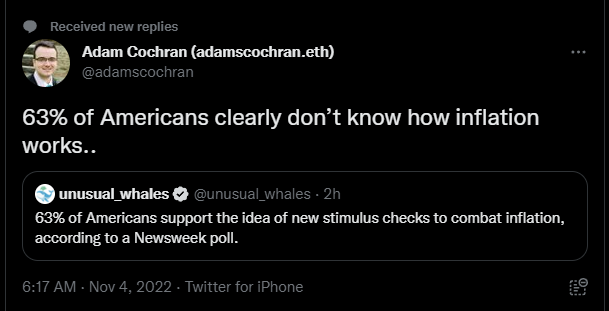

I follow Adam Cochran (@adamscochran) on Twitter because he’s a very smart, very thoughtful guy, who posts insightful (but epically long) tweet-storms. Adam, if you’re reading this, kudos! So, just know that when I’m going to talk about a tweet Adam posted today, I do so with respect for his insights and intelligence. Here’s the tweet:

I actually disagree with Adam’s take. Oddly enough though, I don’t know how much I disagree with Adam’s take. Here’s the part that I know I disagree with: I think that the 63% of people who support new stimulus checks do understand exactly how inflation works. They understand that they receive about the same number of dollars each month through salary or social security and that that number of dollars buys them less food, gasoline, and housing than it did in the past. They feel the reality that their purchasing power has shrunk considerably in the past two years. That’s inflation and they understand it intellectually and in their guts.

I think what Adam is getting at with his tweet is that Americans who support new stimulus checks don’t understand the solution to inflation. I imagine that it goes a little like this: “There are too many dollars chasing too few goods and services, therefore the addition of even more dollars will make those few goods and services even more expensive. Therefore, the solution is to remove dollars from the system rather than increase them with new direct stimulus checks.” Here’s the crazy thing: Despite the validity of this logic, I’m not sure it’s true.

I’m not alone. Determining the cause of inflation based on macroeconomic analysis is really, really hard. Sebastian Mallaby’s book, The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan, notes “‘There is greater not less confusion at the business end of macroeconomics, in understanding the actual causes of macroeconomic fluctuations, and in applying macroeconomics to policy-making,’ the prominent MIT professor Stanley Fischer observed in 1988, confessing to the limitations of the models that he had helped to develop. Across academia such pessimism has become standard. ‘Today, macroeconomists are much less sure of their answers,’ N. Gregory Mankiw of Harvard declared in the Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking.” (pp. 335-336.)

Here’s why I think it’s not super clear that stimulus checks will wreck the Fed’s efforts to bring down the rate of inflation:

(1) Stimulus checks to households with higher income don’t get spent on products or services at all. Instead, the money is mostly used to pay off debt or add to savings. Although this might support spending at some point in the future, it does not contribute to immediate demand that spurs inflation.

(2) About a 30% of lower income households devoted some portion of their stimulus checks to clothing and electronics. At this moment, neither category is a driver of inflation.

That boom in used vehicle prices is also moderating.

(3) In lower income households, the lion’s stimulus checks got spent on food, housing, and utilities. Inflation is rampant in these categories. As I wrote yesterday, however, the problem of inflation in these categories is massively affected by cost factor originating outside the US. The price of fossil fuels and wheat are being affected by war in the Ukraine. The price of many consumer goods depends on supply from China. Until and unless you inflict a lot of pain, you’re not going to solve inflation just on the demand side. Supply is a huge problem here.

That said, the price of housing is pretty directly affected by interest rates and very amenable to the Fed’s interest rate policies. Low interest rates created a massive surge in housing prices for buyers and renters. Zero interest rates set the house market on fire.

(4) What about other causes of inflation? This is where it gets really hard. One thing that Greenspan recognized is the importance of the wealth effect: when people look at their stock portfolios and Zillow estimates of their houses, they will spend more if they “feel rich” based on those holding. One homeowner writing himself a $150,000 home equity check injects a ton of buying demand into the economy. One equity holder who makes a killing in the stock market and decides to splurge “a bit” dwarfs the spending of dozens of lower income households receiving stimulus checks. Another thing that economists used to believe more strongly, was that governmental budget deficits lead to higher inflation. What I’m suggesting here is that the trillions of dollars injected into the economy by QE were much, much larger in both quantity and effect than the stimulus checks sent to US households.

(5) If you sent $1,500 stimulus checks to every household in the US, it would cost only about $250 billion. But remember that households earning $75,000 didn’t spend their stimulus checks on those categories of goods/services where inflation is now worst. That means you only have $125 billion that would chase goods and services and 30% of households would spend at least some of their stimulus on categories where inflation isn’t rampant. Compare that $100+ billion to the $13 trillion dollars that the Fed injected with QE. I’m not sure that $100+ billion of new stimulus checks would break the Fed’s inflation-fighting effort.

(6) To the contrary, I think new stimulus checks would have second-order effects that might help the battle against inflation. If consumers (read: voters) receive stimulus checks, they are less likely to stage a voter revolt that knee-caps efforts to fight inflation. The Fed may look independent, but Arthur Burns and Allan Greenspan keenly felt the political pressures bearing on interest rates. Here, I highly recommend Mallaby’s book on Greenspan. There is a reason why nearly all children’s medicines are made to taste like cotton candy or grape. (Albeit only vaguely.) You can’t sell bitter medicine, but you can get away with medicine that tastes vaguely sweet.

(7) It’s good trade: add $100 billion or so that the agenda of subtracting some of the $13 trillion added by QE can continue. That’s why I’m not so sure stimulus checks are a horrible sweetener for the Fed’s bitter medicine.