This article was originally published on Substack on February 16, 2021. It is released here under the notion that all Ethereum protocol research should be free and accessible.

TLDR;

The fixed income analogy used to model staking cash flows, or issuance in flows models, is flawed. New issuance is internal, available to all token holders, nearly without cost, and has a low barrier to entry. As a result, proof-of-stake demonstrates a much smaller Cantillon Effect compared to proof-of-work.

Rather than analyzing staking rewards in an inflationary environment (before token burning), one should recognize that staked ether are guaranteed to be deflationary and to increase the staker’s share of the token supply. With all the deflationary effects combined, staked ether tokens will initially see a total ether supply deflation rate in the low-teens.

Author’s Note

The objective of this writing isn’t to discuss whether the Cantillon Effect is a real phenomenon, but instead to use it as a starting point and framework to discuss different forms of inflationary dynamics and why some can be more problematic than others.

Estimated reading time: 14 minutes

The Cantillon Effect

The popular belief summarizing the Cantillon Effect is that the closer you are to the money printing process, the more you benefit from inflation or monetary debasement. Essentially, it’s a chain where the beneficiaries of recent monetary policy are ordered as follows:

government > high net worth individuals > middle class > low income;

or more precisely,

recipients of money > owners of hard assets > debasable assets > no assets.

Matt Stoller and Sahil Bloom have both written better and more in-depth descriptions of the Cantillon Effect than I am capable of providing, so if this is a new concept to you and you want a deeper modern breakdown, I would direct you to them.

In reference to the Coronavirus stimulus, Stoller asks:

Why is the money meant for everyone only showing up in the stock market?

And in a data driven piece, Bloom analyses the difference between the Federal Reserve’s asset purchase program and the government’s direct stimulus checks. He provides insight into why:

Inflation is running hot in the U.S. But perhaps more importantly, [why] it's also running disproportionately hot.

Jumping back in time to the source material, Richard Cantillon wrote:

Par quelques mains que l’argent qui est introduit passe, il augmentera naturellement la consommation ; mais cette consommation sera plus ou moins grande suivant les cas ; elle tombera plus ou moins sur certaines espèces de denrées ou de marchandises, suivant le génie de ceux qui acquièrent l’argent.

Richard Cantillon - Essai sur la nature du commerce en général (1755)

My translation of that statement is:

When new money is introduced to a system, it causes a natural increase in consumption, but this consumption is biased towards the preferred commodities and goods of the recipients of the new money.

*Special thanks to @profchaine on Twitter for a brief consult on the translation.

The original text focuses on the distortion of local economies with the discovery of new gold mines and the effect of wealthy shipping merchants arriving at foreign ports, but with small adjustments we can bring the theory forward in time. The modern implication of the passage is that financially savvy investors can respond to quantitative easing by positioning themselves early in the path of the flow of money—leading to excess rewards for the wealthy and to perpetually growing wealth inequality.

Essentially, the problem with new money entering an otherwise closed system is twofold:

- The new money tends to be introduced/distributed unequally;

- prices are distorted unevenly depending on the distribution of the new money.

If the introduction of new money results in either of those two issues, then the ensuing inflation is problematic.

It’s worth noting that the Cantillon Effect has been largely misappropriated to simply suggest that inflation is bad and that hard money is the solution to wealth inequality. Pointed out by the American Institute for Economic Research:

It is ironic that the monetary-redistribution analysis that so endeared [Cantillon] to Austrians is based entirely on a gold standard.

Joakim Book - *The Mythology of Cantillon Effects (*2019)

The solution to reducing the Cantillon Effect and problematic inflation is not simply hard money. To prevent the distortion of pricing and the rise of wealth inequality, new money must also be efficiently distributed. If there is excess money to be made in the generation of new hard-money (e.g, gold mining generating more revenue than the cost of extraction), then there is what I’ll define as a Cantillon profit*.* These Cantillon profits allow the government, large corporations, and other robber barons to make nearly risk-free fortunes while everyone else suffers the consequences.

