Abstract:

The US petrodollar system, established in the mid-20th century, has long been a defining force in the global economy, fostering both monetary and political hegemony for the United States. Recent developments, however, threaten to upend the dominance of the petrodollar, posing significant risks to the stability of the international financial architecture.

As the decline of the petrodollar becomes increasingly evident, this article explores the transformative potential of blockchain technologies and digital currencies to offer an alternative. This analysis delves into the possibilities presented by Bitcoin, Ethereum, stablecoins, and Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) as viable replacements, discussing their integration in real-world systems, addressing scalability and sovereign concerns, and identifying necessary infrastructural developments.

Introduction

The intricate tapestry of the world's economic and political landscape has long been marked by the pervasive influence of the US petrodollar system. This mid-20th-century creation has granted the United States exceptional power, which now faces threats from evolving internal and external dynamics—both posing considerable risks not only for the US but also for the global financial system (Skidelsky, 2008)¹.

The Genesis: Foundations of the Bretton Woods System

To appreciate the magnitude of the petrodollar's impact, its origins must be traced back to the Bretton Woods agreement of 1944. At this pivotal gathering, world leaders reached a consensus that would directly and indelibly shape future economic relations: they agreed to peg their respective currencies to the US dollar, which would in turn be pegged to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce. This arrangement fortified the US dollar's position as the de facto global reserve currency, its value tethered to the gold standard (Eichengreen, 2011)².

Adaptation: The Fall of the Gold Standard

Nonetheless, as the decades unfolded, the gold standard became increasingly untenable. Fueled primarily by burgeoning global debt and the inflationary pressures wrought by the Vietnam War, this once-revered financial linchpin began to show cracks. The situation reached a boiling point in 1971, as President Richard Nixon made a momentous declaration: the gold standard would be suspended, unleashing a period of unprecedented currency fluctuations and widespread economic uncertainty.

