Originally Published - October 1, 2020

Peer Prediction is an under-appreciated field that offers novel approaches to eliciting honest answers.

Can we build a classroom without a teacher?

We can take for granted an ample supply of eager students, communication tools for them to coordinate with each other, and plenty of engaging material online. There are also plenty of readily-available exercises and exams to quiz oneself, topics to write about, and real-world problems to solve. Many of these resources are also already pre-assembled into courses, so self-motivated students know exactly what they should study and in what cadence they should study it.

What remains, however, is crucially important: How do we grade students without a teacher? This is crucial because, otherwise, how are others supposed to gauge whether or not students actually absorbed the material?

The “teacherless classroom” (e.g. edX) is the canonical setting in which peer prediction is studied. In general, peer prediction asks “How do we grade answers without a rubric, while only using said answers?” In this post, after motivating why we might ask such a question in the first place, we introduce and briefly trace the history of this budding, overlooked academic field. In doing so, we’ll understand why the “teacherless classroom” is representative of a myriad of other settings (e.g. curation, verification, governance) and thus appreciate how and why peer prediction is widely applicable.

Grading with a Teacher

Teachers provide an incentive to produce high-quality work. This is because teachers are sources of ground-truth — they look at our work, they query their knowledge-base to gauge what “correct” or “good” work is, and, on our work, they mark any discrepancies with red ink. As hinted, our work may be compared with objective facts (e.g. “You said 2+2 is 5, but it’s actually 4.”) or subjective beliefs (e.g. “This essay is coherent and well-written.”). Thus, teachers provide a ton of convenience in the sense that, within their jurisdiction, their truths are ground-truth. This affects the incentives governing students — they strive to submit answers, write essays, etc. that are as closely aligned with the given ground-truth as possible. Students partake in teacher-led education because they assume (usually justifiably) that a teacher’s ground-truth aligns with a more universal ground-truth.

Teachers make it easy to query the quality of our work, but there’s a catch — they must be trusted. We implicitly rely on professional certifications to ensure that teachers are deserving of this trust, but, unfortunately, there are plenty of settings in which the analogues of teachers cannot so easily be trusted. This has the important, undesirable effect of making the analogues of students either motivated in an undesirable way or complacent.

Consider a prediction market that guesses the outcome of an election. It eventually needs to query an oracle — the “teacher” querying their objective rubric — to learn what the outcome was. Clearly, traders on all sides of the prediction market have a vested interest in manipulating this oracle. Furthermore, the incentives governing traders may be altered — instead of betting on the outcome of the election, they may instead be betting on the output of an oracle that is independent of the election’s results. This undermines the desired predictive aspects of prediction markets.

Consider a poll where each participant is incentivized to answer subjective questions (e.g. What is your favorite fast-food chain?) via some reward. The pollster has no given subjective rubric with which to grade participants, so there is no way for them to distinguish between honest and dishonest responses. Hence, participants are free to randomly answer questions with arbitrary honesty, because their reward will be independent of their answers.

Grading with Peer Prediction

Peer prediction endeavors to remedy the problem highlighted above; peer prediction mechanisms (or, schemes) incentivize honest, high-quality answers by examining the structure of answers themselves. For example, in the teacherless classroom, students grade each other, and the grades they give one another determine how skilled of a grader each student is. In the polling example, participants’ opinions are used to determine how honest each participant is.

Peer prediction mechanisms accomplish this by using measures of correlation that input answers to questions from participants and outputs scores for participants. These scores determine the quality of each agent’s answers. “In the wild,” these scores may be tied to financial incentives; participants may win or lose money based on the quality of their answers. With scores in hand, determining the “actual answer” to a question is straightforward — we can simply take the answers from the agent with the highest score (i.e. the agent with the highest quality answers).

For example, consider three students (A, B, C) who must grade a fourth student (D) on an assignment. Say A and B each give D a 100% except for student C, who gave student D an 80%. A simple correlation measure may be “You get a 1 if you agreed with the majority and 0 otherwise.” Hence, A and B would get a score of 1 and C would get a score of 0, and D would receive a 100%. Note how similar this scheme is to the well-known SchellingCoin game (many of us are already exposed to peer prediction without even knowing it!).

Peer prediction mechanisms are distinguished from one another by their choice of correlation measure. Hence, the history of peer prediction is a history of increasingly better measures of correlation. By understanding this history, we can understand why one may choose one such peer prediction mechanism over others. Furthermore, the history of peer prediction provides us with concrete examples of how peer prediction mechanisms operate.

