What yours is worth and why it matters

Co-written with Liam Donohue, with revisions by Noam Levenson and Omid Malekan.

Originally published on Hacker Noon.

Big Facts

Focus on the relationship between these two statistics:

- 91%** of 18–34 year old consumers trust online reviews as much as the recommendations of their friends and family. **

- ~50%** of online reviews accurately reflect the quality and value of the product/service being reviewed. **

All numbers point to one important truth about online opinions: we all care about them deeply, base decisions on them, yet they’re largely inaccurate.

When information is limited, humans tend to turn to whichever signals they consider to most directly reflect the subject at hand. When it comes to online reviews, star ratings are king, helping users determine the value of products on Amazon, locations on Google Maps, businesses on Yelp, and riders/drivers on Uber, among many others.

Unfortunately, they’re just not that accurate. Several CU Boulder Professors analyzed 1272 Amazon products’ user ratings and concluded that reviews often lack convergence with more vetted quality scores or the ability to predict resale prices. In summary, the researchers argue that there is a “substantial disconnect between the objective quality information that user ratings actually convey and the extent to which consumers trust them as indicators of objective qualities.”

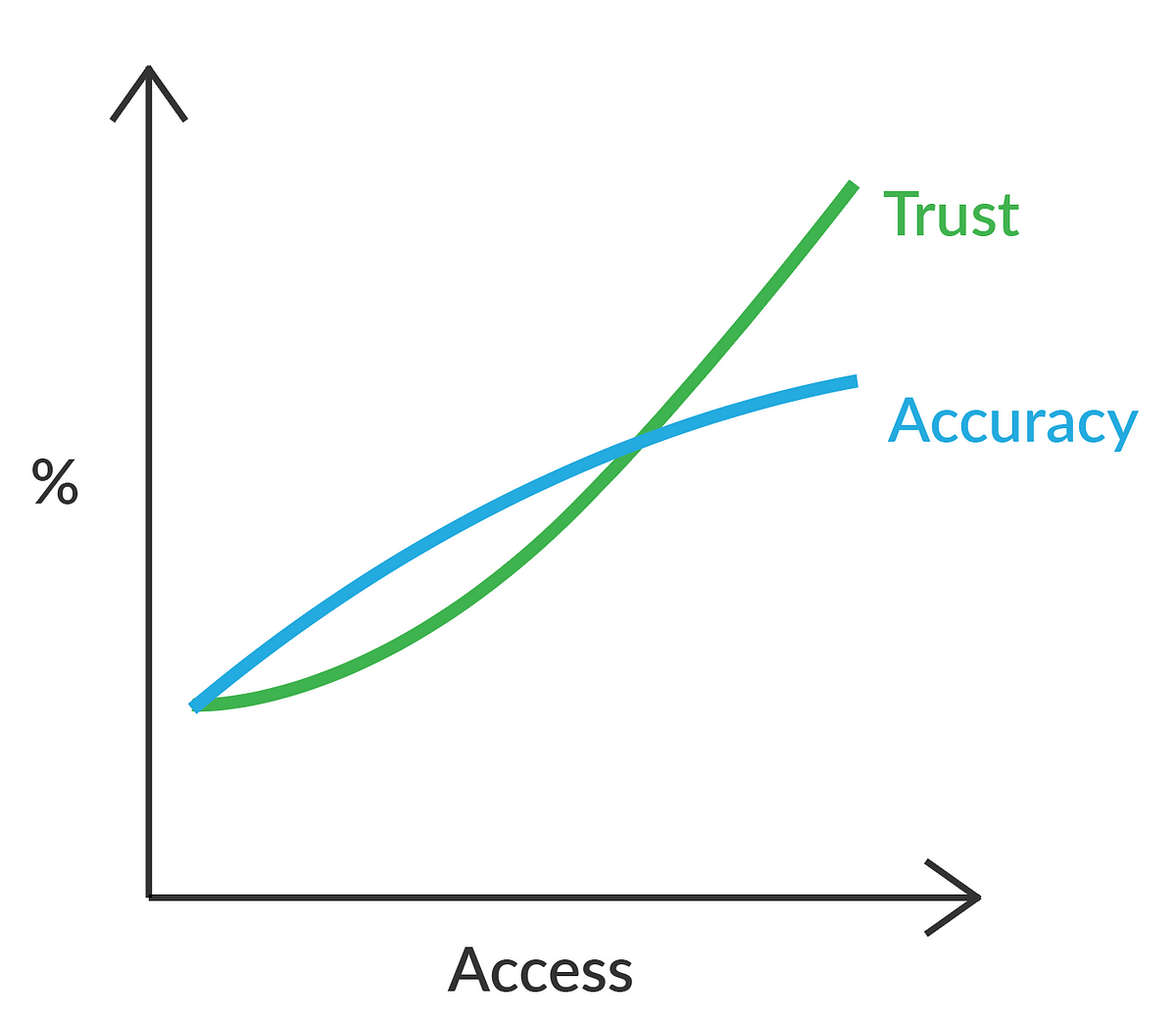

We theorize that this disconnect between trust and accuracy is a factor of the changes in access that occurred as a result of the rise of the internet. Access in this case refers to both the ability for anyone to rate products/ services/ content and the ability to see more ratings online. We believe that the growth of access first lead to an increase in both trust and accuracy but, over time, reduced the reputation at stake and lead to a divergence between trust and accuracy. (more on this later)

Does this failure to accurately predict quality betray humanity’s careless impulse towards simple visual representations? Or is this indicative of our over-reliance on a perceived consensus on opinions that is far less effective than we realize? Let’s begin.

#OpinionsMatter

There are few things more valuable to us than the opinions of others.

We have increasingly relied upon the opinions of others to direct our decisions. Some powerful opinions can make a dramatic impact, like the Oprah Effect, whereby products regularly see a significant boost in sales following a public endorsement from Oprah Winfrey. More often, however, they come from the general public, as is the case with ecommerce product reviews like Amazon, Ebay, and Walmart.

