How Firm might succeed in (finally) bringing innovation to legal contracts

Tl;dr: Firm can streamline the negotiation of traditional legal contracts by offering users a new incentive to use automated legal tools, real-time control over organizations

Recently Firm announced the launch of its v1 protocol that, at a high level, allows users to build the infrastructure for their internet-native organizations on-chain by leveraging Safe, the ubiquitous multi-sig protocol.

What’s perhaps most interesting is Firm’s ability to mirror the on-chain organization in an off-chain traditional legal structure (if the user so chooses). From Firm’s documentation:

Firm builds software and legal infrastructure so that companies can be primarily digital. Primarily digital means that the company’s ‘canonical representation’ is a series of smart contracts, even if a legal structure representing the company exists to mirror the digital structure. … The vision is that people interact with the digital product and perform actions on-chain while legal compliance is automated in the background.

In other words, the traditional legal contracts that define an organization will follow the smart contracts that define (and actually constitute) the organization. Why? Because, in an internet-native organization, what matters most is the multi-sig and the smart contracts. The traditional legal contracts are only necessary for interaction and/or compliance with the traditional legal regime.

Creating better infrastructure for internet-native organizations and streamlining how they engage with the real world is an incredibly exciting and ambitious project. However, I will also argue that Firm is uniquely positioned to innovate in an industry that has been notoriously static, traditional legal contracting. To begin, let’s illustrate how others have tried to innovate previously.

