The pricing of digital assets is different but not entirely difficult

Pricing, in general, is such an interesting topic and almost an art to get right. On one hand, if one prices too low, one may miss out on potential revenue. On the other hand, if one prices too high, people may not want to buy.

In our physical world, it’s relatively easy to price and adjust pricing based on customer reception. Perhaps, a company has come out with a new product. It’s relatively easy to survey potential customers and/or have the product sell in a smaller market before launching more broadly.

Even after a product is launched to a larger market, it’s still relatively easy to adjust pricing in the way of sales to get inventory moved.

With digital assets, the situation is a little different.

Transactions are transparently recorded, such that it’s possible to know who received what at what price. Discounts, though possible, become a little difficult with collectors buying in at a higher price potentially feeling deluded.

Moreover, many NFTs are driven by hype. So much of the success of a given NFT is weighted on the front end of the entire lifecycle of a token.

Even if repricing can happen, it’s often too little too late to make an impact on the masses, as many will have already moved on.

What’s someone selling NFTs to do?

There are a number of strategies that can help a one gravitate towards a good price. Price doesn’t exist in isolation though. A “good” price becomes less “good” the more supply there is, for instance.

As a result, it’s useful to consider factors that impact whether or not people will want the NFT one is selling in the first place. Some factors, though not exhaustive, include:

-

Notoriety

-

Perceived Complexity

-

Variability

-

Edition Size

-

Market Size

-

Memeability

-

Utility

Notoriety

Perhaps not surprising, the more notable the project owner is, the more demand there will be for their NFTs. This notoriety is compounded by previous success and the amount of time since this last success (with shorter spans having more strength).

In the Tezos ecosystem, for instance, anything that Zancan touches might as well turn to gold. His NFTs are in high demand due to the prestige associated with him and his art.

Perceived Complexity

This applies more to art-based NFTs, but a token is going to be more valued if it appears to be more complex versus what is out there. AI art sometimes runs into this issue with AI art being seen as less complicated to produce than say a hand-drawn, impressionist landscape.

Variability

Collectors like when their tokens look unique. The more distinct a piece looks in a collection (while maintaining cohesion), the more valued it’s going to be.

This point comes up a lot in generative art collections where a piece may have a sufficiently good starting price and edition size, but the pieces the themselves aren’t very distinct from each other. When pieces largely start looking similar, it may be better to consider a smaller collection size.

Edition Size

Simply put, the more tokens that are out there, the lower price one can expect.

Market Size

Large markets with low supply are ideal for realizing higher profits. Though a niche like Goblincore may be charming, for instance, the entire market size isn’t that large. It may be easier to curate an engaged audience, as a result, but it also becomes easier to run into issues around market saturation.

Especially in a low market, it’s important to consider that the number of potential collectors may be smaller than what previously existed.

Memeability

So much of the Internet runs on memes. The ability for a collection to become a meme increases the likelihood that it will both become a meme and spread as a result of memeing.

Utility

Most of the utility of NFTs comes from the visual aspect. Art NFTs are especially mostly appreciated, but a few tokens do come with other perks. A token with additional utility beyond mere appreciation will often have a positive impact on desirability.

Pricing Strategies

With the above variables that impact pricing in mind, here are some strategies that can help one land at a great price:

-

Allow Offers

-

Using Comps

-

True Dutch Auction

-

Tiered Dutch Auction

-

English Auction

-

Offer Triggering Auction

Allow Offers

If one doesn’t know what to price a digital collectible, probably the simplest way of figuring out a price is not really figuring a price at all. Essentially, one allows the collector to figure out the right price.

This method works well if the widest audience knows that any given token is available for offers. Often, one should also give additional parameters related to accepting an offer.

Perhaps one accepts the first offer. Perhaps, offers are collected for 24 hours after the first offer is made with the highest offer winning. Providing transparency around how an offer is accepted will engender trust in future sales.

Using Comps

Probably one of the most common strategies is using comparables to land at a good price.