A highly-cited Harvard Business School study from 2011 estimated that a one-star rating increase on Yelp translated to an increase of 5% to 9% in revenues for a restaurant. Cornell researchers found that a one-star change in a hotel’s online ratings on sites like Travelocity and TripAdvisor is tied to an 11% sway in room rates, on average.

The internet’s peer-to-peer nature is a huge reason for this, as opinions have become more accessible. In a study done by Zendesk, 88 percent of customers read an online review that influenced their buying decision. Average user rating has become a huge driver of sales, and now, user-generated ratings and narrative reviews can be found on almost every website that sells something.

However, reviews and ratings impact more than just customers’ buying decisions; investors and partners look at a business’ reviews too, in order to gauge how a brand or company is being received by the public. Investors trying to wrap their head around a business will look at their product’s reviews “100% of the time,” according to Forbes research.

The Colorado University study argues that the average consumer is under the assumption that “we are entering an age of almost perfect information, allowing consumers to make more informed choices and be influenced less by marketers,” largely due to the “proliferation of new sources of information.” However, the research also suggests that we assume that user ratings “provide an almost perfect indication of product quality with little search cost . . . consumers now make better choices, are more rational decision makers, less susceptible to the influence of marketing and branding.” But in addition to that, “consumers fail to consider these issues appropriately when forming quality inferences from user ratings and other observable cues. They place enormous weight on the average user rating as an indicator of objective quality compared to other cues.” This, we argue, has to do with the search costs of finding valid information on reviews.

Fake it till you break it

“More people are depending on reviews for what to buy and where to go, so the incentives for faking are getting bigger… It’s a very cheap way of marketing.” — Bing Liu, Professor at University of Illinois

Fake activity, bots, and trolls aren’t new to the internet, nor are they new to our written content (See: The Influencer’s Dilemma). But in the case of opinions, they take on a slightly different form.

