The Merge moved Ethereum from PoW and PoS, and Bitcoin maxis are losing it!

Last week, after months and years of waiting, the highly anticipated Merge finally took place, transitioning Ethereum from the energy-intensive Proof of Work consensus model to its GPU-friendly Proof of Stake alternative. While the community celebrated this historic and long-awaited upgrade, Ethereum’s detractors were not long in starting their latest assault, this time claiming that running on PoS has made Ethereum more centralized.

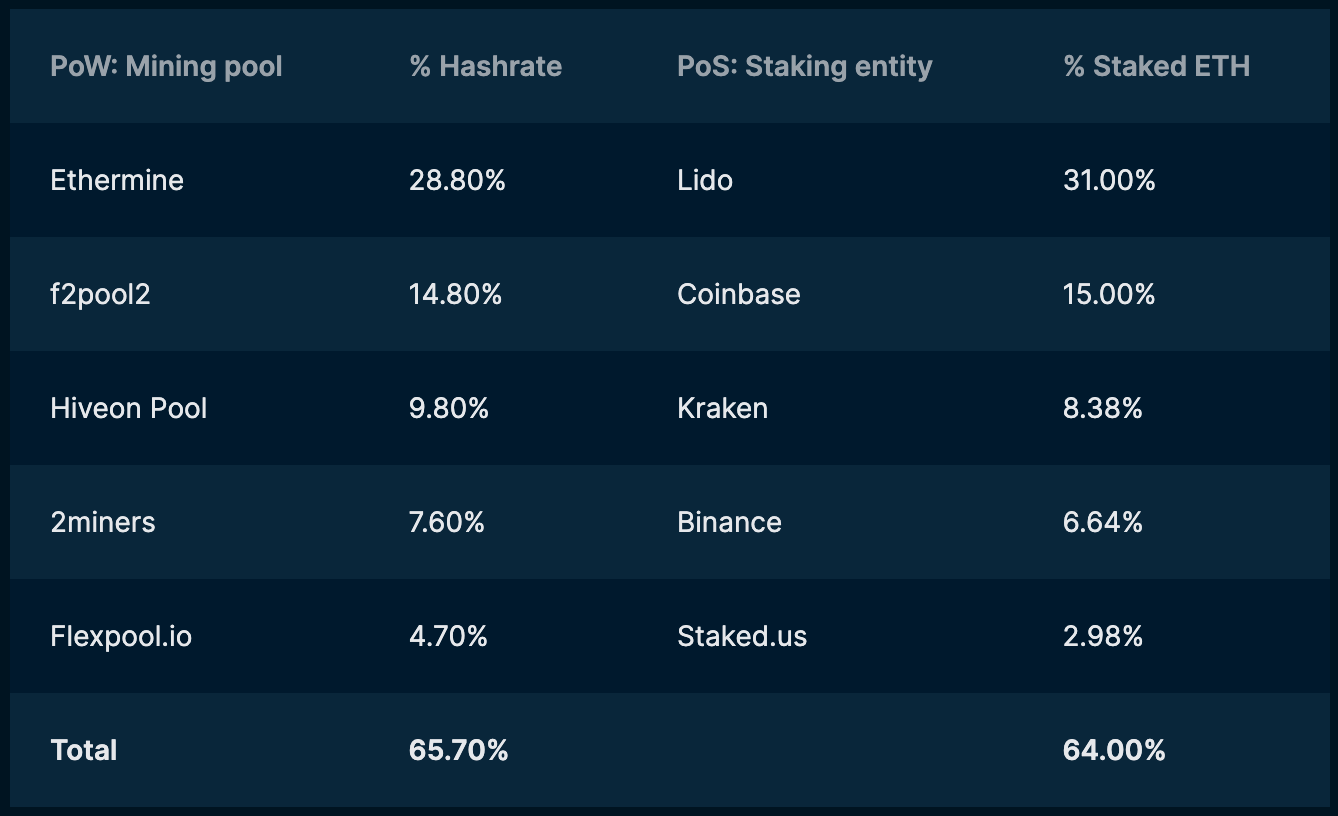

Led mostly by miners and a drove of holier-than-thou Bitcoin maxis, these folks saw that a 5 entities have around 65% of staked ETH and were quick to pronounce that Ethereum is now more centralized than ever.

Is there any truth to their argument or is this the usual hue and cry made whenever any blockchain takes a step away from antiquity? Let’s break it down.