Bitcoin and Proof-of-Work

Swapping into the cryptocurrency realm, bitcoin is often touted as a solution to the Cantillon properties of fiat because of the protocol’s strictly defined and immutable disinflationary issuance schedule. Satoshi’s precognition of increasing computational power, and the inclusion of a difficulty adjustment to prevent above-target inflation is without a doubt a foundational breakthrough.

Although bitcoin is a vast improvement over fiat currency, it is not flawless in its inflationary design. Fitting with its moniker of ‘digital gold’, the process of bitcoin mining is dilutive to the already minted supply of coins, while being distributed unevenly and subject to large Cantillon profits. The high costs associated with participating in the modern mining ecosystem and the favorable margins for miners who gain access to cheap electricity create a compounding wealth effect.

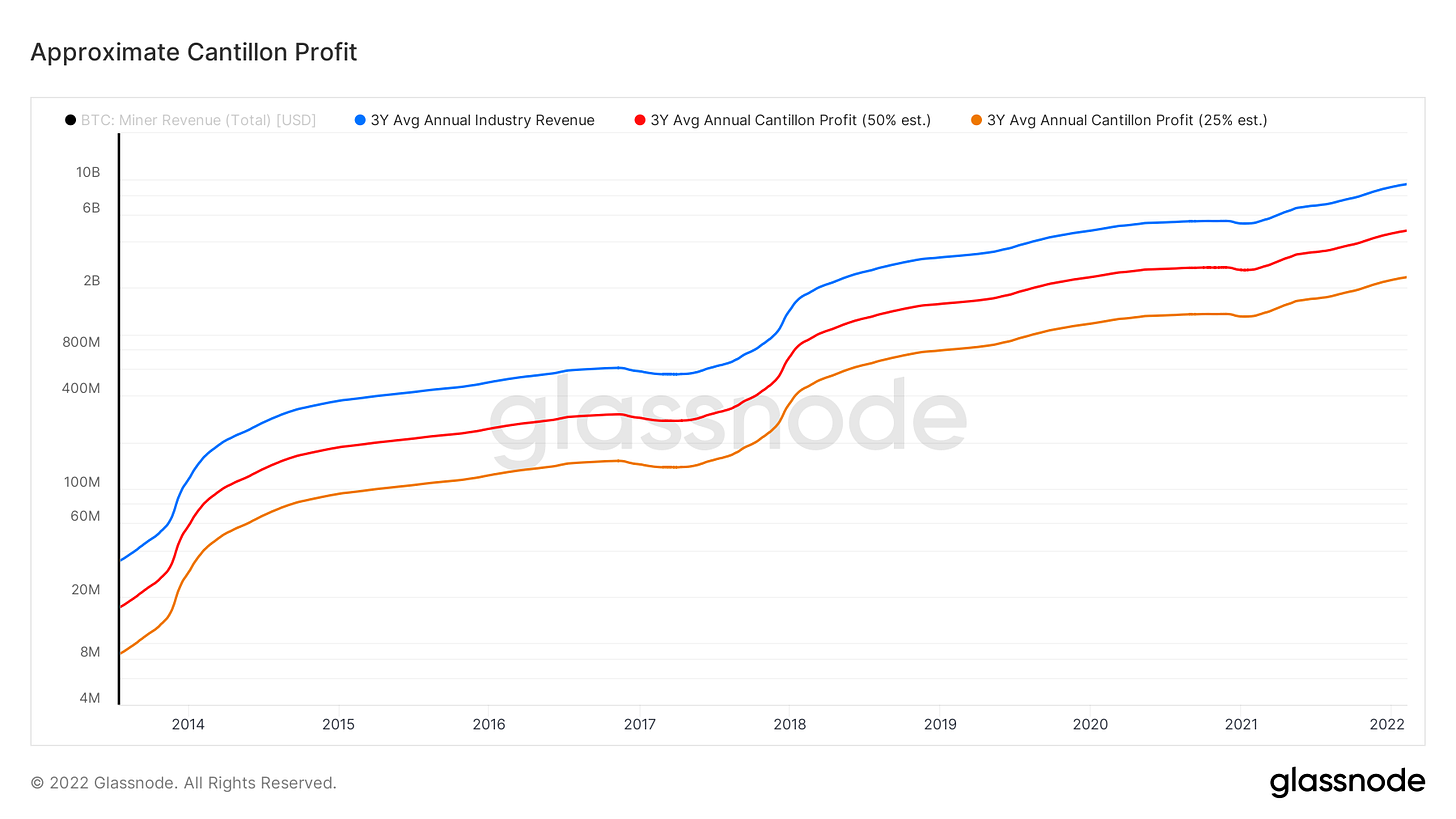

Talking with researchers focused on the mining industry, the all-in profit margins of industrial miners are in the realm of 50% over three years. This suggests that over the past three years, about $4.5 billion (increasing, and over $8 billion in 2021) of profit has been extracted from bitcoin holders annually through unnecessary debasement. This makes for a very attractive investment opportunity, but causes severe harm to the Bitcoin network.

Thankfully, in time the mining subsidy will be reduced and inflation will become negligible, but with the anticipated increase in transaction fees and the gatekeeping of the industry by ASIC-mining, the Cantillon profit will never go away.

Miners do provide vital security for the network, but the competitiveness of the mining industry must also scale and reduce profit to keep the system efficient—the current trajectory leads to bitcoin miners becoming a class of citizen above regular holders, and spits in the face of the inclusive design and equality that underpins the protocol. It is clear from Satoshi’s response to the first bitcoin GPU miner that they foresaw the rise of industrial mining, and the resulting wealth concentration—wanting to delay or dampen it as much as possible.

Industrial bitcoin miners are functionally identical to the gold miners and shipping merchants that Cantillon rallied against.

Proof-of-Stake Protocols

Author’s Note