Opinions should drive the progress of products and services. Business plans should be centered around providing goods that consumers want and like. If online referendum were accurate, businesses would have to develop products more than they market them. But if opinions can be manipulated, higher returns can be earned by focusing on reviews as a marketer-controlled variable (something that marketers can control and manipulate for a price).

In the internet age, reviews have very much become a form of marketing and has evolved into an enormous business: reputation management. Companies need reputations, and reputations come from people, unless you can buy them for cheaper than an ad campaign.

Fakespot, a ratings analytics tool, estimates that 52 percent of Walmart reviews and 30 percent of Amazon reviews are fake or unreliable. A recent ReviewMeta analysis determined that in March of 2019 alone, Amazon was hit with a flurry of more than 2 million unverified reviews (that is, reviews that can’t be confirmed as purchases made through Amazon) — 99.6% of which were 5 stars. Most were ratings of off-brand electronics products.

Once we recognize the enormous incentives behind fake opinions and the ease with which people can create them, it should become quite difficult to trust review sites. Review boards, once populated by a swath of genuine do-gooders, have transformed into sinister armies of would-be bots and paid actors. That sweet grandma raving about her favorite brand of cookies? That’s probably a powerful bot farm connected to all sorts of notorious online activity. The top rated professor on RateMyProfessors.com at Columbia University? She likely filled out most of the reviews herself. And the most rated CU professor on the site? Ted Mosby from How I Met Your Mother. Just for fun, I’ve also added Rick from Rick & Morty to the site as a CU physics professor.

Review Bombing

Of all the ways to utilize fake reviews to manipulate outcomes, review bombing has to be the funniest. It’s the simple act of many users/accounts flooding a product with poor reviews to make it seem unappealing to the general public. Kind of like a “Sybil Attack” of opinions.

Just hours after Hillary Clinton released her memoir What Happened, detailing her experience in the 2016 campaign, “hundreds of one-star reviews” appeared on the book’s Amazon product page.

The book’s publisher expressed to the Associated Press: “It seems highly unlikely that approximately 1,500 people read Hillary Clinton’s book overnight and came to the stark conclusion that it is either brilliant or awful.” Quartz wrote that of the 1,500 reviews, “only 338 were from users with verified purchases of the book.”

Hillary isn’t the only victim to this kind of attack. Firewatch, the indie adventure video game, was review bombed after their removal of famous gaming YouTuber PewDiePie’s let’s-play account. Firewatch utilized DMCA copyright laws to remove his content, and fans of PewDiePie didn’t like this “support of censorship”, so they chose to review bomb the game on Steam. Our favorite review was: “At least one of the game devs seems to be a DMCA abusing SJW crybaby who is using copyright laws to wrongfully take down videos if the reviewer uses a word he doesn’t like.”

Remedies

Some platforms have taken steps to filter out this type of behavior by requiring certain costs for users to review. AirBnB, for example, will only let you review places that you’ve stayed at. Amazon attaches ‘Verified Purchase’ tags to reviewers who’ve purchased items. These actions do a solid job at filtering out some of the noise, but are still quite easy to manipulate. I know because I did this for my brother’s AirBnB listing. I booked it for the night, my brother Venmo’d me back the money, I left a great review, and AirBnB made 3% on the transaction (~$1.20). But this unicorn isn’t the only resort site that has this problem. Researchers at Yale, Dartmouth, and USC found evidence that hotel owners post fake reviews to boost their ratings on TripAdvisor and Booking.com, who run the same ‘verified purchaser’ filtering. They ran a similar scheme to mine: the owners booked rooms for themselves and then proceeded to give their own hotels 5 star reviews. These loopholes are part of a bigger failure to reflect the individual *value *of a review that is necessary for more accurate reviews and results.

When Everyone’s Super, No One Is

The notion that all opinions are created equal online is a large reason for the inaccuracy of opinions.

Let’s pretend you’re searching for an Italian restaurant in New York for a date with your significant other tonight. Actually, let’s first pretend you indeed have a significant other (and aren’t forever alone like me), and then let’s pretend you’d like to take them out.