Stakers vs Validators: Understanding Ethereum PoS

A lot of this debate about Ethereum’s apparent centralization stems from not knowing the fundamentals of how PoS works on the network. So let’s clear up some basics.

First off, to be a validator on Ethereum, you need to stake 32 ETH. Staking more than that amount will not earn you more rewards, because each validator is limited to an effective balance of 32 ETH.

Secondly, there are 4 types of staking on Ethereum:

-

Solo staking: You run your own hardware and stake 32 ETH to become a validator.

-

Staking as a service: You stake 32 ETH but pay someone else to run the hardware.

-

Pooled Staking: You stake less than 32 ETH in a validator pool. Some pools provide you with an ERC-20 liquidity token (which can be used on the network) to represent your staked ETH.

-

Centralized Exchanges: You stake less than 32 ETH with a centralized exchange, which requires the least amount of effort.

Now that we have that cleared up, let’s come back to the argument. The fact that 5 entities control a majority of staked ether might be concerning at first glance, especially since 3 of these entities are the centralized exchanges Coinbase (14.6%), Kraken (8.3%) and Binance (6.6%). The largest share, however, is under Lido, which has deposited ~30% of the total staked ether.

It’s important to note that all these entities are not single validators, but operators of validator sets.

Lido, for instance, has over 128k individual validators under it, while Coinbase has just over 59k. Allowing centralized exchanges to consolidate large pools of ETH and run numerous validators is certainly risky, especially if you consider an external attack as the biggest threat. But the risk is offset to an extent by Lido.

Lido offers pooled staking services governed by the Lido DAO, which is managed through ownership of LDO tokens. If one wallet managed to get a majority of the total supply of these tokens, it’s possible that they could exert unilateral control over Lido’s validator set. But that risk is present in all decentralized protocols managed by a DAO. For now, however, Lido serves to mitigate the risk posed by the CEXs making up the group of ETH stakers.

If we imagine that Lido, like the CEXs, has full control over its validator sets, there is another question: why would they become bad actors?

Little to gain and a lot to lose

Ethereum has provisions in place to punish validators acting in bad faith and has implemented mechanisms which make it harder for bad actors to gain control over the network.

Ethereum randomly selects validators random to build and propose blocks, and validator committees to attest these blocks. Any validator who fails to perform these duties when called upon is subject to incurring a financial penalty. Validators who commit more serious transgressions, like proposing two different blocks for the same slot or attesting two proposers for the same block, face the more serious punishment of getting slashed.

When a validator is slashed, 1/32 of their staked ether (up to a maximum of 1 ether) is immediately burned, then a 36 day removal period begins, during which the stake gradually bleeds away. At the mid-point (Day 18) an additional penalty is applied whose magnitude scales with the total staked ether of all slashed validators in the 36 days prior to slashing event. This means that when more validators are slashed, the magnitude of the slash increases. So if there are lots of validators being slashed, they could lose their entire stake). And remember that validators receive far lesser ETH in block rewards than miners did.

This alone should disincentivize operators of validator sets from attempting to game the system either for personal gain or to comply with censorship-happy regulations. But what about a 51% attack you ask? Yes, that risk still exists, just as it did with PoW, but PoS enables the community to fight back!

In PoW Ethereum, an attacker seeking to gain control over the network needed to control 51% of the blockchain’s total computing power, which amounted to billions in equipment and energy. In PoS Ethereum, an attacker would need 51% of the total staked ether (~13,773,610 ETH), amounting to over $9 billion.

Suppose that an attacker managed to control this much staked ETH and used their own attestations to fork Ethereum. What then? Well, honest validators could continue building on the minority chain, which would eventually become the canonical chain since all nodes, dApps, exchanges and other protocols would rather run on a secure chain rather than an insecure one. A more drastic, and perhaps more fitting, counter-attack would be to just kick the attacker from the network and destroy all their staked ETH!

Proof of Stake, on Ethereum at least, is more crypto-economically secure that Proof of Work.

There’s another reason why a staking entity would not be keen to try an attack Ethereum: it would destroy their business! For instance, if Binance attempted something stupid like using all the ETH their customers staked with them to manipulate Ethereum, they would:

-

Lose all the money

-

Get rekt by countless lawsuits from their rightly pissed off customers

-

Dissolve into oblivion while their competitors divvy up their business

So, economically speaking, a staking entity acting maliciously on the Ethereum network has nothing to gain and everything to lose.