Layer 1 and Layer 2: Contracts and Filters

The base case

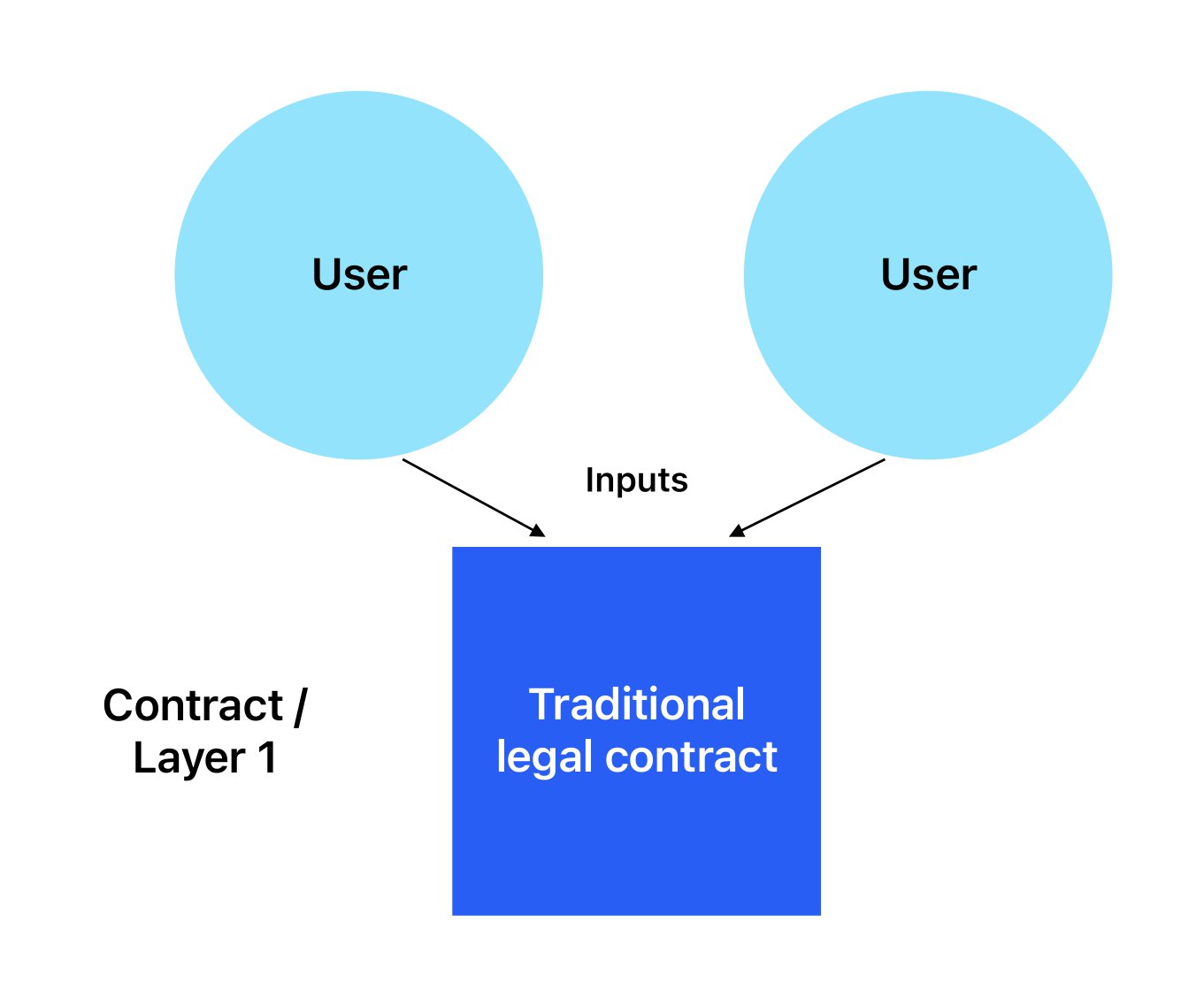

Anyone can write a legal contract. In the Anglo-American (common law) legal system, the intent of the parties to a contract is what ultimately determines how a contract is interpreted. So, generally speaking, nothing prevents two people from writing their intent down and creating an enforceable contract. Of course, for a variety of reasons (some good, some bad) traditional legal contracts are complicated and difficult to understand - “what do these words mean? “is this what people usually agree to in these situations?” “will this clause have any knock-on effects that aren’t obvious?”