Whose opinion would you trust more when choosing a restaurant? Michelin star chefs from New York or random tourists on the internet?

Hopefully you chose the chefs, at least if you were certain they weren’t bribed to lie. Now let’s say you’re looking to buy your (imaginary) loved one a diamond ring. Do the chefs have any unique expertise that would serve you on this search? Probably not.

The moral of this romantic story is that opinions aren’t democracies; we shouldn’t all get an equal say as to the subjective quality of products, venues, or anything else for that matter. What we need is more of a meritocracy, because some of us have earned the right to speak on certain topics with authority, not necessarily through a college degree or an award but could simply be receiving the continued approval of the online community. Today, most sites that you visit treat everybody equally and give their opinions equal reign on any and all subjects. This one-person-one-vote model just doesn’t make sense for diverse decision-making, because it doesn’t distribute accurate weight to the expertise of various participants.

Attempts at Reputation

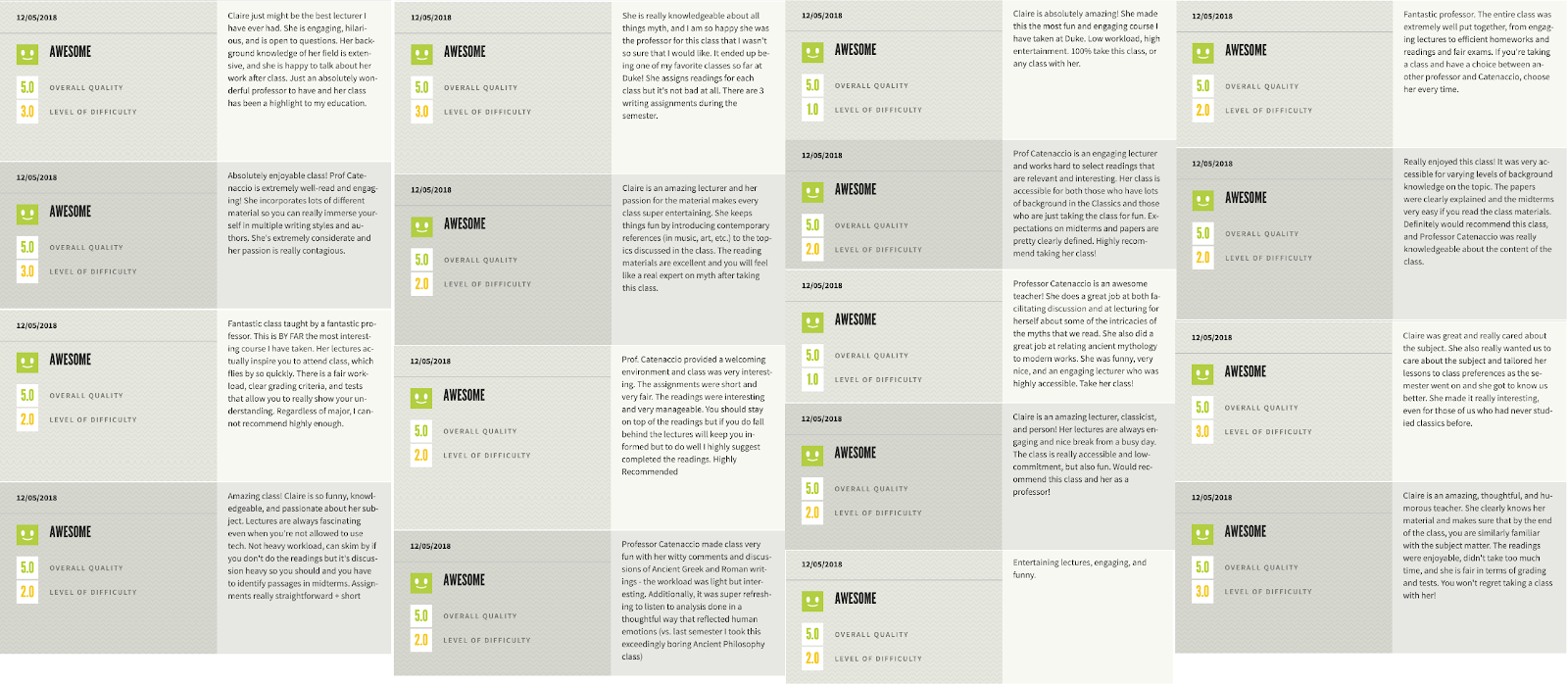

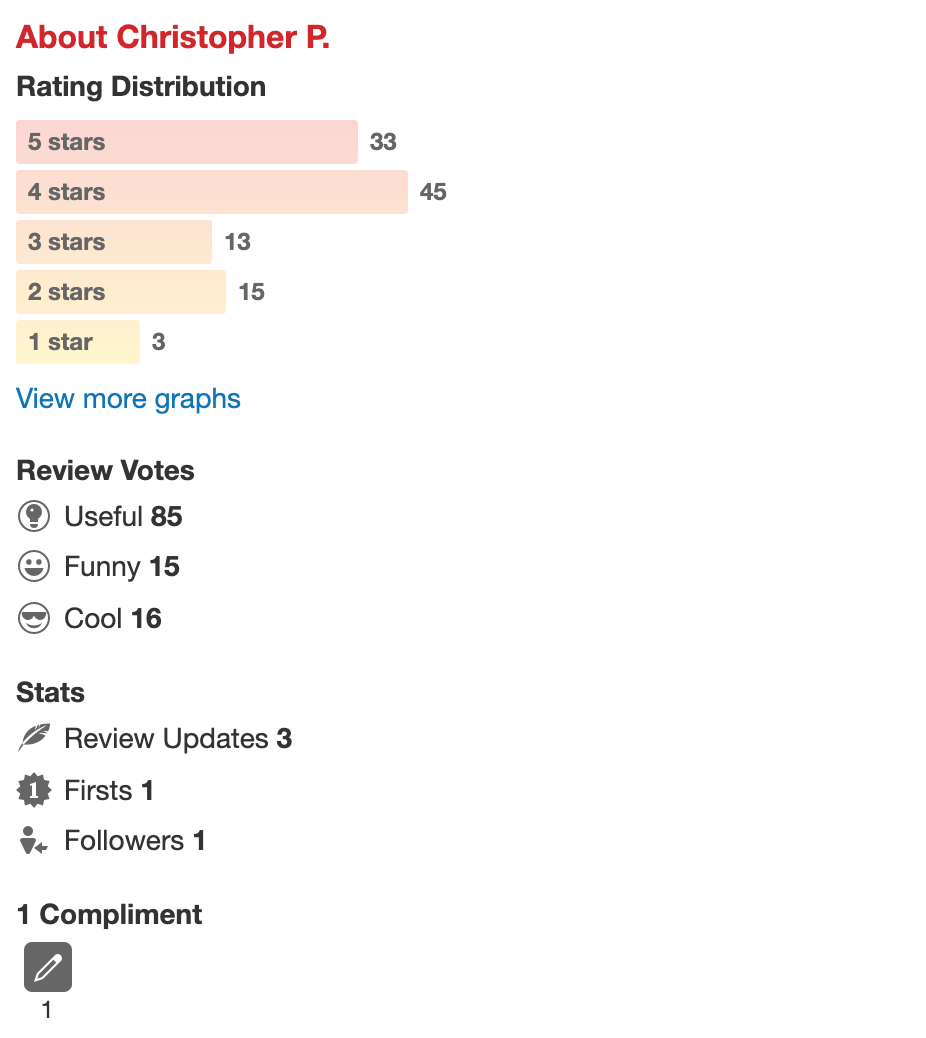

Yelp Stats

Sites whose main function is reviews have taken stronger actions to represent reputation in opinions. Yelp attempts to show a user’s reputation by reflecting the votes others have given on their reviews (as well as some other stats). The advantage of this portrayal of reputation is that it allows users to vet reviewers as ‘legitimate,’ mostly negative or positive in their reviews, or as having tendencies to act a certain way. The main problem with these metrics is that they don’t provide information or expertise; if a user is funny, how does that make them a better reviewer of bars? Sure, if you dig deep enough, you can start to infer certain things like that a reviewer’s past opinions on car mechanics may be strongly supported by the community or that their reviews on hardware stores are thought to be useless. But the search costs for doing this for every reviewer are far too high right now.