A Brief History of Peer Prediction

Single-Task

The canonical breed of peer prediction mechanisms are single-task mechanisms, such as Miller, 2004, and Output Agreement (OA). Here, an answer’s quality is judged from a single question answered by each participant. In Miller, 2004, answers to questions are passed through special functions called scoring rules, that compare one’s answer to already-known value or some aggregation of everyone’s answers. For example, one may be scored the closer their answer is to the median of a set of answers. In OA, participants were scored if their answers agreed with those of a random peer.

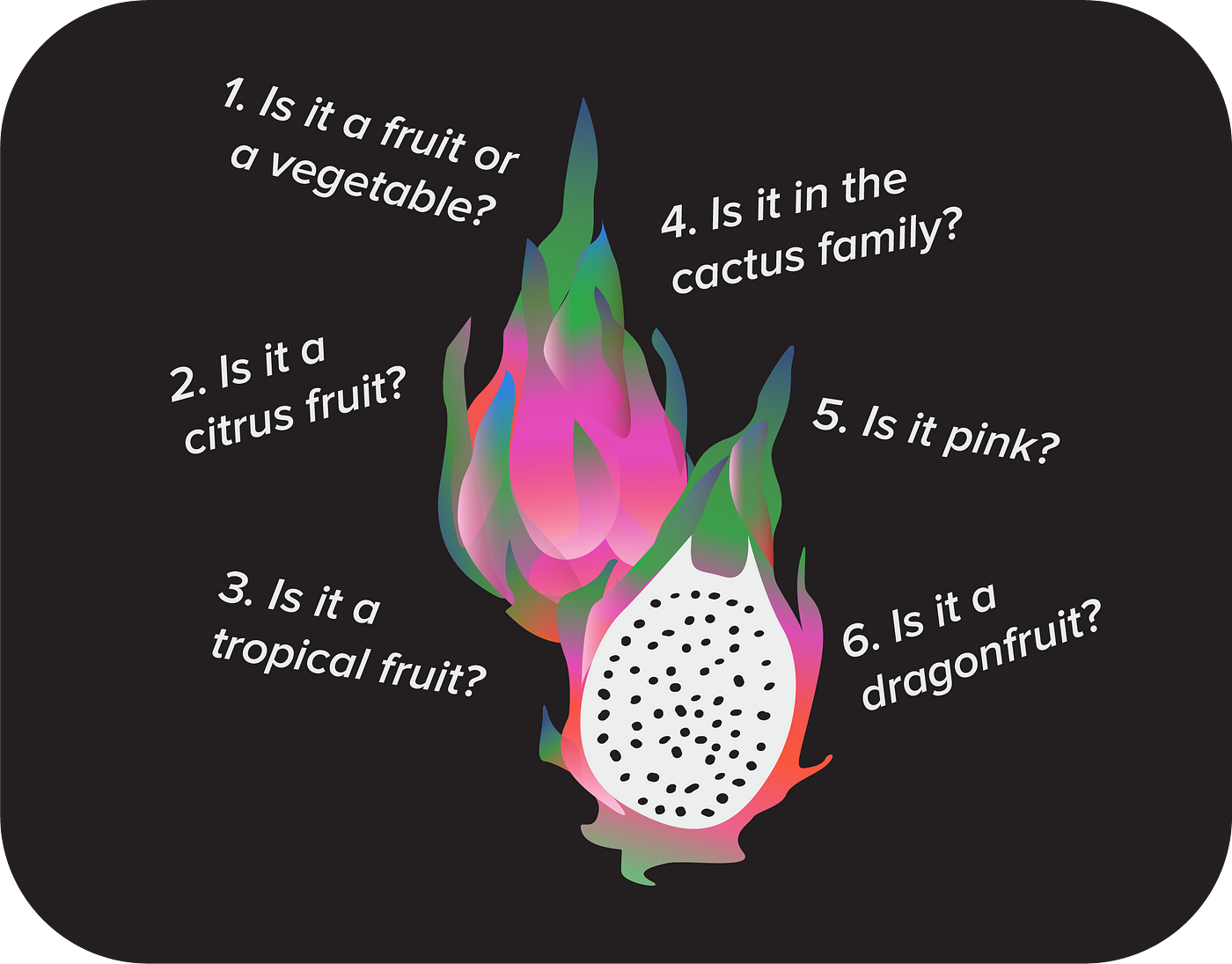

Single-task mechanisms fail to reach a number of desirable properties. In Miller, 2004, it is assumed that each participant has access to a “known common prior,” or, roughly, that everyone already knows what the answer is. To extend our example above, this is analogous to assuming that the median response is known in advance to all participants. Whenever there actually exists a known ground-truth (e.g. for price oracles, who onboard known price data to a different medium) such an assumption isn’t necessarily crippling, but this is not the case for subjective questions (e.g. “Do you like jazz?”), where there may not be a ground truth. In the case of OA, participants are incentivized to state the more general answer rather than the answer that they genuinely believe is true. This is because the more general answer, rather than the “correct” answer, is more likely to be known by a random peer (e.g. Given a picture of a dragon fruit, one is likely to have a higher score by answering “fruit” rather than “dragon fruit” even if one knows for certain that this specific fruit is a dragon fruit because they can’t be sure that others know what a dragon fruit is.).

