Welcome to It Didn’t Happen By Accident, a new series in which we look back at legendary restaurants and the tactics that took them to the top. In honor of the 95th Academy Awards happening this Sunday, writer Darrell Hartman kicks things off by going deep on Romanoff’s – Hollywood’s OG celebrity hot spot. We hope you enjoy, and would love to hear your feedback in the comments below.

Prince Michael Dimitri Alexandrovich Obolensky-Romanoff was about 50 years old when he opened a groundbreaking new restaurant in Beverly Hills in December 1939.

Most of Hollywood suspected that “Prince Mike” Romanoff (aka Harry Gerguson) was not the exiled Russian nobleman he’d long claimed to be, but in a town in which make-believe was the reigning mode, that pesky fact hardly mattered. Romanoff’s well-honed shtick, from his plummy Oxford accent to his weirdly plausible tales of various royal “cousins,” just made him all the more fun to be around. Sure, the dozens of restaurateurs, hotel owners, tailors, and art dealers he’d scammed with bad checks over the years might not agree. But to the movie stars who knew and liked him—many of whom had also reinvented themselves from humble roots—Romanoff was the life of the party, not to mention a surprisingly loyal friend.

A lot of people did not expect Romanoff’s to last long. In fact, it won over the crowds much as its irrepressible owner always had, and sat atop LA’s fickle restaurant scene for two decades. Let’s look at the six factors that made it tick.

A Charismatic (and on-site) Owner

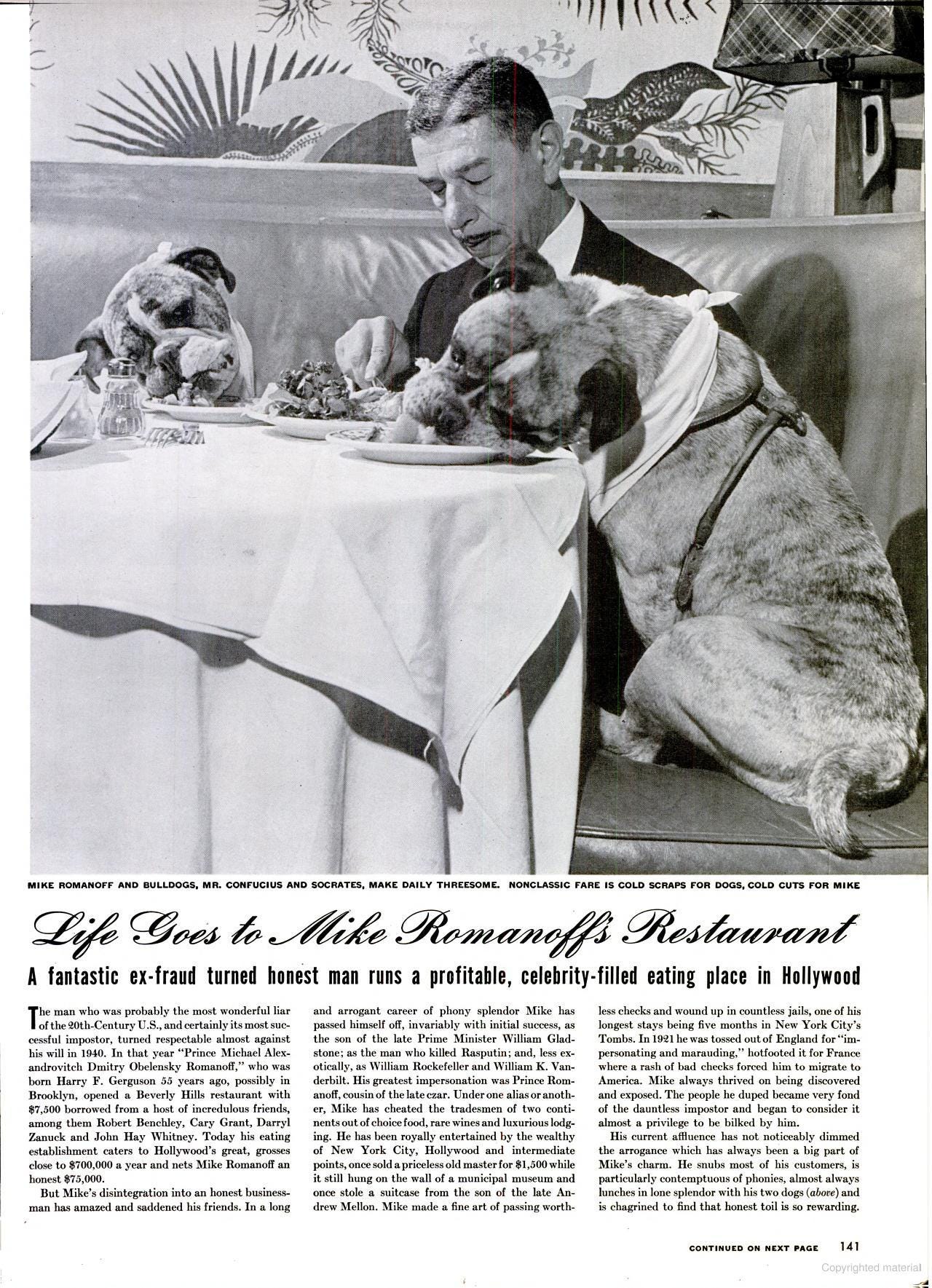

The primary factor was, well, Mike Romanoff, who once declared that a restaurant owner’s personality was its most important element. Obviously, the influence of that personality wanes if that owner is, say, off hosting TV shows and opening branches in Dubai and Las Vegas. Romanoff, by contrast, spent every day in his own dining rooms, running them in imperious and eccentric fashion. He took meals at one of his own tables with his two bulldogs, Socrates and Confucius, eating off plates on either side of him. Unlike other Hollywood restaurateurs, he never kissed up to anyone simply because they were rich or famous; he once turned away the mighty Howard Hughes for showing up without a necktie. Any celebrity who was friends with Romanoff could readily get a table, but otherwise there were no guarantees. Romanoff was discriminating—you might even say he was a snob. But the clique-y, intimate vibe he maintained was also at least somewhat inspired by the former Brooklynite’s deep familiarity with prohibition-era New York City speakeasies.