But I’m sure there are some Bitcoin maxis or disgruntled former miners who are railing about the possibility of a single entity with a large enough stake gaining unilateral voting power. I’d like to remind anyone in this camp that Ethereum doesn’t have on-chain governance. Any changes to the network and its operation are decided off-chain, through Ethereum Improvement Proposals (EIPs).

Ethereum’s validators can’t vote to enforce protocol changes, regardless of how much ETH they have staked

All the noise coming from the anti-Ethereum camp after the Merge led me to consider another thing…

Is Ethereum’s centralization really the issue?

But never mind that, let’s just stick to the blockchain stuff. These detractors act as though PoW was the ideal consensus mechanism, one with no security vulnerabilities or concerns of centralization.

Those who are berating Ethereum PoS for violating the core principle of decentralization seem to forget that the landscape was not so different under the PoW mechanism.

Mining has extremely high resource requirements in terms of computing hardware and electricity costs. A typical Ethereum mining rig needed 8–16gb of RAM and a purpose-built motherboard that could support up to 14 GPUs. For a solo miner in a country with high energy prices, the mining rewards wouldn’t offset the amount spent on hardware and electricity. Only the richest entities could participate as standalone miners.

So, just as how there are staking pools now, there were mining pools before, with most of the network’s hashing power concentrated in the hands of a few entities.

True, there are no CEXs on this list. But there were other problems: like the proliferation of front-running bots who made profits by incentivizing the MEV-hungry miners.

The people decrying the supposed centralization of Ethereum may be the loudest, but that doesn’t mean they’re the only ones with hot takes about why the network is failing.

From SmartFi executive Chris Terry stating that “…the Ethereum blockchain is subject to ‘transaction censorship”, to Max Gagliardi comparing ETH to fiat currencies because “Proof-of-stake has no connection to the physical world or energy required to create the new currency.” By the way, Mr Gagliardi runs an oil-and-gas infrastructure company and a Bitcoin mining firm (both called Ancova). So you can see why he’s a little miffed about progress being made on the energy front.

Then there are others who rip into Ethereum in order to shill what they think is the best blockchain network. Like Dr Craig Wright — who’s farcically claiming to be Satoshi Nakamoto — saying that Bitcoin Satoshi Vision is going to ultimately absorb Ethereum’s operations, and Steven Stadbrooke, who derides Ethereum merge as a rich-get-richer scheme and claims that “Ethereum is as useless as a glass hammer” so the drastically reduced energy consumption post-merge is still a waste!

It’s clear then that many of these Ethereum detractors are not driven by worries of centralization, but either by the fear of losing their revenue streams or by the promise of unrealized future gains.

But if they go around proclaiming that Ethereum is useless and BSV is the best blockchain, then there really is no discussion to be had. It’s like talking astronomy with someone who thinks the moon is made of cheese.

What makes a blockchain decentralized?

A blockchain’s decentralization isn’t just a measure of how diverse its consensus keepers (miners and validators) are. That is surely a factor, because a blockchain with 300k unique validators is inherently more secure than one with just 300 unique validators.

But one must also take into account the number and diversity of nodes keeping the network running, because they’re the ones who regulate the flow of information in and out of the system, and they’re the ones who ‘watch the watchers’.

Ethereum’s move to PoS wasn’t just to reduce energy use. It is the first step in a multi-year plan which aims to solve the blockchain trilemma of decentralization, scalability, and security. Here are the changes we can expect to see in Ethereum in the coming years:

-

ETH becomes a deflationary currency as burn exceeds issuance

-

The introduction of Sharding in the Surge will increase the network’s throughput, and the elimination of old state and history in the Purge will make it easier for people to run nodes by lowering resource requirements to do so.

-

The implementation of Proposer Builder Separation (PBS) will change how validators function and will make it even more difficult for them to misbehave.

In conclusion, Ethereum does face the possibility of having to deal with centralized entities managing consensus in the future, but the situation today is nowhere near as grave as those BTC-adherents would have you believe. They’re just cranky because their favourite asset is at risk of being flipped by one that’s more practical and environment-friendly.

For a comprehensive takedown of the dumbest arguments against Ethereum, read this newsletter by Bankless: 15 Bad takes on Ethereum

If you liked this article, follow the roverX Medium publication for the latest insights on the world of Ethereum.

If you’re an NFT trader looking to up your game, drop us a follow on Twitter for project analytics or join our community on Discord.