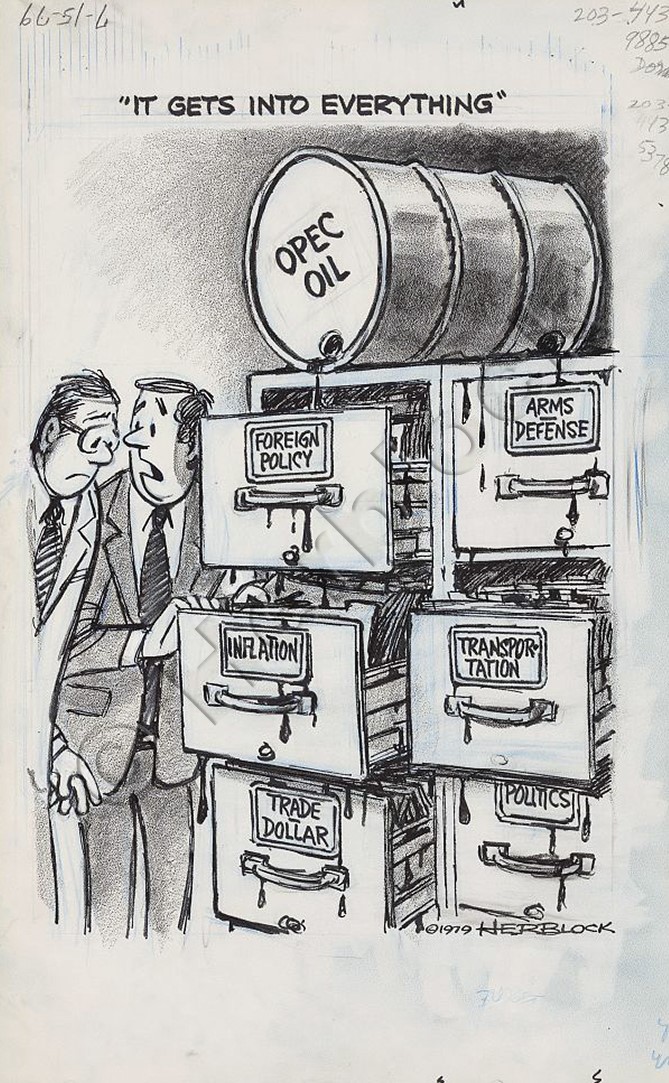

This turbulent landscape, however, would not remain in disarray for long. In the years that followed, the US laid the groundwork for a new financial order, entering into negotiations with Saudi Arabia. The fruit of these talks would prove to be world-altering: an agreement to price oil exclusively in US dollars. As other OPEC nations (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) adopted this practice, the world's reliance on the dollar—and the emergence of the "petrodollar"—was solidified (Ghizoni, 2013)³.

Symbiote to Parasite: The Petrodollar and the Modern US Dollar System

To comprehensively understand the urgent vulnerabilities facing the current petrodollar system, its relationship with the modern US dollar system must be examined.

The United States' reliance on the petrodollar system is characterized by its dependence on foreign nations processing oil transactions in US dollars, which in turn channel those funds back into the US economy. This phenomenon, also known as petrodollar recycling, is facilitated through the purchase of US Treasury securities, direct investment in US-based assets, or maintaining dollar-denominated reserve holdings by the central banks of oil-exporting countries. Consequently, the petrodollar recycling mechanism bolsters the demand for US dollars and supports the US economy through the provision of credit and liquidity.

Given the crucial role of the petrodollar in buttressing the US dollar system, any disruption to the former is bound to have profound implications for the stability and potency of the latter. This precarious interdependence renders both the petrodollar and the US dollar system susceptible to external shocks, such as fluctuations in oil prices, geopolitical tensions, or shifts in the global economic order. For example, a sudden decline in the demand for oil or a shift towards alternative energy sources could lead to reduced demand for US dollars, which may exert downward pressure on the value of the US currency and potentially exacerbate the already burgeoning US trade deficit.

Survival of the Fittest: Dollar Hegemony and Military Force

Throughout subsequent decades, the petrodollar system reigned supreme with its muscular grip on the global economy. The US dollar's preeminence persisted, driving dollar-demand as an essential underpinning of worldwide trade. Yet, beneath this veneer of stability lurked an insidious reality: the United States readily employed its military force to safeguard the dollar's hegemonic rule, a stark illustration of its determination to maintain its grip on power.

In the annals of history, several episodes cast an ominous shadow over the United States' dollar hegemony. Such examples include the Gulf War in the early 1990s, where the US invasion of Kuwait was fueled, in part, by strategic aims to preserve the petrodollar system that influenced oil prices, and the 2003 Iraq War, which was waged in response to Saddam Hussein's decision to conduct oil transactions in euros (Ferrantino, 2013)⁴.

In recent years, other nations—among them, Iran and Libya—have sought alternatives to the US dollar to resist its far-reaching influence. These efforts were met with aggressive isolation and punitive measures meted out by the US Government, a telling reflection of America's unyielding commitment to preserving its monetary hegemony and the petrodollar's coveted stature (Looney, 2012)⁵.

Rising Competition: The Emergence of New Financial Species

The petrodollar system now faces formidable challenges from several fronts, chief among them China's refusal to purchase more US bonds. This policy has precipitated a steady decline in demand for the US dollar, while China's efforts to internationalize its currency, the yuan, pose further complications to the petrodollar (Prasad, 2014)⁶.

The burgeoning economic collaboration and independent monetary policies between China and Russia also present formidable challenges to the dollar's supremacy. These two nations have been increasingly conducting trades outside the US monetary system (Nekhai, 2016)⁷ and even embarking on the creation of alternative payment systems for oil transactions, thereby weakening the petrodollar’s foundation.

Additionally, China's e-RMB, a digital incarnation of its currency, has thrust itself into the limelight as a formidable rival to the entrenched petrodollar system. Should this innovation prove successful, it could topple the heretofore unassailable position of the US dollar within the global economic order (Auer, 2020)⁸.