Serious Star Power

The food at Romanoff’s was nothing special during its first few months in business; when it opened, there were just two menu items. What caused the place to really take off was its insane concentration of star wattage. His friends Cary Grant, Charlie Chaplin, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, and mega-producer Daryl Zanuck were among the original investors—and thus had additional reason to go spend money there. Romanoff's "royal" notoriety had earned him small movie roles; that and the stage presence he exuded in real life helps explain his abundance of famous friends. On the rare occasions when Romanoff relaxed his rule against taking photographs, the results were staggering. A 1945 spread in Life magazine shows a crazy number of A-listers having lunch there, and several of the most iconic candid images of Old Hollywood emerged from private events at Romanoff’s. Among them are this one of Sophia Loren giving rival sex bomb Jayne Mansfield the side-eye and Slim Aarons’ famous “Four Kings of Hollywood” photo of Clark Gable, Jimmy Stewart, Gary Cooper, and Van Heflin at a white-tie New Year’s Eve party. The publicity value of this A-list crowd was priceless.

A Brutally Hierarchical Seating System

Between its two dining rooms and sun-dappled patio, the original Romanoff’s on North Rodeo Drive seated 150 people. For Hollywood bigwigs, though, the only seats that mattered were the five booths in the front room, which were in plain view of everyone. Movie stars would linger for hours at the bar in hopes of securing one, while the pleasant back room was considered Siberia. Whether this cruel imbalance was a feature or a bug of Romanoff’s success is hard to say. Romanoff himself found the drama it caused annoying, and when he reopened at a new location in 1951 he scrapped the setup. The main room of the second Romanoff’s, though larger, actually fit fewer people, because it consisted entirely of banquettes, all of which had good sight lines. “There is no use having tables people don’t want to sit at,” Romanoff explained. He made it impossible for diners to avoid the spotlight, and he seated the most famous ones in a different area each time they came in, so that no one part of the room became more desirable than any other.

A Top-Flight Menu

The food at Romanoff’s quickly hit its stride, thanks to French chef François Pallares, whose enduring contribution to gastronomic history is chicken Romanoff (cold boiled chicken breast, diced and simmered in sherry, with cream sauce and sprinkled with dark cherries). Another popular Pallares invention was the Omelette Sylvia, made with chicken hash and smothered in cream. Though Romanoff himself disdained fresh greens and told dieting movie stars to go elsewhere, his kitchen turned out an excellent Green Goddess salad. Hollywood enjoyed dessert much more in those days; Gregory Peck had a weakness for Romanoff’s banana shortcake, and the restaurant’s individual-sized chocolate soufflés (a novelty at the time) were a huge crowd-pleaser. Romanoff’s also maintained its “royal” image by staying extravagantly well supplied with premium caviar and ice-cold Dom Perignon. There was no better place to court a potential client or celebrate a two-picture deal.

Airtight Books

Even if the ex-charlatan Mike Romanoff had “disintegrated into an honest businessman,” as one magazine quipped, tracking incoming and outgoing cash had never been his strong suit. The unsung hero of his lucrative restaurant business was one Gloria Lister, who came on as bookkeeper in 1945. When she resigned in 1947 to take a secretarial job in Palm Beach, Romanoff flew to Florida to win her back, and not just for business reasons. One year later, Gloria became his wife. When the new Romanoff’s opened on South Rodeo Drive—this time in a building that it owned, eliminating previous landlord problems—she began capably managing the day-to-day operations of the larger enterprise, which included a ballroom and several private dining rooms. Romanoff’s developed its share of problems by the late fifties, but the back-of-house was not one of them.

Only in L.A.

The Romanoff’s magic worked especially well in Los Angeles, and maybe only there. Outposts in San Francisco and Palm Springs were short-lived. Whenever Romanoff temporarily lost sight of which town he was in, he paid the price. At the request of two powerful producer friends, he agreed to put Republican literature on his dining tables—during a time when Republican Senator Joe McCarthy was harassing some of Hollywood’s brightest talents for alleged Communist sympathies. It was a foolish decision, and one that lost him the goodwill of many regulars.

Romanoff had certainly earned the right to take time off by the late fifties, as he approached age 70, and he did just that, traveling the world as part of his pal Frank Sinatra’s entourage. But his long absences from the restaurant—along with changing fashions and the fadeout of Old Hollywood—hastened its decline. He closed for good in 1962. The story of his life has been optioned more than once over the years, but has never been told on screen.

Darrell Hartman is the author of Battle of Ink and Ice: A Sensational Story of News Barons, North Pole Explorers, and The Making of Modern Media (Viking, 2023). His writing on history and other subjects has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Condé Nast Traveler, The Daily Beast, The Paris Review, and elsewhere. Follow Darrell on Twitter and Instagram.