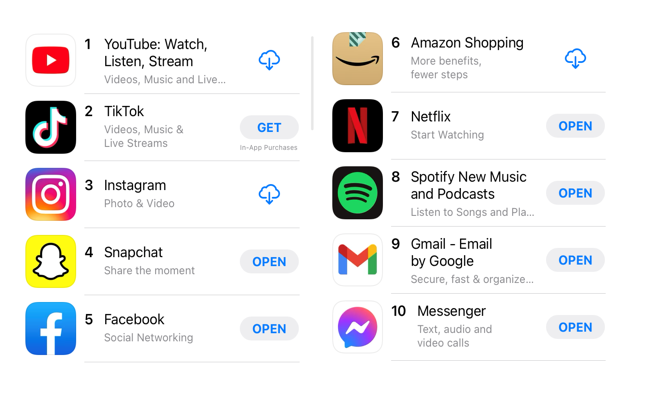

What followed was a few days of me looking at what apps I had on my phone, asking my friends what apps they had on their phones, looking at what apps were trending on the App Store, and trying to compare all three. I figured the apps on our phones — and the frequency with which we used each — were a good proxy for our habits as consumers.

There were a ton of commonalities: Uber/Lyft, Netflix, Facebook/Instagram, Amazon/Prime Video, Venmo, etc. As consumers, we had more similarities than differences. So much for my hope that I was a unique consumer.

Yet I also started thinking about why we had such a similar set on our phones — what these apps all had in common, why they had been so successful at replacing the incumbents that came before them, and what consumers may really want. This piece is an attempt to outline my (ongoing, potentially evolving) observations and answers to those questions. Below are some of what I’m calling my “always theses” — theses for what consumers will (almost) always want.

My senior year of college, a panel of VCs spoke to one of my finance classes. It was senior spring, so attention spans were at somewhat of a low. All classes were being conducted over Zoom, which also didn’t help. But in the middle of the discussion, Sarah Guo, one of the panelists, said something that struck me then and has stuck with me ever since: “understand the user that isn’t you.”

It’s worth mentioning that I take pride in my sense of individualism. I’m a twin, and I went to college with my twin, so I’m used to being (often unintentionally) paired with/compared to someone else. A constant desire to feel unique kind of comes with the territory. So trying to understand the user that isn’t me? Challenge accepted.

What followed was a few days of me looking at what apps I had on my phone, asking my friends what apps they had on their phones, looking at what apps were trending on the App Store, and trying to compare all three. I figured the apps on our phones — and the frequency with which we used each — were a good proxy for our habits as consumers.

There were a ton of commonalities: Uber/Lyft, Netflix, Facebook/Instagram, Amazon/Prime Video, Venmo, etc. As consumers, we had more similarities than differences. So much for my hope that I was a unique consumer.

Yet I also started thinking about why we had such a similar set on our phones — what these apps all had in common, why they had been so successful at replacing the incumbents that came before them, and what consumers may really want. This piece is an attempt to outline my (ongoing, potentially evolving) observations and answers to those questions. Below are some of what I’m calling my “always theses” — theses for what consumers will (almost) always want.

Each one’s core offering services at least one of the above consumer wants. Most service several.

These aren’t new themes. Bestseller lists and music rankings have existed for decades. Messaging platforms evolved from letters, to flip phones, to Blackberries and Motorolas, to all of the services we have today (Messenger, WhatsApp, Signal, Discord, Telegram, iMessage, etc.). Television became popular because it provided entertainment at the tip of your fingers. Sears gained popularity because its mail-order catalog improved aggregation, discovery, and convenience. People loved eBay and Craigslist because they provided opportunities to make a few extra bucks. You get the picture.

Many of these themes can be applied to crypto. It’s part of why we saw “consumer” chains like Solana and Avalanche take off in 2021 — Ethereum had high transaction fees, so people sought lower-cost options. It helps explain why DAOs are so powerful: they provide new, convenient ways to organize and communicate. (They’re also pretty entertaining). These theses help explain why OpenSea became the dominant NFT platform amidst heated competition from competitors like Nifty Gateway and SuperRare: OpenSea offered better aggregation, discovery, and curation.

These theses also shape what types of products and platforms I think have a good shot at winning the next decade in crypto (and elsewhere).

A few caveats

My hope is for this to age well, so I’ll add some caveats. There are instances where friction is good (email filters are a good example). There may be a limit to how much convenience we want; if given the choice between having an Uber arrive instantly vs. arrive in 5 minutes, most may prefer the bit of extra time (just as long as it’s not a 15-minute wait). Aggregation can lead to information overload. Low costs may make a network more vulnerable to hacks or spam. Etc.

Too much of one thing is rarely desirable. But as we adjust to new normals, our baseline resets and we start to want more. A decade ago, Amazon’s two-day delivery felt revolutionary — certainly faster than the standard 5-7 business day wait. Then people got used to two-day delivery, so Amazon began offering next-day delivery, then same-day delivery. Now companies like Coupang are offering deliveries in under an hour. As our baseline reset to faster and faster deliveries, companies (re)gained a competitive edge by incrementally improving convenience.

It’s really hard to go in the opposite direction. Instagram is and always has been a free service. Even at its peak, if they had tried to charge a platform fee — even for as low as $1/month — there’s a good chance many users would have exited.

The above “always theses” of consumer wants also always include trade-offs, of which one of the biggest is experience. Watching a YouTube recording of a concert is certainly more convenient (and cheaper) than going to an actual concert, but the experience isn’t the same. Finding a new song via Spotify’s “top hits” playlist and recommending it to your friend — only to find out your friend found it, too — may not be as satisfying as sharing a niche record only aficionados could have discovered. Companies/products/platforms that can reduce this trade-off while sufficiently meeting the rest of customers’ desires also tend to do well.

There are other trade-offs, like security and flexibility. Places we accept relatively greater inconvenience and higher fees are often areas where there’s a higher degree of risk. Aggregation can increase switching costs, just as relying on a couple of platforms for income gives them greater leverage in levying take rates. These trade-offs are important regardless of whether one is evaluating new social networks, new cloud software, or new protocols.

There are always trade-offs. Figuring out which aspect trade-off matters more to the customer is part of the process. Context matters and, while it doesn’t have to be a case-by-case basis, I imagine some industries consistently swing more in favor of one trade-off vs. the other (e.g., security is very important when conducting major financial transactions). I know it’s kind of a cop out to say “it depends” but, unfortunately, it does. Still, I think these act as a good framework for what consumers will (almost) always want.