Today, the petrodollar finds itself on a precipice, as various factors assail its once-ironclad position in the global economy. As the world races to address the profound and far-reaching implications of this decline, humanity has the opportunity—and the moral obligation—to face the gruesome, fraying infrastructure lurking beneath the surface of this system, which has been underscored by the United States' proclivity for military intervention in pursuit of dollar hegemony.

A New Breed: The Dawn of Blockchain Solutions

As the world finds itself at the precipice of a new era in global financial systems, the end of the petrodollar seems increasingly inevitable. However, this does not have to spell disaster for the US or the world economy. Innovative blockchain technologies and digital currencies offer a way forward, potentially replacing the petrodollar with a more efficient and transparent system.

> Bitcoin

In recent years, the world has witnessed a surge in Bitcoin's adoption and use across various industries, with increasing interest from institutional investors, businesses, and central banks. For instance, El Salvador has become the first country to adopt Bitcoin as legal tender, signaling its growing acceptance (Al Jazeera, 2021)¹⁷. Moreover, companies like Tesla and MicroStrategy have integrated Bitcoin into their financial strategies, showcasing its growing relevance (Ycharts, 2021)¹⁸.

For Bitcoin to become the primary currency for oil transactions, the US and other nations would need to establish a robust regulatory framework, create incentives for the energy sector to adopt the cryptocurrency, and invest in the development of more scalable and environmentally friendly blockchain infrastructures. As central banks around the world continue to explore the potential of digital currencies, a future in which Bitcoin plays a critical role in replacing the petrodollar becomes more feasible.

> Ethereum and Ethereum L2s

The versatility of Ethereum and its embrace of smart contracts present innovative possibilities for its adoption within the energy sector. For example, pilot projects such as the blockchain-based decentralized energy markets in Estonia have successfully enabled peer-to-peer trading of solar energy using Ethereum (WePower, n.d.)¹⁹. Similarly, the oil and gas industry could leverage Ethereum's L2 solutions for streamlining oil transactions.

To implement Ethereum and its L2s in oil transactions, governments and industry stakeholders would need to invest in building and deploying smart contract infrastructures tailored to the nuances of the energy sector, ensuring regulatory compliance and fostering partnerships with key players in decentralized finance to streamline oil transactions.

> Stablecoins

A real-world example of stablecoin adoption is the JPMorgan Coin (JPM Coin), a blockchain-based stablecoin pegged to the US dollar, used for institutional payment settlements and interbank transfers (Reuters, 2021)²⁰. The concept of a commodity-backed stablecoin could be similar, with the currency's value backed by a basket of natural resources, including oil.

Governments worldwide could explore the issuance of their own commodity-backed stablecoins as a means of facilitating oil transactions. To foster adoption, central banks and financial regulators would need to develop a comprehensive framework that outlines the mechanisms for issuing and redeeming these stablecoins, providing clarity and assurance to market participants.

> CBDCs:

The implementation of CBDCs in the global economy has already begun, with countries like the Bahamas and Nigeria having launched or piloted projects to introduce their digital currencies, the Sand Dollar and eNaira, respectively (Quartz Africa, 2021)²¹. These initiatives reflect the growing appetite for CBDCs to facilitate international trade and cross-border transactions.

To transition from the petrodollar to a CBDC-based system, nations would need to engage in multilateral agreements on a standardized CBDC basket for oil transactions while also investing in digital infrastructure to support the widespread use of these currencies. Building on existing research and collaboration among central banks could expedite the development of a pragmatic, transparent, and inclusive CBDC ecosystem that possesses the potential to reshape global oil trade dynamics.

Biodiversity: Envisioning an Equitable and Inclusive Global Ecosystem

Imagine a future where the petrodollar's dominance has been replaced with numerous blockchain-backed currencies. Economic power is more evenly distributed as nations' wealth is no longer defined solely by their access to and control of global oil reserves. This shift paves the way for a more inclusive and equitable global economic environment, with countries experiencing newfound stability in their respective financial markets.