Lastly, this representation of reputation doesn’t affect the weighting of stars for a business. You could have a good rep on Yelp and still have the same influence over average ratings as any other user.

Flawed Incentives

Opinions have been recognized for their dollar value on the seller side. As of now, sellers still seem to be the only ones particularly concerned with swaying opinions. The platforms gain from the influx of data, and do everything they can to ensure that this input of data is smooth, regardless of accuracy. They try to remain as objective as possible but still often manipulate results to suit their interests as a company. The buyers have no incentive to review accurately and therefore act based on external interests. Crucially, this whole system is flawed because it functions independently of real monetization for all parties involved.

Nothing at Stake

In the Israeli Army, at the end of bootcamp, soldiers are required to fill out evaluations of the training itself. When members of my battalion filled out this evaluation, my friend told all of us to “write that training was really easy so that the next soldiers have an even harder time!” Because reviews were anonymous and had no built-in reward scheme, there is no incentive to be honest.

A similar situation occurs on college campuses when students are asked to fill out course evaluations at the end of the semester. Because they have nothing at stake and will never take the class again, it is common for them to underplay the difficulty of the class so that future students of the course will have as difficult (if not more) of a time as they did, increasing the value of the previous students’ grades.

So why would people give honest opinions without any incentive?

Right now, as a good actor on Yelp, Google, or Amazon, all you stand to gain for reviewing honestly is a minimal sense of increased reputation. As a bad actor, you lose absolutely nothing for making inaccurate reviews all over the web. This is why we witness 21% more negative reviews than positive ones; with no other incentives involved, anger/frustration seems to be the driving incentive for negative reviews.

The Consequences of Access

As expressed in the introduction, we expect that changes in* access *that occurred as a result of the rise of the internet had a significant effect on the trust in and accuracy of opinions. Access in this case refers to both the ability for anyone to rate products/ services/ content and the ease at which one can see more ratings online.

When online review forums first emerged, they provided increasingly accurate opinions because of the “wisdom of the crowd” effect taking hold. These initial communities were small, and natural reputation effects among members existed because many knew each other by name. As misconceptions about the internet dissipated, trust in these reviews grew because they were in fact more accurate. But as access continued to increase and platforms changed, the natural reputation effects shrunk. This decreased the reputation at stake for each user and allowed for fake reviews to thrive, reducing accuracy significantly. Now, there is still a correlation between accuracy and trust; more accuracy leads to more trust, BUT more trust doesn’t necessarily lead to more accuracy. In fact, the more trust users have in online reviews the more worthwhile they are to fake/manipulate, creating a harmful equilibrium: **more accuracy → more trust → less accuracy → less trust → more accuracy … **

If there was some way to (1) improve the user’s ability to identify inaccuracies, (2) deter the manipulation/misuse of reviews, and (3) correctly weight reviewers’ expertise on certain topics, communities could reach a perfect correlation between changes in trust and accuracy.

Carrots, Sticks, and Scarcity

Strong opinion models should provide major incentives for accurate reviews. If users were rewarded (monetarily or otherwise) for reviewing things, they’d take the time to make better decisions. One way of doing this is by P2P validation, meaning that if other users agree with a user’s opinion, either by upvoting their opinion or by submitting a similar review, that user should get rewarded. This can be (somewhat) accomplished with prediction markets, whereby users bet that a product is good or bad and if a majority of betters agree with them, they earn some profit.

On the opposite side is deterrence; users should be deterred from submitting inaccurate reviews. This could be enacted in a similar fashion, whereby users lose something for giving bad reviews that no one agrees with or supports.