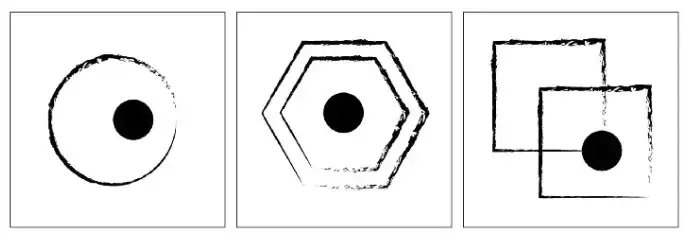

To do this, consider the NFT, what it looks like, what it does, etc. Find tokens that have been sold that are comparable in nature:

-

Similar aesthetic

-

Recently sold

-

Similar artist popularity

-

Similar amount of difficulty in producing

-

Similar utility

Sometimes, this might even consist of looking within an already developing collection or breadth of work.

Assuming the other two sold today, these are good comparables.

Same assumptions, these comparables aren’t as good.

Take these sales numbers and use them, along with the pricing factors above, to come to a suitable price.

Perhaps this means slightly discounting a piece from an average sale price of 0.1 Ξ if one is a new artist. Perhaps this means slightly decreasing the price because the art, though sophisticated, might be perceived as easier to create.

Good comparables, overall, are ones that are timely and closely-related to what is being compared. The more recent and similar a token is to something that has been sold, the better.

Dutch Auction

In this format, a price starts high and incrementally go down to zero until a buyer steps in. To get the most out of this pricing strategy, it helps to start at a price that is almost ridiculously high. This allows for market discovery.

Many dutch auctions will start lower, but any price that starts below what people might be willing to pay neglects potential value that could be earned.

Dutch Auctions work well if there are fewer pieces to look at, at a time. Especially if multiple Dutch auctions are started and slated to end at the same time, it can be a nightmare for collectors to figure out what auction to pay attention to.

Tiered Dutch Auction

This format is similar to a Dutch auction with the caveat that increments are tiered and reached after fixed amounts of time.

Because tiers have to be chosen, it’s like arriving at “good” price for as many tiers as there are. This method is somewhat arbitrary compared to the Dutch auction, though it does provide some room for price discovery.

If a tier is slightly higher than what people want to buy in at, then the lower tier will be where things get settled. The delta between the desired buy-in level and the next tier is potential value that is lost.

English Auction

This is the standard auction that people tend to think about. Bids start at some base point and go up until there are no more bids to be made. English auctions allow the price to get to the true price that collectors are willing to pay at that given point in time.

Some of these auctions have a finishing time. The finishing time can sometime get in the way of value capture in the sense that interested buyers have to be around during the ending few minutes of an auction to make sure that they secure the NFT at the price they’re willing to pay.

If there is a mismatch between those willing to pay more and that time that they are around, there will be a loss in potential value captured.

Offer Triggering Auction

I first encountered this model through gengoya about a year ago. The process goes as follows:

-

Announce piece and mint

-

Allow offers

-

Once an offer is placed, reach out to highest offerer

-

Schedule auction based on offerer preference

-

If an auction resulted in no activity, the offerer would get the piece at their offer price

Oftentimes, the total length of these auctions would be on the shorter side (6 to 12 hours) and end during a timeframe that the offerer would be readily available. This method was interesting as it helped boost the minimum starting bid and meant that there was always going to be a ready buyer.

A note about minimums and reserves: if these numbers are too high, any kind of bids or sales that might otherwise happen, won’t. Using minimums or reserves can be a good way of priming price to move a certain way,

On timing: any auction can realize a good price at the time, but they can be made better by broadening knowledge of the auction.

As more protocols and artists come about, I’m sure many more strategies will surface.

If this article was useful, you might want to take a look at Why Your NFT May Not Sell and my two part post on How to Sell More NFTs as an Artist.

If you’ve enjoyed this, feel free to follow me @cryptomoogle. As always, let me know your thoughts!