Non-Minimal Mechanisms

Non-minimal mechanisms are peer prediction mechanisms that ask participants for information beyond the answers themselves. Namely, they ask participants with what probability other people will say the same answer as them, and it is the “least surprised” or “least wrong” or “most predictive” participants that are scored the highest. Such mechanisms include Bayesian Truth Serum and Robust Bayesian Truth Serum.

There are two crucial drawbacks of non-minimal mechanisms that are not exhibited by minimal mechanisms (that only ask participants for answers). First, by definition, non-minimal mechanisms ask for more kinds of information from participants than minimal mechanisms; they presumptuously ask a lot from participants. Second, what they ask of participants is often difficult for people to reason about; people are notoriously bad at thinking about probabilities. These qualities generally make non-minimal mechanisms less attractive than minimal mechanisms.

Multi-Task

Multi-task mechanisms have better fulfilled the promise of peer prediction. They ask multiple questions of participants and thus can better calculate correlations and thus the quality of answers. Multi-task mechanisms have existed since Dasgupta and Ghosh, 2013, and have blossomed into important contributions such as Correlated Agreement (CA) and Correlated Agreement with Heterogeneous Tasks (CAH). A study of these mechanisms shows that these mechanisms work far better and far more often than previous mechanisms.

Despite these successes, multi-task mechanisms may not be practical for sensitive applications. In particular, CA and CAH require infinitely many questions and/or participants to guarantee that answering honestly is always more profitable for participants than answering any other way (e.g. by using a strategy to “game the system” or by complacently answering questions). They are likely to exhibit this property anyway (`1-D *100` percent of the time, answering anything but honestly is no more than `E` more profitable for small, positive `E` and `D`), but this can’t be guaranteed except with an infinite amount of information, which is obviously infeasible.

DMI-Mechanism

This brings us to the present (last year, in fact), with the most advanced peer prediction mechanism to date: Determinant-based Mutual Information Mechanism (DMI-Mechanism). Not only does it ensure that answering honestly is the most profitable strategy, but it does so with a feasible and efficient amount of information; it is the first practical peer prediction mechanism. In particular, it is dominantly truthful for only a constant number of questions and participants.