This concept has been attempted in the blockchain/cryptocurrency space with the Token Curated Registries: lists of similar products/content/etc. that are curated by staking cryptocoins. This can be perceived as ‘betting’ that a product will be liked by others and they’ll also vote for it. If others also bet on it, you receive a token reward, if no one does, you lose your stake.

The final important piece here is scarcity: users should have a limited amount of reviews that they can give within a set amount of time. If users stand to gain or lose from their reviews, and they can only give their opinion x times a day, they’re less likely to abuse or waste these reviews.

Weighted Opinions

Because not all opinions are equal, they should have different weights over different subjects. The ratings of users who are repeatedly validated for their opinions on restaurants should matter more in the case of restaurants than other topics. Imagine a review platform that functioned like this: Charlie the chef has a “restaurant score” of 5 and a “jewelry score” of 0.5 (the average user score being 1). His star rating of a restaurant would be 10x more impactful than his review of a jewelry store and 5x more impactful than the average user’s restaurant rating. So when he likes a restaurant, it significantly effects the average rating, but when he dislikes a jewelry store, it barely budges. Like the TCR example mentioned above, Charlie has something at stake: his influence. Instead of risking losing money in hopes of gaining some, he’s risking the weighted impact he has within his expertise in hopes of growing it further.

In a platform where opinions are perfectly weighted and distributed, reviews would be more accurate. Investment in malicious marketing would be deterred. The distortion of customer reviews would be difficult. Cash would flow towards improving product quality + retaining users, rather than used to bolster the fraudulent image of a popular, well-liked company. However, accomplishing this in a fair and peer-to-peer manner is difficult without some decentralized consensus, which we’ll discuss below.

Data Legibility

People often talk about data transparency, but what about data legibility? Even if users have access to enough data on particular products, services, or the reviewers of them, rarely is that information fully comprehensible by the average user. The easier data is to understand and leverage to make better decisions, the more difficult it becomes to manipulate opinions and ratings. To return to the *Yelp stats *example mentioned above, Yelp could easily determine a score for a reviewer in different categories of rating. Reviewers could theoretically be given a high score for their reviews on mechanics while a low score for their reviews on bars, and have this be shown to the users directly from the venue page where the review was. By doing this, sites like Yelp can put more power into the hands of the users with the same data that is currently displayed on them. As author James Bridle says:

Those who cannot perceive the network cannot act effectively within it, and are powerless.

Decentralization

Sometimes the centralization of the platform itself can lead to biases and inaccuracies. Even Consumer Reports, which pays reviewers for their ratings and is considered quite accurate, has been susceptible to biases towards certain companies or industries. By altering distribution, the questions asked in the survey, or the demographic of participants, a platform could significantly alter the results of a report. It seems inevitable that one would at some point when you think about the product they are selling: reputation––sometimes on behalf of the consumer and sometimes not.

So if centralized platforms are inevitably going to have some bias, the next best thing must be a *decentralized* platform that no one owns, right? Well, yes and no. Like the email, permissionless protocols allow for some powerful peer-to-peer interactions, and this type of model could be great for opinion economies and reputation schemes. Some potential benefits of decentralization include:

- Fair weighting of opinions voted on by the community in whole

- A single universal reputation/identity that can be used on all sites without ever disrupting those sites business models (like logging into Tinder with your GMail account without Google collecting/selling any data)

- A native and provably scarce asset to facilitate monetization or prediction markets.

- Immutable record of reviews and reputations.

However, decentralized protocols present their own issues such as bribing, collusion, and tragedy of the commons. For example, if a positive rating is worth more to a marketer than the money lost in achieving that rating on one of these platforms, they’ll surely do it. This is entirely possible considering that users will probably not stake too much on one individual rating, especially if there aren’t that many participants.

Conclusion

We hope that nobody sees an online opinion and immediately assumes it to be a perfect indicator of the truth. We hope that the internet generation can discern real from phony without giving it a second thought, that subconsciously filters out advertisements rather than give them precious brain time. And finally, we hope that a new reputation scheme that is fair and incentivized will emerge to disrupt the status quo.