Before diving into the inflationary dynamics of PoS (Proof-of-Stake) protocols, I would like to explicitly remind the reader that this writing is not a discussion of the relative security between Proof-of-Work and Proof-of-Stake, nor is it a discussion of the energy intensity of the systems. The focus is on the difference in inflationary dynamics and Cantillon profits.

Proof-of-Stake is often criticized by bitcoin maximalists as having a large Cantillon Effect, but this stems from a surface level understanding of the mechanism and either a lack of desire to investigate Proof-of-Work alternatives or a financially driven desire to discredit them.

To begin, consider the following question: is a stock split inflationary? As an external observer you could try to make an argument that it is, but because the dilution is distributed back to the shareholders, no one is hurt by the action: the issuance of new shares or tokens doesn’t automatically create bad-inflation or Cantillon events.

Let’s now consider a theoretical, fairly-implemented and free-to-run, PoS cryptocurrency where 100% of the token supply is staked by users. In this imaginary scenario, the staking rewards can be thought of as a continuous randomly-awarded stock split. If there is equal demand between new market entrants and those looking for exit liquidity, the market capitalization of the cryptocurrency should be constant. With a stable market cap and increasing supply of tokens, the price of each token naturally falls, but each holder’s loss per token is offset by their staking rewards.

In the limit, Proof-of-Stake suffers from no Cantillon Effect and has no harmful inflationary mechanism.

In a contrived scenario with unrealistic assumptions all is well, but in practice is there harmful inflation and a Cantillon effect? Let’s unpack each assumption and see how the incentives and beneficiaries change.

Fairly Implemented

To be fairly implemented, in this context, there are only a few requirements:

- staking rewards (in percentage terms) must not scale with the amount staked;

- staking must be available to everyone (including through staking pools and staking on exchanges);

- the selection of validators must be fair.

Without diving into the technical details, those three statements are true. The requirement of having 32 ether to become a validator is a hurdle to the definition, but with free market alternatives like staking your tokens on an exchange, joining a staking pool, and products like Lido, access is available to all for a nominal and competitive fee. These workarounds do however introduce a small Cantillon profit (to be discussed in the following section).

Free-to-Run

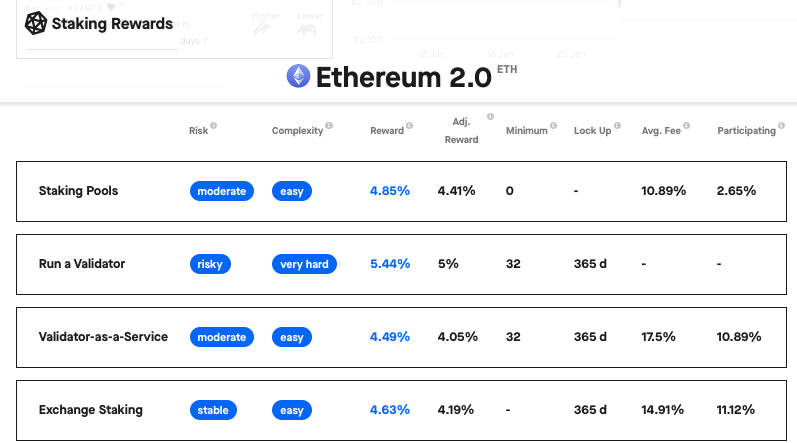

Ethereum validators are not free to operate, but compared to PoW mining the cost is small. One way to gauge a max-cost estimate is to look at the fee paid to staking pools, as pool operators would not choose to run at a loss. The spread on stakingrewards.com is currently 0.59%, or approximately 11% before accounting for tip rewards1.

Source: stakingrewards.com as of Feb 13, 2022

Exchanges appeal to less technical users and are slightly more aggressive with their fees taking a cut of 0.81%. More technical users have the option of outsourcing the operation to Amazon Web Services, while highly technical users can operate their own server and run their own validator.

Since staking rewards, through the analogy of a continuous stock split, are non-Cantillon, the only inefficiency in the process leading to wealth inequality or distortion of the market is the profit margins between the cut taken by staking pools and the cost to run the validators. We can put an absolute upper bound on the Cantillon profit by assuming the cost of running a staking pool is zero.

The max possible Cantillon profit from Ethereum staking is currently 0.6% of all staked ether. With 7.8% of the currently supply of ether staked this puts the maximum limit at 0.05% per year—about $17.5 million annualized. On a market-cap adjusted basis, the profit extraction in this worst case is less than 1% of the three-year average profit extraction by bitcoin miners.

As the supply of staked ether rises the theoretical Cantillon profit will increase but remain bounded by the spread between rewards and staking pool payouts. Even if every ether token was staked in a staking pool and all the pools were able to operate without cost while not having to compete on fees past the current level, the market cap adjusted Cantillon profit would still be smaller than that of bitcoin miners.

100% of Tokens Are Staked

Having every token staked is a convenience for the thought experiment, but isn’t a necessity, nor will it happen. The important distinction is that we’re interested in the supply dynamics from the point-of-view of a staked token. Anyone choosing not to stake their ether (to use in DeFi, for liquidity purposes, because they don’t understand the dynamics, etc.) is foregoing their rewards and essentially paying a tax to avoid securing the network—a tax via debasement.

Because there will always be a share of the supply that remains unstaked, the ownership share of any singular staked token (and its rewards) is constantly increasing. Put differently, when accounting for rewards, staked ether is guaranteed to be deflationary.

This is before accounting for token burning via EIP-1559.

Equal Demand Between Market Entrants and Exit Liquidity

This assumption was made to stabilize the market capitalization of our theoretical cryptocurrency and draw precise conclusions about resulting price changes in the model.

In reality, the demand for tokens and demand for exit liquidity will be constantly mismatched causing price fluctuations. In the short-term price movements are unpredictable, but in the long-term the demand for exit liquidity will be lower than the PoW surrogate because the operating expenses to secure the network are significantly lower. This drop in the demand for exit liquidity is a main component in SquishChaos’s Triple Halving Thesis, and the largest driver in my Flows Model.

Ethereum 2.0

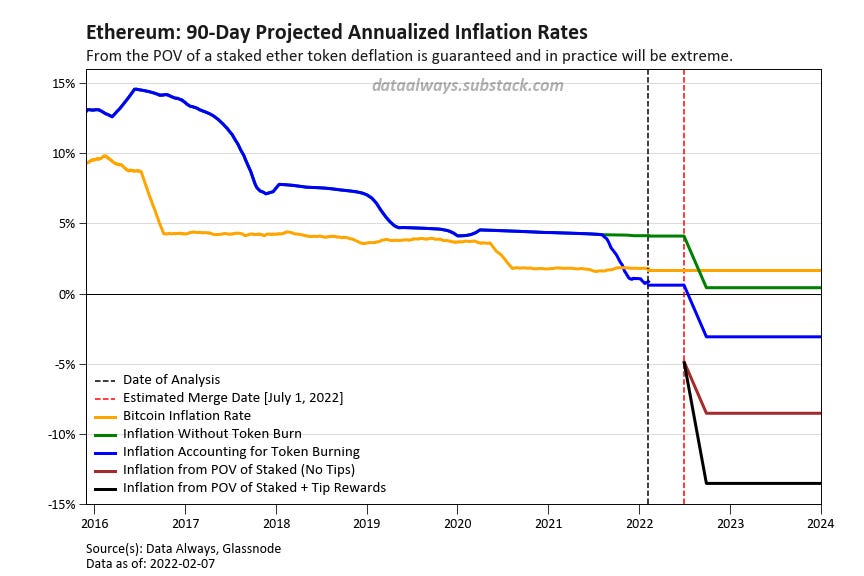

The main takeaway from the thought experiment above should be that since post-merge staking rewards are internal, available to all, and fairly distributed they do not generate Cantillon profits. Instead of modeling staking rewards through a traditional income generation lens, they are better viewed as deflationary mechanism. Combined with EIP-1559 token burning, the effects will become extreme.

In the figure below, we discard the idea of using staking rewards as income and examining the relative inflation and deflation share of one’s holdings for different staking and burn conditions.

The worst scenario is that you choose not to stake your ether and token burning falls to zero. In spite of your choice not to stake, the debasement of your holdings, given current staking levels, would still be lower than the debasement that all bitcoin will suffer for the next six years (two more reward halvings).

If token burning continues at its current rate, unstaked ether will be deflationary at approximately a 3% supply reduction annually. I’ve only analyzed the short-term data, but my understanding is that this eventually leads to a long-term supply equilibrium.

The true strength is looking at the market share of a staked token: without accounting for tip rewards a staked token and its rewards will see a deflationary supply of approximately 8%, and assuming tip rates remain at their current level after the transition to PoS would see approximately 14% deflation annually.

As the supply of staked ether grows these numbers will moderate, but even at staking rates of 50% or higher will remain significant.

These expected deflation rates are available to anyone who chooses to hold and stake their ether, make no assumptions about demand, and thus the inflation is entirely non-Cantillon. Because the issuance is internal and available to all holders equally, there is no rich-get-richer effect—instead anyone who chooses to support the network is rewarded, independent of the size of their holdings.

Token holders choosing not to support the network are making an active choice to pay tax through debasement, and therefore rewards for Ethereum 2.0 are still functionally identical to a continuous stock split. Every token holder has the same proximity and access to the money printer.

Bitcoin holders tend to claim that, because Ethereum’s monetary policy doesn’t have the immutable history that bitcoin’s monetary policy has, there is the potential for issuance to increase in time. However, because that issuance is internal and fed back into the system, a staker perceives an increase in issuance as beneficial to their market share. Deflation is guaranteed for a staked holder of ether no matter how the issuance changes.

The switch to PoS isn’t a part of a triple halving, it’s infinite halvings applied at once.

-T.