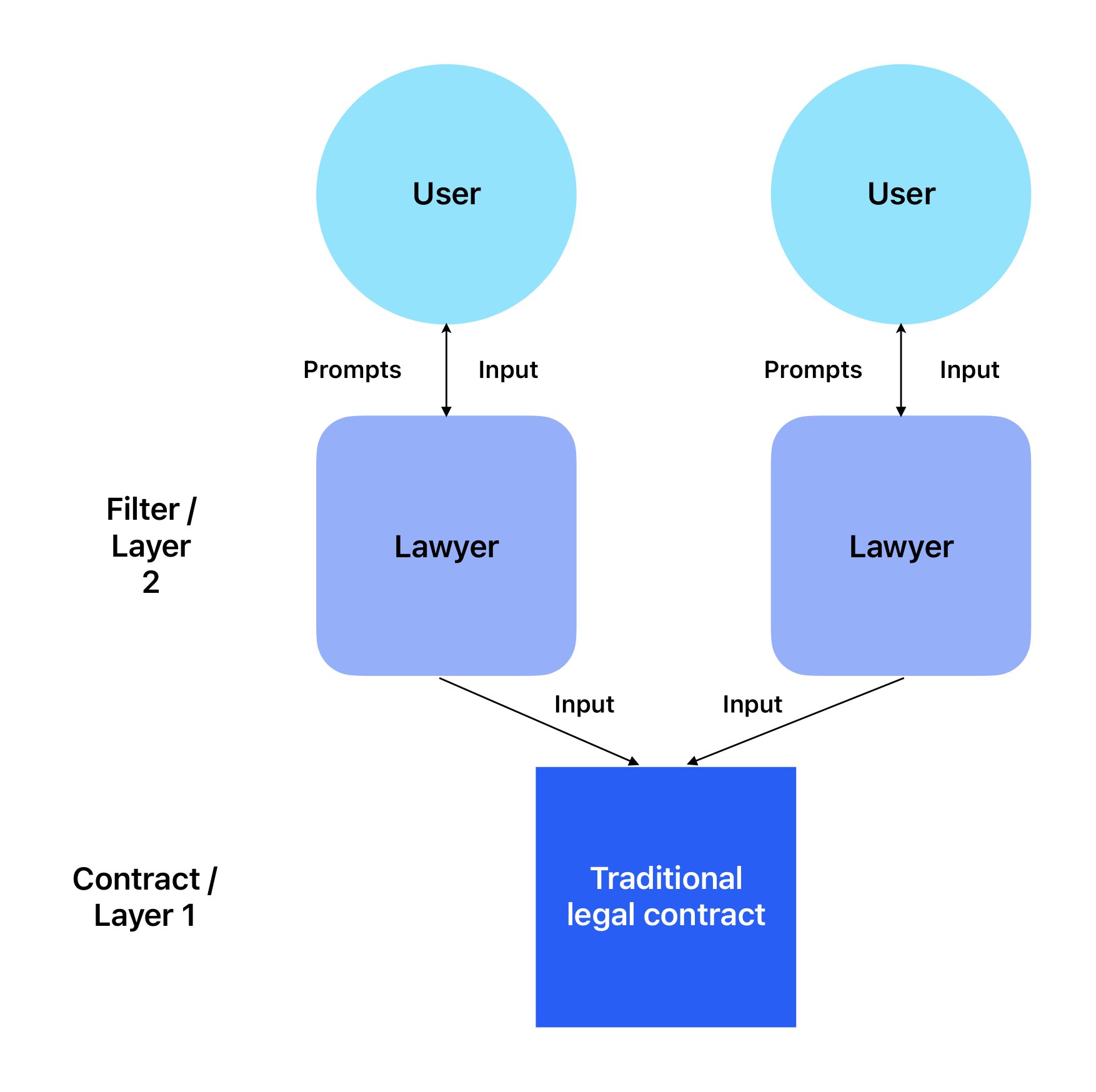

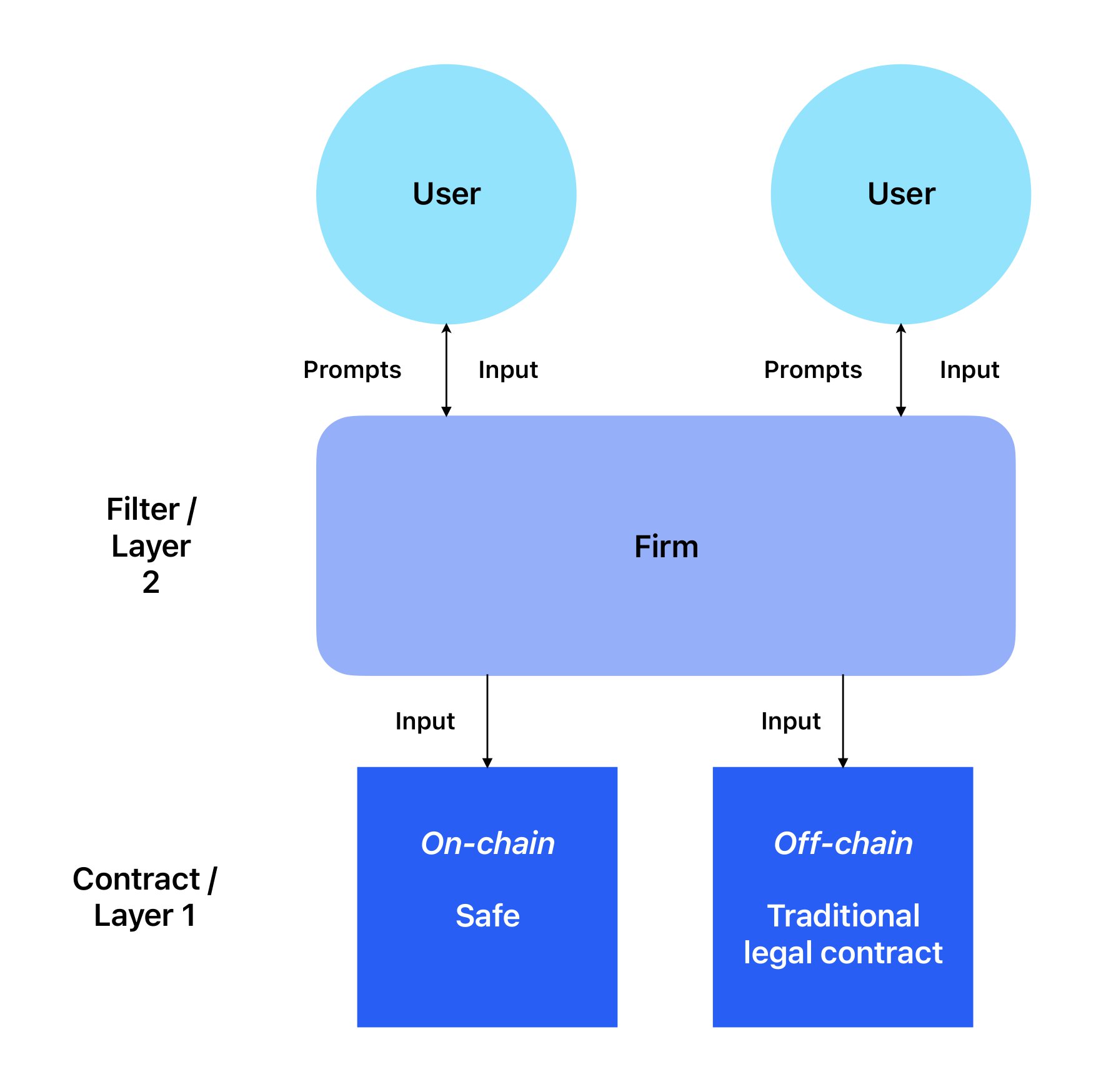

Lawyers help non-lawyers, the users, answer these questions. In doing so, lawyers act as a filter for the user, helping the user more efficiently create a contract and engage with the traditional legal system. To draw a loose analogy, the lawyer acts as a layer 2 that allows a user to more efficiently, though indirectly, interact with the layer 1 (the actual legal contract).

The static layer 1

Although lawyers help users accomplish what they want to do (create a traditional legal contract), they aren’t costless (a very large topic that’s better addressed another day). So, rather than use a costly layer 2 (lawyers), can’t we just make the layer 1 (traditional legal contracts) more efficient and easier to use? Can’t we just throw out the legalese and write contracts in short, plain English?

Of course, we can (and people do) write simple, plain-English contracts (and, as noted above, these will be enforceable). But many of the words, phrases and concepts used in traditional legal contracts are used because they’ve been interpreted, or are understood among practitioners, to mean something particular. If users only write simple, plain-English contracts, they risk losing some of the benefit of using the layer 1 in the first place, strong assurances that their intent is fully captured and enforceable against others.

So - even if we could get past the inertia and institutional interest in having complicated contracts written in legalese - there is a benefit to leaving the layer 1 (traditional legal contracts) static (or, at least, allowing innovation to remain slow). Still, even if the benefits of innovating at the layer 1 don’t outweigh the costs, we can innovate at the layer 2.