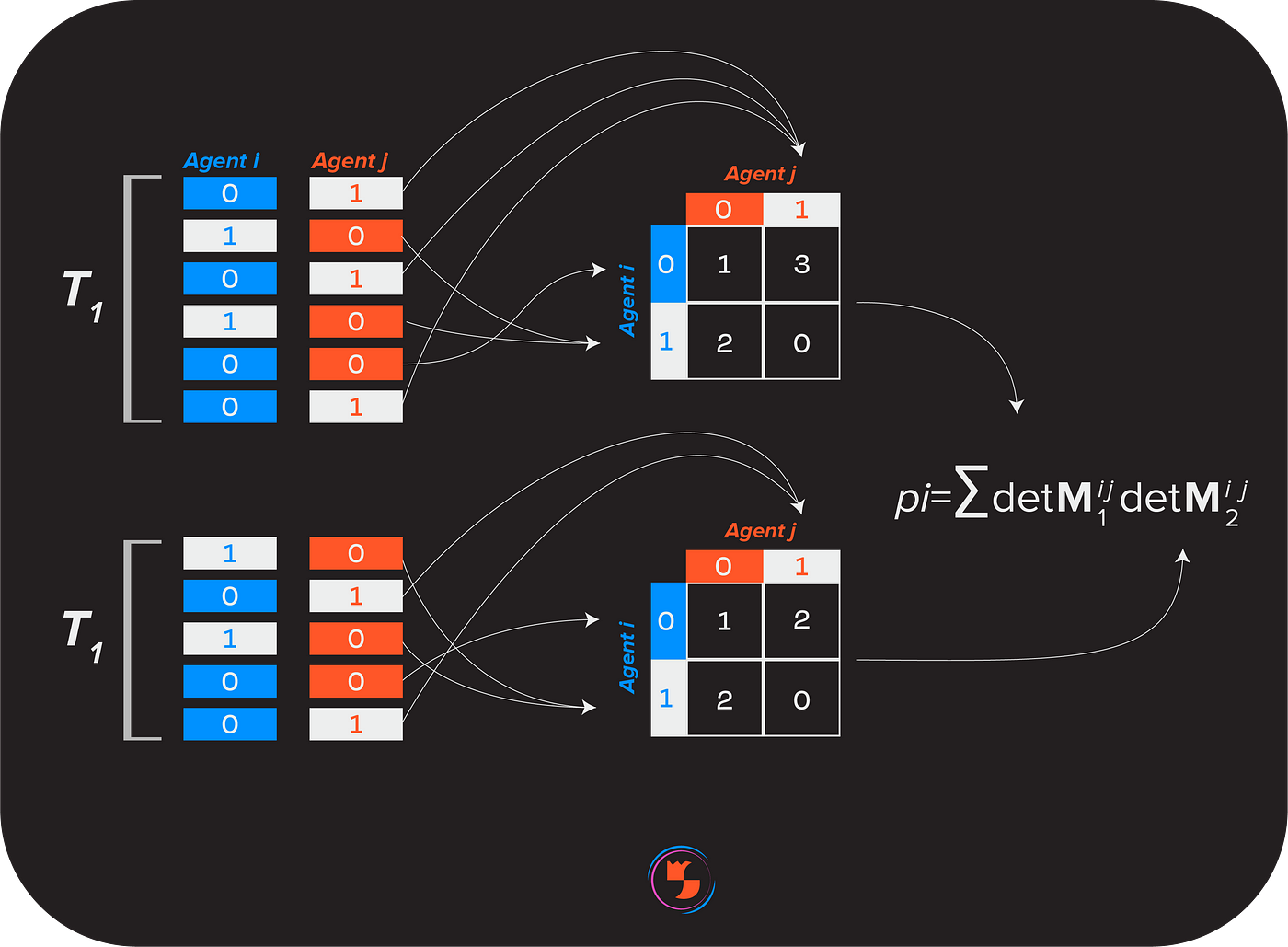

DMI-Mechanism works like this. At least three participants must answer at least 2C questions (where C = the number of possible answers, so a “yes or no” question would have C = 2) for any set of answers to be scored. Participants’ answers are aggregated into columns and are indexed by their respective questions. These columns are paired with one another and then divided in half. Each “pairing of half-columns” is transformed into a matrix that lists the number of overlapping answers between participants. For a “yes-or-no” question, a 2x2 matrix would be formed and entry (1,0) represents the number of times the first paired agent said “yes” whenever the second paired agent said no. The matrix’s determinant is then calculated and multiplied by that of the other matrix.

This product (and thus an agent’s score) is likely nonnegative because if two participants’ answers are negatively correlated, then both matrices are likely to have a nonpositive determinant, so their product is likely to be nonnegative. This product is then calculated for every agent pairing, and the sum of these pairings that include agent X is agent X’s score. This procedure, along with a technical description of DMI-Mechanism and its properties, is given in the paper that introduces DMI-Mechanism.