In this hypothetical future, countries accept cryptocurrencies for oil transactions, minimizing trade friction and geopolitical disputes driven by the singular control of one currency. The adoption of blockchain technology fosters greater transparency within international transactions, reduces the time and cost of cross-border trade, and makes market manipulation and sanctions less effective in international disputes. Ultimately, this future is characterized by more substantial financial innovation, resilience, and global economic interconnectedness.

Evolution: Advancing Towards a Decentralized and Adaptive Financial Landscape

As the world stands at the crossroads of a financial metamorphosis, the all-consuming specter of the petrodollar looms large. A system marred by violence, coercion, and relentless pursuit of hegemony, it has proven time and again that its continued reign poses grave perils to global stability. The ghostly echoes of recent bank collapses—SVB, Signature Bank, and Credit Suisse—serve as grim reminders of the fragility that plagues the very foundations upon which modern banking systems are built.

In this age of turmoil and uncertainty, an audacious vision reveals itself: the sublime blockchain revolution.

Offering a cryptographic bastion against the caprices of predatory economic forces, blockchain currencies defy the ostensible nature of modern financial norms by reimagining the paradigms of value and trust on which economies ought to be predicated. To embrace them is to embrace a future where prosperity is bound not by the corrupted legacies of the past, but by the resilient, morally anchored webs of blockchain-driven progress. It is time to reimagine a world woven by the threads of a more equitable and just economic fabric.

References

¹ Skidelsky, R. (2008). The Age of Uncertainty: The End of the Petrodollar System. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2008/feb/03/useconomy.oilandgascompanies

² Eichengreen, B. (2011). Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

³ Ghizoni, S. (2013). The End of Bretton Woods: August 15, 1971. Federal Reserve History. Retrieved from https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/end_of_bretton_woods

⁴ Ferrantino, M. J. (2013). The 1990-91 Gulf War and the Gulf Cooperation Council: A Quantitative Assessment of Multilateral Trade Cooperation. Journal of Economic Integration, 28(2), 203-227.

⁵ Looney, R. (2012). Can the United States and Saudi Arabia’s New Economic Plan Weaken Iran’s Petroeuro Plan? Contemporary Economic Policy, 30(3), 316-331.

⁶ Prasad, E. S. (2014). The Dollar Trap: How the US Dollar Tightened Its Grip on Global Finance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

⁷ Nekhai, A. (2016). Russia and China Challenge Dollar Domination. RT News. Retrieved from https://www.rt.com/business/366564-russia-china-challenge-dollar-domination/

⁸ Auer, R., Cornelli, G., & Frost, J. (2020). Rise of the Central Bank Digital Currencies: Drivers, Approaches, and Technologies. BIS Working Papers No. 880. Retrieved from https://www.bis.org/publ/work880.pdf

¹⁷ Al Jazeera. (2021). El Salvador Makes Bitcoin Legal Tender: What Now? Al Jazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2021/6/18/el-salvador-makes-bitcoin-legal-tender-what-now

¹⁸ Ycharts. (2021). Tesla Bitcoin Holdings. Ycharts. Retrieved from https://ycharts.com/companies/TSLA/bitcoin_holdings

¹⁹ WePower. (n.d.). Estonia: Blockchain-Based Decentralized Energy Market. WePower. Retrieved from https://wepower.network/case-studies/estonia

²⁰ Reuters. (2021). JPMorgan to Launch Digital Bank Coin: JPM Coin Takes on Stablecoins. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/jpmorgan-launch-digital-bank-coin-jpm-coin-takes-stablecoins-2021-10-27/

²¹ Quartz Africa. (2021). African Central Banks Are Beginning to Take Digital Currencies Seriously. Quartz Africa. Retrieved from https://qz.com/africa/2092543/africa-central-banks-take-digital-currencies-seriously-cbdc/