Layer 2 Innovation

Current layer 2 innovation…

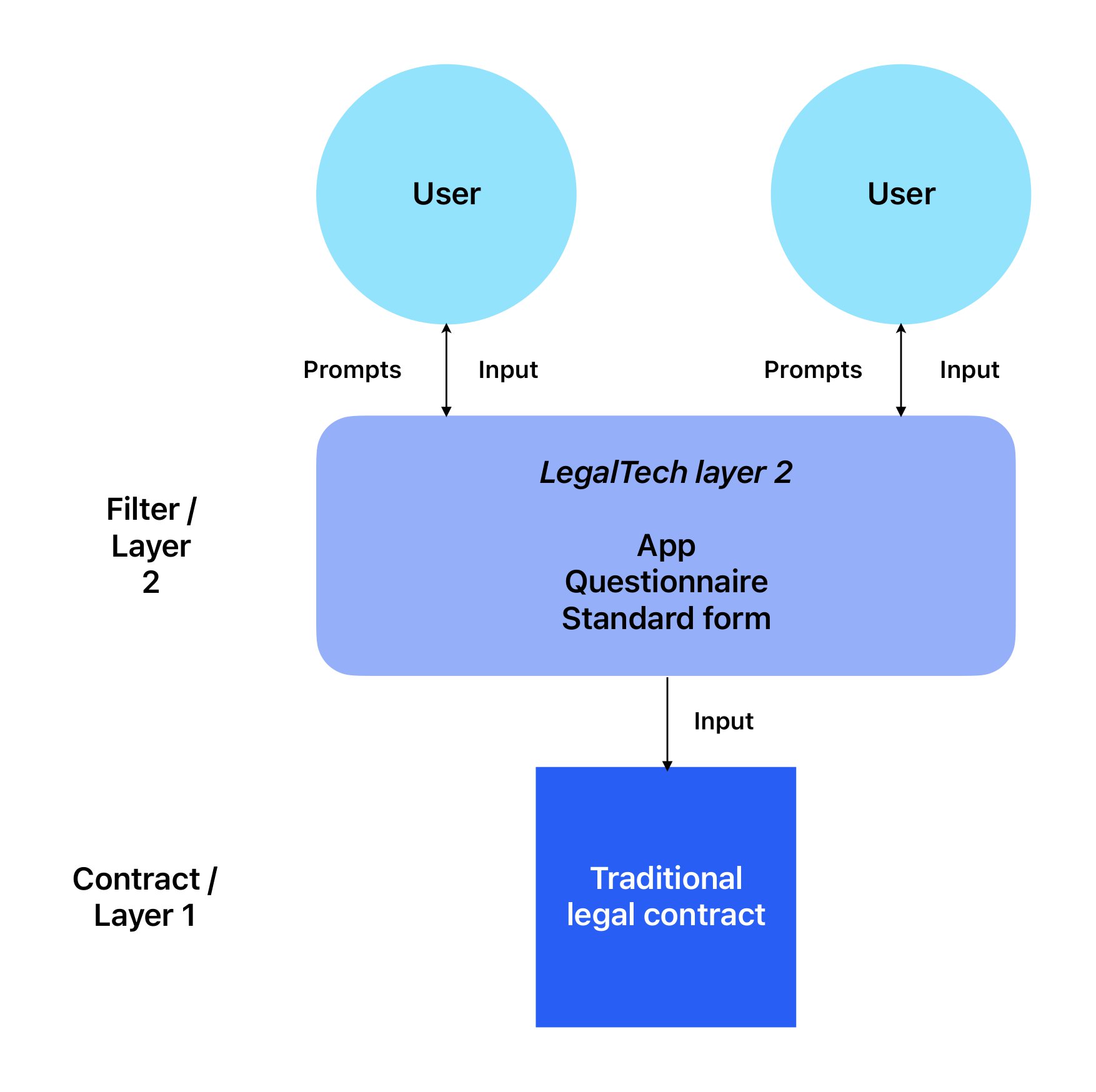

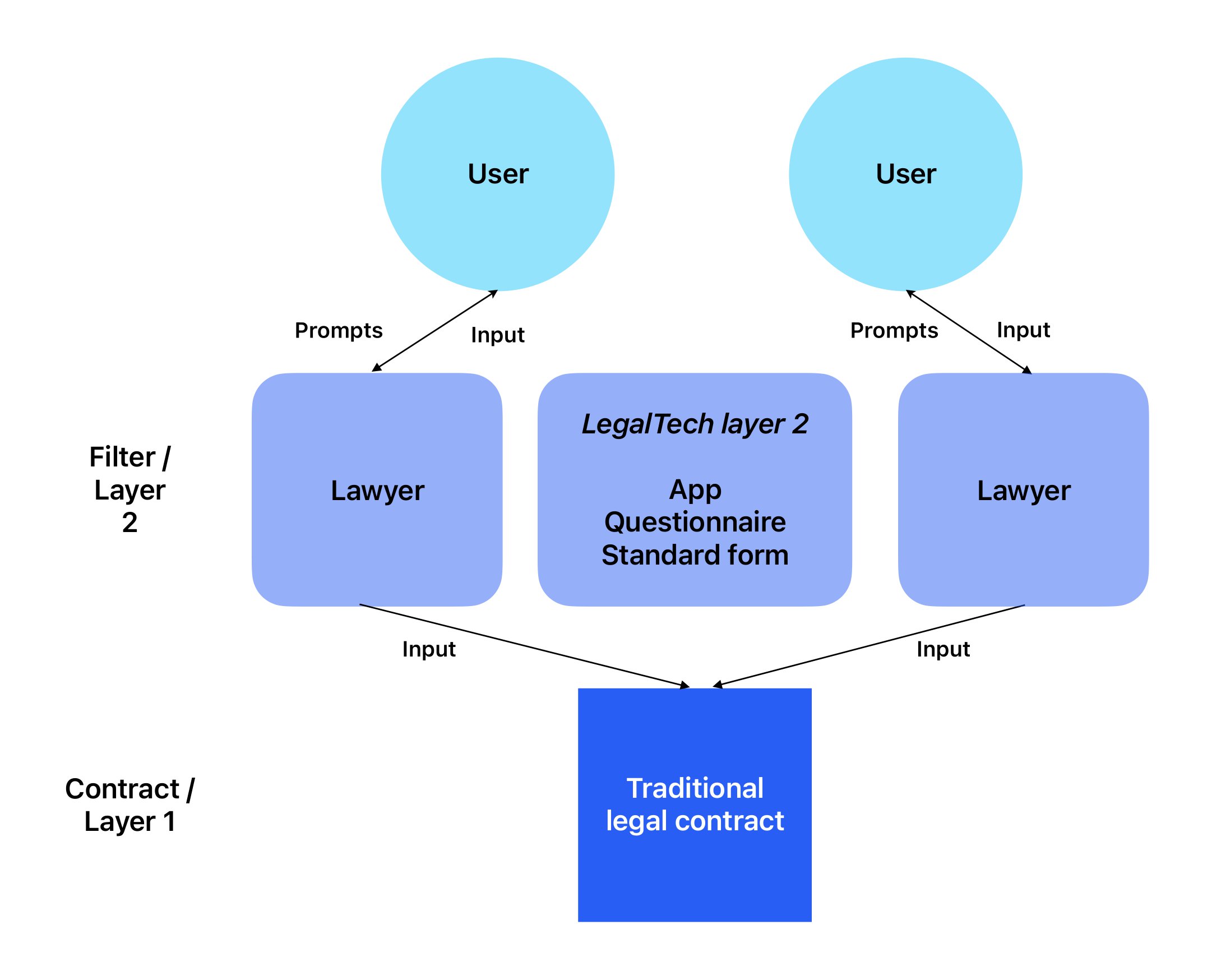

Because layer 1 innovation is difficult or not worthwhile, innovation is pushed to layer 2. Law firms and lawyers themselves (the original layer 2s) have innovated, but there has also been an effort to automate the filter between users and traditional legal contracts (let’s call them “LegalTech layer 2s”). So, instead of the user feeding inputs to a lawyer, who then feeds inputs to the contract, the user feeds inputs to a form, questionnaire or app (think LegalZoom, Rocket Lawyer, Cooley Go, Orrick’s Startup Library, Y Combinator’s SAFE, NVCA Model Legal Documents):

…and why it hasn’t scaled yet

LegalTech layer 2s work well for traditional legal instruments (documents that aren’t negotiated between two or more parties - think powers of attorney or wills), but less well for traditional legal contracts. The primary reason LegalTech layer 2s haven’t achieved mass adoption within contract negotiation is, I think, because both parties to the contract need to “buy into” the particular layer 2 being used. If one party is comfortable that a standard form (for example) is fair, there’s no efficiency gained if the other party isn’t comfortable and wants to make changes to that form. Even the party that was originally comfortable with the form has to consult with a lawyer once the other party makes changes to the form. In my experience, it’s very rare that both parties are comfortable with the same layer 2. And, as a result, users end up relying on lawyers even when a LegalTech layer 2 is involved at the outset.

To summarize, LegalTech layer 2s innovate across a single dimension: better prompts, leading to better inputs into the traditional legal contract (in other words, a more efficient lawyer). And these layer 2s have not taken meaningful market share from the lawyers (the original layer 2s) because the potential efficiency gains for each party rarely outweigh the assurances that can be provided by lawyers for that party. Firm, however, is innovating across multiple dimensions.

Firm’s Advantage

Real-time organizational control

Unlike LegalTech layer 2s, Firm isn’t aiming to create a more efficient lawyer. Instead, it’s focused on offering a better product (an organization constituted by smart contracts and, thereby, canonically digital) than is available in the traditional legal world (a corporation constituted by traditional legal contracts). Again, from Firm’s documentation (emphasis added):

Companies running on Firm have stronger guarantees and tighter controls than fiat companies. A fiat company (a company with a legal core) has to rely on the threat of post-hoc legal repercussions for misconduct and breaches of trust. Internet-native companies can be very explicit about how power is delegated all the way from shareholders and companies are inherently transparent due to the fact it runs on a public blockchain.

Consider an investor in a company that wants the right to approve expenditures over a certain amount. Traditionally, to effect that right, the company’s organizational documents (for a Delaware corporation, the certificate of incorporation or “charter”) will specify that the company cannot make expenditures above that amount without that investor’s consent (or, technically, the consent of the stockholders that hold certain shares of preferred stock in the company). If the company does spend more than is permitted without the investor’s consent, the investor will have a remedy against the company, but it’s unclear what the remedy is. Can the investor force the third party to give the money back to the company? Probably not. Does the investor’s liquidation preference increase by the amount of the expenditure? Again, probably not. Ultimately, a court will have to determine, post-hoc, what the investor’s damages are. The investor would much rather prevent the transaction from occurring in the first place. That’s what Firm allows.

Innovation as a byproduct

Firm also allows organizations to “opt into having an off-protocol legal entity (bringing the same level of protections of a fiat company).” This ability to opt into the traditional legal world is valuable - it offers the benefit of limited liability and smoother interaction with off-chain companies, among other things. If an organization elects to use an off-chain entity, the operative structure of the on-chain organization will be automatically (from the user’s perspective) mirrored in the off-chain entity. To continue our example: on-chain, the Safe underlying the organization will require the investor’s signature before a certain amount of funds are sent and, off-chain, the legal entity’s charter will require the investor’s approval before those funds are sent.

To facilitate off-chain legal structures mirroring on-chain controls, Firm will standardize the traditional legal contracts for organizations on the platform. Standardization is the only means through which this process can be done automatically and at scale. So, while Firm’s primary use case is offering real-time control over a digital organization (in a manner that is not possible within traditional organizations), the standardization of traditional legal contracts is a secondary benefit of the protocol. In fact, it’s because standardization is a secondary (and not primary) function that Firm won’t face the same problem faced by LegalTech layer 2s. LegalTech layer 2s rely on a single incentive to attract two parties to their products - more efficient negotiation. But Firm offers a different incentive - better organizational control. More efficient negotiation just happens to be part of the package.

The Opportunity

Firm offers improved control within an organization, so it’s clear how the standardization that will accompany that control can affect an organization’s constituent contracts, the charter, the bylaws, etc. It’s less obvious how Firm’s protocol can have an effect on other contracts, those with employees or other organizations. It seems to me, however, that Firm can influence those other traditional legal contracts by, in the short-run, offering substantive advantages and by, in the long-run, acting as a Schelling point around which all contracting is done.

The short-run

Consider a company created using Firm. Like many startups, the company wants to grant equity to early employees and, as a condition to the equity grant, the company requires the employee to sign an IP assignment agreement (an customary agreement under which an employee agrees that any IP created by the employee in the course of her employment will be owned by the company, rather than the employee). Because the company was built using Firm, it will likely use Firm to issue the equity to the employee (cap table control is one of Firm’s launch features). To prepare the IP assignment agreement, the company could use a lawyer or an appropriate LegalTech layer 2. But, if the company uses a form IP assignment agreement developed by Firm, the company will be able to natively tie the execution of the IP assignment agreement to the equity issued to the employee. So, for instance, the protocol will prevent the equity granted from being sold unless or until the employee has executed the IP assignment agreement.

Firm can establish rules (or allow organizations to establish rules) for what qualifies as, to continue the example, an acceptable IP assignment for purposes of satisfying the equity grant condition. And it can then draft a form traditional legal contract that satisfies those conditions. In other words, the Firm protocol will “know” what the terms of a Firm-drafted traditional legal contract says. Similarly, it won’t know (or be able to interpret) what other traditional legal contracts say, there’s simply too much variability. As a result, companies built on Firm will have an incentive to use Firm-drafted traditional legal contracts.

The long-run

But consider a company created using Firm that wants to enter into a contract with a much larger traditional company (one not created using Firm). Even if the Firm-created company would benefit from using a Firm-drafted contract, the other company may not like that form and may have enough leverage to use its own preferred form contract. This is the problem faced by LegalTech layer 2s discussed above and Firm isn’t immune to it. However, over time, I expect more and more companies to be built on Firm. Those companies will be accustomed to using Firm-drafted contracts and, as a result, Firm, as a protocol and a brand, could become a Schelling point for all contracting. In other words, even in cases where there is no “substantive” benefit to using a Firm-drafted contract, Firm could evolve into the “natural starting place” for all contracting simply because so many companies will have begun life using Firm-drafted contracts.