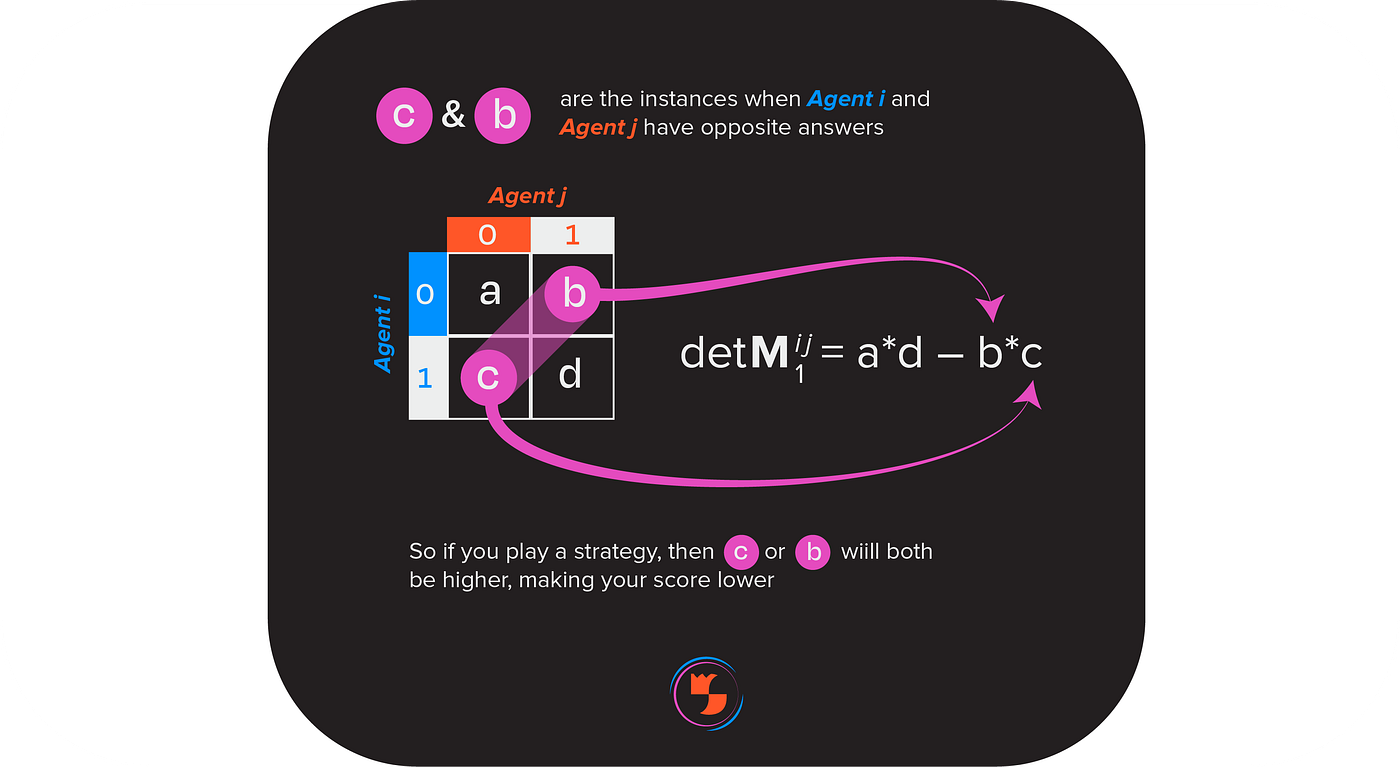

Why does DMI-Mechanism take the determinant of some matrix? The determinant of these matrices detects answering strategies, or any systematic way of answering questions apart from answering honestly. For example, if an ambivalent agent always says “yes” despite the honest answers to some questions being a mix of “yes” and “no,” then, whenever an ambivalent agent is paired with an honest agent, their score will be lower. Both the product of diagonal elements (“a” and “d” in the image below) and the product of off-diagonal elements (“b” and “c”) will be positive, thus lowering the determinant. Hence, the determinant of the matrix, and thus the ambivalent agent’s score, will be less than had they answered honestly.

Applications

As mentioned, the canonical setting for peer prediction is the teacherless classroom. However, there are many other settings that lack an explicit rubric for grading submitted information and thus would benefit from peer prediction.

Verification

Peer prediction could be used to verify the occurrence of an event. The event could be objectively known (i.e. the oracle problem) or be subjectively assessed at the time of verification (e.g. evaluating whether or not a smart contract was hacked could be a subjective matter). Verification via peer prediction can be used to robustly onboarding information on blockchains and to efficiently arbitrate insurance claims.

Prediction

Peer prediction can, as its name suggests, be used to predict future events. Peer prediction mechanisms can distill a crowd’s beliefs into forecasts and thus replace existing methods for anticipating the future (e.g. voting-based schemes and prediction markets). Furthermore, if a peer prediction mechanism is repeatedly applied to the same question (e.g. “Who will win this election?”), one can know, in real-time, the crowd’s beliefs (much like in prediction markets).

Governance

Many voting-based governance schemes arouse voter complacency, especially among large constituencies. This follows from the fact that each vote is not too valuable because its odds of actually influencing an election’s outcome are low. Furthermore, aggregating votes from all voters can be an expensive operation. Peer prediction offers efficient methods of coalescing a crowd’s policy preferences, and an entire constituency does not need to be queried in order to reach a consensus; in the case of DMI-Mechanism, as few as three voters could be queried. Sortition or some other filtering mechanism can be used to select this three-voter committee. This committee’s members may feel empowered knowing that their votes will actually affect change and that they are each incentivized to make high-quality policy decisions.

Peer prediction is an exciting, under-appreciated field with a number of interesting applications. Upshot One is a question & answer protocol that is taking advantage of peer prediction to match questions with high-quality answers.

To learn more about Upshot One, read more of our blogs, read our whitepaper, or reach out to us directly!

Acknowledgments to my co-founder Kenny Peluso for collaboration on this post.