If you lived in England through the mid-seventeenth century, chances are you were slightly—or very—drunk at any given point. Watered-down ale or beer was generally preferred to London’s nasty river water.

Coffee changed that. People were able to think more clearly and stay focused, spurring decades of economic growth. Coffeehouses, in particular, brought people and ideas together, inspiring countless innovations and discoveries. Conversation was the lifeblood.

Businessmen would hang out at Jonathan’s coffeehouse by the Royal Exchange, where the first stocks were traded. Stockbrokers met with merchants, ship captains, and cartographers at Lloyd’s coffeehouse to launch Britain’s insurance industry. Politicians debated at St. James and Westminster. Philosophers and clergy pondered at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Isaac Newton dissected a dolphin on the table of the Grecian Coffeehouse.

Coffeehouses serve as an essential step in the evolution of learning communities.

Realizing Maslov’s hierarchy of needs

So, what exactly is a learning community? At its essence, it’s just a group of people who meet regularly to learn together and collaborate on a shared learning goal.

Besides learning new things, why do people join them? At first, they help satisfy the third level in Maslov’s hierarchy of needs. They help us belong.

But that’s not enough.

People want to belong to a community, and have status within it. They want Esteem, the second level in Maslov’s hierarchy of needs:

Learning communities empower that.

By joining a learning community, you have a clear path towards earning status and recognition. Each member shares a common learning goal and when you make progress towards it, you feel respected. You keep pushing for new breakthroughs.

Learning communities spur innovation.

Bell Labs: a classic learning community

The transistor — billions of which exist in the device you’re reading this post on.

The silicon solar cell — a precursor for all solar-powered devices.

The laser. Communication satellites. Information theory. Unix. C.

All these inventions started at Bell Labs.

What made this place so special? Mervin Kelly, a researcher turned chairman, was most responsible for fueling a culture of creativity.

To encourage a busy exchange of ideas, he needed a critical mass of talented people. At Bell Labs, Kelly housed thinkers and doers under one roof:

Purposefully mixed together on the transistor project were physicists, metallurgists and electrical engineers; side by side were specialists in theory, experimentation and manufacturing. Like an able concert hall conductor, he sought a harmony, and sometimes a tension, between scientific disciplines; between researchers and developers; and between soloists and groups. (source)

It was basically impossible to walk down the (intentionally designed) hallway without running into fellow researchers or developers with interesting problems, diversions, and ideas.

Hate the idea of open spaces at your tech company? You can probably blame Mervin Kelly.

Freedom to explore without overhead was also crucial for research-heavy projects. Kelly rarely checked in on progress until years after he gave his scientists the green light. He would likely scoff at the micro-managing tools we’ve built for project management today.

And most importantly, Kelly trusted people to create and help one another. All employees at Bell Labs were asked to work with their doors open, making collaboration organic and inevitable.

Richard Hamming, a retired Bells Labs scientist, delivered a speech in the mid-1980s to answer the question: “Why do so few scientists make significant contributions and so many are forgotten in the long run?”

I notice that if you have the door to your office closed, you get more work done today and tomorrow, and you are more productive than most.

But 10 years later somehow you don't quite know what problems are worth working on; all the hard work you do is sort of tangential in importance.

He who works with the door open gets all kinds of interruptions, but he also occasionally gets clues as to what the world is and what might be important. (source)

Trailblazing a new paradigm for education

John Dewey, a leading educational theorist in the early 20th century, pioneered this social and experiential approach towards learning.

He believed education stifles individual autonomy when learners are taught that knowledge flows in one direction, from the expert to the learner.

Students thrive when they’re allowed to interact with the curriculum and take part in their own learning. To him, education and learning are fundamentally social and interactive processes.

The purpose of education should not revolve around the acquisition of a predetermined set of skills, but rather the realization of one's full potential and the ability to use those skills for the greater good. (source)

His ideas were met with stiff bureaucratic resistance in public schools. Unfortunately, that hasn’t changed much today.

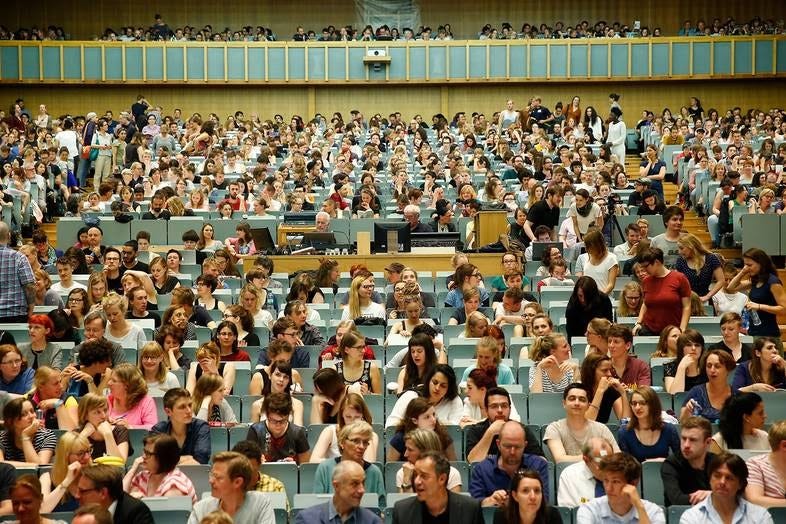

How different would education look if public schools were built around Dewey’s philosophy? For one, we probably wouldn’t be optimizing for grades. And we probably wouldn’t be packing as many students as we could in a room:

Most of online learning faces the same problem. Teachable, Udemy, Thinkific, and others built a new business model by empowering individual educators, but the education itself hasn’t changed from the earliest MOOCs. Learning means pre-recorded lectures or text packaged together in a “course.” This is lonely and ineffective: MOOCs have a 97% dropout rate.

If we flash forward half a century, you’ll see different implementations of student-driven learning communities across many US colleges. There’s an entire textbook covering these experiments.

And guess what? They seem to be working.

Students who participate in learning communities are more likely to persist to graduation (source), feel a strong sense of community and belonging (source), and have improved academic performance.

But these experiments are still quite limited. Take a look at Purdue’s implementation of learning communities. They basically ask a group of students who take the same 2 or 3 courses to live together and hangout. There’s a lot to be desired.

Hello, World!

Welcome to the Internet — the largest, most accessible coffeehouse ever built.

You don’t have to put a group of ambitious people in the same room anymore.

We’re already all here. Hi 👋

Regardless of how “niche” your interest is, there is someone out there who is just as fascinated with that topic. And not just some*one. *Probably a hundred! Maybe thousands!

Take Reddit, for example. You can get brilliant insights in r/AskHistorians, geek out over the future in r/Futurology, or laugh at (and probably get creeped by) muscular kangaroos in r/kangabros.

There’s probably a passionate subreddit, Slack group, Twitter list, or newsletter for almost everything you want to learn.

In my next post, I’ll dive into examples of modern learning communities that bring Dewey’s ideas to life. Whether online or hybrid, free or paid, there are incredible applications in singing, vocational training, entrepreneurship, writing and you know, just having fun.

Afterwards, I’ll write about where we’re headed 🔮

What tools and companies are forming to make it easier to build learning communities? How can founders leverage the scale of technology *— *while retaining intimacy *— *to create new business models?

How can we use the internet to help people find a “sense of belonging” and earn recognition in the pursuit of a learning goal?

Thanks to Foster, Frederic Renken, and Pujaa Rajan for feedback on this post.

Related reading: