This text was initially written as part of my thesis for the Executive Master in Art Market Studies 2023-25 at the University of Zurich and later updated for a journal submission.

Abstract

This study examines the emerging trend of museums integrating Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) into their permanent collections and the technical challenges they face in preserving these digital assets. Despite widespread media narratives declaring NFTs obsolete following the market downturn of 2022, leading cultural institutions have continued to embrace this technology as a legitimate form of artistic expression. The study traces institutional NFT adoption from early pioneers like the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna (2015) through recent major acquisitions by the Museum of Modern Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Centre Pompidou.

While museums pursue NFTs for artistic merit and audience engagement, they encounter significant conservation challenges that most institutions are ill-equipped to address. These include blockchain-related costs for hardware and specialized programming languages, concerns about network decentralization and long-term viability, content storage complexities, and security vulnerabilities. The research reveals that established time-based media preservation challenges are compounded by blockchain-specific technical requirements, creating new institutional capacity demands. Museums must develop comprehensive pre-acquisition protocols, specialized staff expertise, and robust archival systems to ensure the long-term preservation of NFT-based artworks. This institutional adoption represents a critical juncture in legitimizing NFTs within art historical canon while highlighting urgent needs for technical infrastructure development in cultural preservation.

Introduction

While NFTs emerged as a mainstream phenomenon in 2021, their roots trace back to the early days of blockchains. One of the first digital artworks to be minted as an NFT in May 2014 was Kevin McCoy's "Quantum" (Liscia, 2021), predating the NFT boom by seven years. Forward-thinking institutions like the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna, the ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, and the Whitney Museum in New York had already begun acquiring NFTs long before these digital assets gained widespread recognition. These early developments demonstrate how blockchain-based art had been developing incrementally for years prior to the Beeple sale of "Everydays: The First 5000 Days" capturing global attention.

The euphoric NFT boom of 2021-2022 quickly transformed into a cautionary tale of speculative excess, as market participants driven by inflated valuations and media hype eventually succumbed to growing skepticism about the sustainability of such price levels. By 2022, prices across most NFT collections had declined precipitously, with trading volumes and market capitalizations failing to recover their 2021 peaks, prompting widespread declarations of sector collapse. This dramatic market correction led critics to dismiss NFTs as a temporary aberration, conflating speculative trading dynamics with the underlying technological and artistic innovations that had been developing independently of market valuations (Hawkins, 2023; Klee, 2023).

The binary rhetoric of boom and bust obscured the more nuanced reality that while speculative trading had indeed crashed, the foundational infrastructure, artistic experimentation, and institutional engagement that predated the bubble continued to evolve. Recent scholarship reveals this complexity: research demonstrates that NFT pricing is driven by aesthetic and emotional factors rather than purely speculative fundamentals (Kaur Nagpal & Renneboog, 2024), while corpus analysis of major art market reports shows NFTs achieving mainstream institutional recognition despite remaining emergent in high-end segments (Poposki, 2024). These findings suggest that the cultural significance of NFTs extends beyond their market valuations, encompassing behavioral dimensions of digital ownership and evolving institutional valorization that persist independent of speculative cycles. The present study expands on this prior research to showcase how institutions have been interacting with NFTs and blockchain artists via acquisitions, exhibitions, and residencies, while also addressing the preservation challenges that museums face in maintaining long-term access to blockchain-based artworks.

Early days (2015 - 2021)

The Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna (MAK) pioneered institutional NFT collecting in 2015 when it became the first museum to acquire an NFT for its permanent collection (Ghorashi, 2015). The purchased work, Event Listeners by Harm van den Dorpel, is a generative piece employing line-based compositions overlaid with text to explore social relations. From an edition of 100, another copy was later acquired in 2017 by The Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe (ZKM). Beyond Event Listeners, ZKM's inaugural digital collection encompassed the iconic early NFT projects CryptoPunks and CryptoKitties. In the introductory page about CryptoArt, an exhibition dedicated to NFTs that was staged by ZKM in the middle of 2021, the exhibition curators recognized how NFTs have transformed the economics of digital art by providing scarcity to the market, while also pointing to the transparent nature and immutability of blockchains (ZKM, 2021).

Ironically, while ZKM was one of the first museums to interact with blockchains and NFTs, they were also one of the first to be challenged by the sheer technical complexity and abysmal user experience that plagued these technologies (and still does to this day, although to a lesser extent), leading to the loss of two out of the four CryptoPunks owned by the museum in 2021 (Batycka, 2022).

The Whitney Museum's early engagement with NFTs demonstrates institutional recognition of blockchain technology's potential to reimagine art ownership and access models. In 2018, the museum acquired an NFT from Eve Sussman's 89 Seconds Atomized collection, in which the artist fragmented the final artist proof of her acclaimed 2004 film 89 Seconds at Alcázar into 2,304 NFTs. This 'atomization' was designed to experiment with 'shared guardianship'—a novel ownership structure wherein the complete work could be exhibited at any venue provided all NFT holders consented to the screening. Given that the Whitney already held a traditional edition of Sussman's film in its permanent collection, the museum's decision to acquire one of the fragmented NFTs represented a deliberate curatorial strategy to participate in this experimental ownership model (Overbeek, 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated museum engagement with NFTs as revenue generation tools amid widespread financial pressures. Major institutions like the Uffizi Gallery, State Hermitage Museum, and British Museum capitalized on the 2021 NFT boom by selling digital versions of masterworks from their collections, generating substantial revenue through these novel monetization strategies. However, these initiatives faced significant criticism from industry (Bailey, 2021) and academia alike (Quiñones Vilá, 2023). They also raise longstanding concerns of museums’ commercial control over digital reproductions of public-domain artworks (Petri, 2014; Garvin, 2019). The backlash against these pandemic-era commercial experiments appears to have had a lasting impact, as museums have largely refrained from similar NFT monetization tactics since the initial wave of institutional sales, suggesting that the criticism effectively deterred further exploitation of the NFT trend for revenue generation.

The beginnings of institutionalization (2022 - today)

Buffalo AKG Museum (formerly known as Albright-Knox Gallery) organized Peer to Peer in November 2022, in cooperation with the online platform Feral File. This was a major milestone for art on the blockchain as it was the first retrospective organized by an American museum dedicated to blockchain artists (Buffalo AKG Art Museum, 2022). No surprise for the trends set by the museum; according to Tina Rivers Ryan, the museum’s curator at the time of the Peer to Peer exhibition, the Albright-Knox Gallery was the first museum to dedicate an exhibition to photography in 1910. In December 2022, after the conclusion of Peer to Peer, the museum acquired all sixteen artworks that were exhibited, creating the first major collection of blockchain artists for an art museum in the United States.

Worth noting in the aforementioned acquisition is that the museum did not actually acquire NFTs, except for a piece by Simon Denny, since in all but Denny’s case the NFT was not conceptually part of the artwork and only served as documentation, says Ryan (WAC Labs, 2023). Denny’s work Metaverse Landscape 1: Decentraland Parcel -81, -17 is a conceptual piece that links a physical painting to an open edition of dynamic NFTs minted on the blockchain. Although the museum did not acquire an NFT edition for the rest of the artworks, they received 50% of the primary sales of the NFTs that were sold as part of the exhibition and will continue to receive 5% of royalties from secondary sales in perpetuity, according to the Feral File website.

Not long after Peer to Peer, in February 2023, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) struck a deal with the well-known pseudonymous collector Cozomo de’ Medici to receive a donation of 22 NFTs by 16 international artists that made LACMA the museum with the largest NFT collection in the US at the time. This acquisition by LACMA came on the back of a few other NFT acquisitions by the museum in the years prior to the Medici donation. In 2022, artist John Gerrard donated The Western Flag to the museum, followed by the estate of Lee Mullican donating ALMT28B.TGA, "Computer Joy", which Mullican developed during UCLA's Advanced Design Research Center's Program for Technology in the Art in the mid-1980s. In June 2022, Paris Hilton, well-known media personality and businesswoman, put together an acquisition fund for LACMA to acquire artworks by women artists. Through Hilton’s fund, NFTs by Krista Kim, Nancy Cahill Baker, and Shantell Martin have been added to the museum’s collection (Schwarz, 2023).

Centre Pompidou entered the NFT collecting sphere in February 2023 with a comprehensive acquisition of works by 16 artists, including French new media pioneers Claude Closky and Fred Forest alongside international figures such as Larva Labs (creators of CryptoPunks and Autoglyphs), Agnieszka Kurant, and Sarah Meyohas. The museum's curators framed this acquisition as "an original study of the ecosystem of the crypto-economy and its impact on the definitions and contours of artworks, creators, collections and the receiving public" rather than mere trend-following (Centre Pompidou, 2023). Their selection process targeted three distinct artist categories: crypto-native artists, practitioners from web design, music, or text who achieved success through blockchain technologies, and established digital artists active since the 1990s who only recently gained institutional recognition. This taxonomic approach demonstrates the museum's analytical framework for understanding NFTs within broader art historical and technological contexts.

Following its NFT foray, Centre Pompidou has systematically expanded its blockchain-based collection through strategic acquisitions. In March 2024, the museum acquired Holly Herndon and Mathew Dryhurst's AI-generated video I'm Here 17.12.2022 5:44 and Robert Alice's BLOCK 10 (52.5243° N, -0.4362° E) from his Portraits of a Mind series. The museum further acquired Anne Spalter's AI-generated video The Wonder of it All, demonstrating sustained institutional engagement with both AI-generated art and blockchain technologies (Centre Pompidou, 2024).

MoMA entered the NFT collecting landscape in October 2023 through two significant donations: Refik Anadol's Unsupervised and Ian Cheng's 3FACE (MoMA, 2023). Anadol's work employs generative artificial intelligence to interpret and transform over 200 years of art from MoMA's permanent collection, creating a recursive dialogue between the museum's historical holdings and contemporary computational processes. The piece was donated by 1OF1 and the RFC Collection. Cheng's 3FACE comprises 4,096 adaptive artworks that analyze their owners' wallet data and online behavior to generate personalized visual portraits, with four editions donated to the museum by Outland Art.

The Whitney Museum expanded its NFT collection significantly throughout 2023, beginning with the acquisition of two works from LoVid's three-part Hugs on Tape series in May. In November, the museum acquired four editions of Ian Cheng's 3FACE (also donated by Outland Art), followed by 22 editions from Frank Stella's 100-piece NFT project Geometries and an Autoglyph by Larva Labs. These acquisitions demonstrate Whitney's strategic approach to collecting across different generations of digital artists, from established figures like Stella adapting to blockchain technologies to crypto-native creators like Larva Labs.

The Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio became the first institution to host an NFT artist residency in 2023, with Osinachi serving as the inaugural digital artist-in-residence under director Adam Levine, who had previously staged numerous digital art exhibitions at the museum. According to Levine, "We had been thinking about how we could fully engage with artists who create digitally, bringing artists into our community, and going into theirs. Our goal was to treat digital art as art, and to give them the opportunity to explore their own practice and really build on this notion of community" (Christie’s, 2023). The program continued in 2024 with Yatreda, an Ethiopian family of artists who create digital works in the style of tizita—a profound sense of nostalgia and longing for the past. Their residency culminated in Abyssinian Queen, which premiered in the exhibition Ethiopia at the Crossroads dedicated to Ethiopia's cultural heritage. The museum acquired NFT works from both artists upon completion of their respective residencies.

A growing number of prominent institutions—including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of the Moving Image in New York, House of Electronic Arts (HEK) and EPFL Pavilions in Switzerland, DEJI Art Museum in Shanghai, and Castello di Rivoli—have made NFT acquisitions. Rather than cataloging every institutional adoption, this study examines a notable paradox: despite widespread media narratives declaring NFTs obsolete following the market collapse of 2021-2022, museums have continued integrating blockchain-based works into their permanent collections. This sustained institutional engagement suggests a decoupling of curatorial assessment from market speculation, as museums legitimize NFTs through acquisition practices that position these works within the evolving canon of art history.

Challenges

While museums demonstrate increasing commitment to NFT collecting, this emerging technology presents significant preservation challenges that most institutions are ill-equipped to address. These concerns extend beyond museums to affect collectors and artists—essentially any NFT stakeholder. Regina Harsanyi, Associate Curator of Media Arts at the Museum of the Moving Image (MoMI), outlined these challenges at Digital Art Mile 2024 in Basel, addressing both blockchain-specific preservation issues involving NFTs and smart contracts as well as traditional time-based media conservation concerns that compound the complexity of maintaining digital artworks.

Blockchain-related costs

Hardware

Harsanyi identifies blockchain decentralization as creating significant data redundancy challenges, noting that node operators must store "multiple terabytes and counting" of data, which she characterizes as "incredibly cost-prohibitive." However, this redundancy represents an inherent architectural feature rather than a design flaw, as the replication of blockchain data across all nodes is fundamental to maintaining decentralized consensus. While decentralization offers certain advantages for digital art preservation, it does not constitute a comprehensive solution for data storage challenges. Until technological advances enable more efficient verification methods that do not require complete data storage at each node (Ethereum.org, 2024), this redundancy remains a necessary trade-off for maintaining blockchain integrity.

Ethereum's hardware requirements for node operation are more manageable than Harsanyi's concerns might suggest. As of June 2025, running an archival node requires 2–3 TB of storage with linear scaling. Full nodes, an alternative mode of operation that removes non-essential data over time, need approximately 1.2 TB. Nodes can be configured to retain specific pruned data if artworks depend on them. With 2 TB storage costing under $100 (Bendle, 2023), the total upfront investment for an Ethereum node ranges from $700–$1,500, with monthly operating costs of $60–$120. These figures demonstrate that individual node operation remains accessible.

Software

Blockchain preservation also involves dependency on platform-specific programming languages such as Solidity for Ethereum or Michelson for Tezos. These relatively new languages possess smaller developer communities compared to established programming languages, creating potential sustainability concerns for long-term preservation. This specialization presents challenges for museum conservators, who would need to develop technical expertise in blockchain programming to maintain these works independently. Such skills become particularly critical when considering future scenarios where languages may become obsolete, requiring code migration to newer platforms—especially in cases where artists or their estates are unavailable to assist with technical updates. However, potential migrations may conflict with artist intention, necessitating that museums address these preservation scenarios during the acquisition process to establish clear protocols for maintaining artistic integrity while ensuring long-term accessibility.

(De)centralization

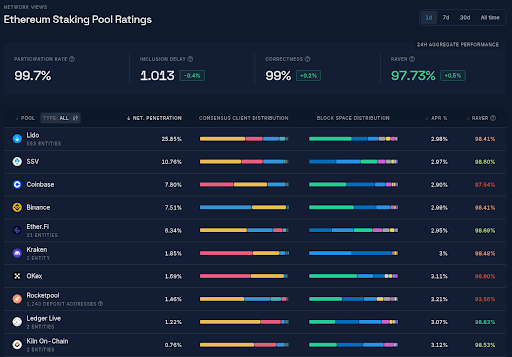

Harsanyi also raised concerns about blockchain centralization, noting that many node operators rely on centralized providers like Infura, which deploys infrastructure on Amazon Web Services rather than maintaining truly decentralized networks. While this observation accurately describes execution client infrastructure, it overlooks a crucial technical distinction in Proof of Stake networks like Ethereum. For assessing true decentralization, consensus client diversity—the software responsible for blockchain validation—proves more significant than execution client distribution. Unlike execution clients, consensus clients maintain network integrity by validating transactions and keeping participants honest. Analysis of staking node operator diversity reveals a more decentralized landscape, with the largest operator controlling less than 5% of staking nodes as seen in Figure 1. This technical nuance suggests that while infrastructure dependencies exist, the fundamental consensus mechanism remains sufficiently decentralized to maintain blockchain security and integrity.

The critical metric for evaluating network security lies in the distribution of actual ETH stake that secures the network. Entities controlling more than 33% of total stake could theoretically launch specific attacks such as transaction censorship or block finality delays, while those exceeding 51% could enable more severe exploits like double-spending. As seen in Figure 2, Lido holds approximately 26% of network stake as a community governed by the Lido DAO, followed by SSV, Coinbase, and Binance. However, these entities function as staking service providers rather than direct stakeholders, operating on behalf of clients who retain underlying ownership. This structure creates natural disincentives against malicious behavior, as attacks would undermine client confidence and threaten the providers' business models. With the largest entity holding well below the 33% threshold, current stake concentration remains within acceptable security parameters. Moreover, even if major entities could theoretically reach attack thresholds, their role as service providers operating on client assets creates strong economic disincentives against network manipulation, indicating that Ethereum's consensus mechanism maintains sufficient decentralization to resist attacks.

A comparative analysis of decentralization metrics across major NFT-supporting blockchains, including Bitcoin, Tezos, and other emerging platforms, would provide valuable insights into network security variations, though such analysis extends beyond the scope of this study.

Immutability

In a follow-up interview conducted as part of this study, Harsanyi elaborated on blockchain limitations, arguing that "when you truly understand how different blockchain protocols function, you realize that none of them are as useful as claimed. They're not genuinely immutable." She identifies three specific challenges to immutability claims: NFTs managed through admin access that can compromise permanence, certain blockchains like Flow that lack inherent immutability, and questions about whether even supposedly immutable blockchains can maintain this promise indefinitely. These technical concerns highlight the gap between blockchain marketing rhetoric and operational reality. As market participants develop greater technical literacy, a natural selection process may emerge wherein artists migrate toward more secure networks offering stronger immutability guarantees, with collectors and institutions following these preferences. This evolution toward technically informed decision-making could ultimately drive the NFT ecosystem toward more robust and genuinely decentralized platforms.

Is the blockchain truly forever?

Adjacent to decentralization and immutability concerns is the question of blockchain network longevity. Developers must ensure that current infrastructure remains operational long-term, with contingency plans for network discontinuation that preserve artwork functionality. Potential solutions include deploying final network states in read-only mode or migrating works to alternative networks, though migration depends on artwork portability and absence of network-specific dependencies that cannot be replicated elsewhere. However, blockchain cessation represents primarily a social rather than technical challenge, creating significant implications for artwork functionality. Even works requiring continuous block production could theoretically be preserved through museum-operated nodes functioning independently of broader network participation, though such isolated operation may conflict with artists' original intentions. These scenarios underscore the necessity for museums to engage proactively with artists during acquisition, establishing clear preservation protocols that balance technical feasibility with artistic integrity while planning for various network lifecycle contingencies.

Where does the content live?

NFTs typically rely on an architectural separation between on-chain and off-chain components: the blockchain stores a reference pointer (such as a URI or a content identifier), while the actual content—images, videos, or metadata—resides externally on platforms like IPFS, Arweave, or traditional web servers (Wang et al., 2022; Balduf et al., 2022). This design introduces critical complexities: NFT owners face ongoing responsibilities to ensure the persistent availability of their assets at these off-chain locations, as even decentralized storage solutions can suffer from node churn and incomplete data replication (Balduf et al., 2022; Salem & Mazzara, 2024). Notably, studies have highlighted that approximately 21% of NFT metadata links are either broken or point to duplicate or inaccessible resources (Wang et al., 2022).

Given these challenges, it is imperative that artists, collectors, and their estates retain the ability to update or redirect these off-chain references within NFT smart contracts. This flexibility would mitigate the risk of digital asset decay and ensure sustainable long-term management of NFTs (Salem & Mazzara, 2024). Such governance mechanisms are crucial not only for preserving cultural and economic value but also for supporting the authenticity and provenance claims that underpin NFT markets.

Security

Multi-signature wallets ('multisigs') are specialized blockchain accounts requiring authorization from multiple designated parties before asset transfers, providing enhanced security and governance compared to standard single-signature accounts (Antonopoulos, 2015). Analysis of Ethereum accounts belonging to major NFT-collecting institutions reveals that nearly all museums operate single-signature wallets, with Centre Pompidou representing the sole exception utilizing multisig security. This finding emerges from examination of accounts associated with Castello di Rivoli, Centre Pompidou, LACMA, MAK Vienna, MoMA, MoMI, Toledo Museum of Art, Whitney Museum, and ZKM. The prevalence of single-signature configurations creates potential security vulnerabilities, as any compromise of the controlling device could result in complete asset loss. While many institutions likely employ hardware wallets to mitigate such risks, this security measure cannot be verified through public blockchain data, highlighting a gap between recommended security practices and institutional implementation in the museum sector.

Time-based media art challenges

Beyond the inherent complexities posed by blockchain technology, the conservation of time-based media art presents its own set of challenges (Barok et al., 2019; Engel & Wharton, 2017). These include the ongoing upkeep required to ensure that artworks remain functional and accessible; the need to maintain compatibility with contemporary computer systems despite rapid technological obsolescence; as well as considerations around hardware material usage, electricity consumption, and the environmental impact of digital infrastructures (Harsanyi, 2024). According to Harsanyi, most museums lack the dedicated resources, expertise, and technical frameworks necessary to effectively address these challenges, leaving significant gaps in digital preservation strategies.

During her talk at the Digital Art Mile 2024, Harsanyi detailed MoMI’s digital artwork acquisition process. She outlined the museum’s approach to assessing long-term viability, ensuring that artworks can be migrated or emulated as technology evolves, and developing sustainable practices that account for energy and material consumption. These insights underscore the need for holistic, institution-wide strategies to conserve digital art beyond the blockchain, bridging technical, curatorial, and infrastructural considerations to secure cultural heritage in the digital era.

Pre-acquisition considerations

Prior to acquisition, conservators must thoroughly understand the technical underpinnings of the artwork, including its software dependencies, programming languages, and the potential ease—or difficulty—of long-term maintenance (Harsanyi, 2024). This technical literacy is crucial for developing informed strategies for ongoing preservation, migration, or emulation as systems evolve. In the case of MoMI, for example, a Submission Information Package (SIP) from the artist or previous owner is expected to contain not only the digital artwork itself but also a checksum—a cryptographic identifier that verifies data integrity—alongside comprehensive supplemental documentation, including images and other metadata that contextualize the work (Harsanyi, 2024). Such documentation ensures that curators and conservators possess the necessary information to manage the artwork’s authenticity, functionality, and cultural value over time.

Artist consultation

A thorough technical questionnaire and an in-depth interview with the artist are essential components of the acquisition process. These steps help conservators understand the artist’s display preferences and intentions, including whether aspects such as orientation, resolution, or format flexibility are acceptable or integral to the artwork’s identity (Harsanyi, 2024). Engaging directly with the artist in this way allows institutions to document critical information about the work’s conceptual and technical requirements, which, in turn, guides future preservation decisions and ensures that the artist’s vision is respected even as technologies evolve.

Archival practices

Once acquired, the digital artwork must be meticulously archived to ensure its long-term preservation and accessibility. At MoMI, this process involves creating an Archival Information Package (AIP), in which all files undergo checksum validation to confirm their integrity (Harsanyi, 2024). Data is then stored on a Redundant Array of Independent Disks (RAID) system to protect against hardware failure, with offsite backups maintained in separate geographic locations to mitigate risks of local disasters or infrastructure loss. In addition to these digital safeguards, a magnetic tape backup—typically Linear Tape-Open (LTO)—is employed as a non-digital archival solution, which conservators replace every three to five years to prevent data degradation (Harsanyi, 2024). Annual audits of the AIP, including checksum revalidation and bit-level integrity checks, further ensure the artwork’s stability over time. This multi-layered approach exemplifies best practices in digital preservation, addressing both technological and environmental vulnerabilities inherent in time-based media art.

Institutional capacity

Few museums possess the necessary resources to adequately preserve time-based media art, which demands not only specialized conservators but also robust information technology departments and infrastructure capable of managing complex digital objects (Barok et al., 2019; Harsanyi, 2024). The availability of trained time-based media conservators remains limited, and many institutions struggle to build and sustain the requisite expertise internally. Pre-acquisition protocols—including comprehensive technical assessments and risk analyses—are critical to ensuring the long-term viability of digital works. Yet, according to Harsanyi (2024), even major museums often neglect to conduct such protocols systematically, leaving significant gaps in preservation planning and potentially undermining the sustainability of their digital collections.

NFT relevance

Harsanyi (2024), along with the Buffalo AKG Museum case—where, as part of the Peer to Peer exhibition, the museum consciously chose not to acquire NFTs as certificates of authenticity—underscores the importance of museums understanding the total cost of ownership for digital artworks. This consideration encompasses not only acquisition expenses but also the ongoing technical maintenance required to sustain these works over time. A holistic perspective is essential for effective stewardship, ensuring that digital artworks remain accessible and functional in the long term.

Furthermore, the relationship between blockchain-based artworks and NFTs warrants careful consideration. While NFTs often serve merely as digital receipts that reference a particular work, they are rarely integral to the artwork’s concept or display (Wang et al., 2022; Balduf et al., 2022). Museums should explicitly clarify with artists whether an NFT holds conceptual significance, particularly when the token itself does not contain essential aspects of the artwork’s media, behavior, or experience.

Such clarification helps museums streamline their collections and avoid unnecessary technical complexity. However, it also carries potential reputational risks for both the artist and the institution. For example, if an artist previously sold an NFT and later downplays its significance when approached by a museum, this inconsistency could be perceived as contradictory and might provoke backlash from collectors who initially purchased the NFT as an authentic part of the artwork’s value. These challenges highlight the delicate balance institutions must strike in managing digital art acquisitions while maintaining transparency and trust with artists and collectors alike.

Conclusion

The institutional art world’s increasing engagement with blockchain technology is undeniable, providing both validation for digital creators and new avenues for established institutions to evolve their practices. Museums are actively incorporating blockchain-based artworks into their programming and collections, reflecting a broader commitment to embracing emerging digital mediums. Various initiatives—including exhibitions, commissions, and artist residencies—illustrate how institutions are reimagining traditional collecting paradigms to remain relevant within the rapidly evolving contemporary art landscape.

However, this transformation is not without significant challenges. Museums and collectors must navigate the technological complexities introduced by blockchains while addressing the inherent conservation issues surrounding time-based media art. The preservation of digital works requires a systematic approach to documentation, storage, and display that many institutions are still unaware of. Additionally, questions around ownership, provenance, and the relationship between physical and digital manifestations of artwork continue to evolve.

The future of blockchains and NFTs in the art world will likely be shaped by those who can thoughtfully bridge the current gaps — embracing technological innovation while honoring artistic intent and ever-evolving collecting values. As artists, museums, and other market participants continue to explore these digital frontiers, their success will depend on developing robust strategies that encompass both technological understanding and artistic vision, ensuring that blockchain-based art fulfills its potential as a significant chapter in art history rather than a passing technological curiosity.

References

Alice, R. (2024). Exclusive: Robert Alice work acquired by Pompidou in advance of Christie’s auction. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://www.robertalice.com/press/exclusive-robert-alice-work-acquired-by-pompidou-in-advance-of-christies-auction

Antonopoulos, A. M. (2017). Mastering Bitcoin: Unlocking digital cryptocurrencies (2nd ed., pp. 121–127). O’Reilly Media.

Bailey, J. (2021). Why museums should be thinking longer term about NFTs. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://www.artnome.com/news/2021/7/28/why-museums-should-be-thinking-longer-term-about-nfts

Balduf, L., Florian, M., & Scheuermann, B. (2022). Dude, where’s my NFT? Distributed infrastructures for digital art. Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference. https://doi.org/10.1145/3565383.3566106

Barok, D., Boschat Thorez, J., Dekker, A., Gauthier, D., & Roeck, C. (2019). Archiving complex digital artworks. Journal of the Institute of Conservation, 42(2), 94–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/19455224.2019.1604398

Batycka, D. (2022). Into the ether: How a German museum accidentally lost access to two highly valuable NFTs. The Art Newspaper. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/01/21/a-german-museum-has-accidentally-lost-access-to-two-highly-valuable-nfts

Bendle, S. (2023). SSD price index 2024: Cheapest price on 1TB, 2TB and 4TB models. Tom’s Hardware. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://www.tomshardware.com/news/lowest-ssd-prices

Buffalo AKG Art Museum. (2022). Peer to Peer exhibition. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://buffaloakg.org/art/exhibitions/peer-peer

Centre Pompidou. (2023). The Centre Pompidou in the age of NFTs. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://www.centrepompidou.fr/en/magazine/article/le-centre-pompidou-passe-a-lheure-nft

Centre Pompidou. (2023). The Wonder of it All. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://www.centrepompidou.fr/en/ressources/oeuvre/yfVtGc4

Christie’s. (2023). Osinachi is rewriting art history at the Toledo Museum. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://www.christies.com/en/stories/osinachi-at-the-toledo-museum-of-art-0948941366f24ef19c9d11739ebda421

Engel, D., & Wharton, G. (2017). Managing contemporary art documentation in museums and special collections. Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, 36(2), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1086/694245

Ethereum.org. (2024). Statelessness, state expiry and history expiry. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://ethereum.org/en/roadmap/statelessness/

Ghorashi, H. (2015). MAK Vienna becomes first museum to use Bitcoin to acquire art, a Harm van den Dorpel. ARTnews. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://www.artnews.com/art-news/market/mak-vienna-becomes-first-museum-to-acquire-art-using-bitcoin-a-harm-van-den-dorpel-3995/

Hawkins, J. (2023). Are NFTs really dead and buried? All signs point to ‘yes’. The Conversation. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from http://theconversation.com/are-nfts-really-dead-and-buried-all-signs-point-to-yes-214145

Kaur Nagpal, G., & Renneboog, L. (2024). Passion for pixels: Affective influences in the NFT digital art market. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5030330

Klee, M. (2023). Your NFTs are actually—finally—totally worthless. Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/nfts-worthless-researchers-find-1234828767/

Liscia, V. D. (2021). “First ever NFT” sells for $1.4 million. Hyperallergic. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from http://hyperallergic.com/652671/kevin-mccoy-quantum-first-nft-created-sells-at-sothebys-for-over-one-million/

MoMA. (2023). MoMA announces groundbreaking new digital art acquisitions, exhibitions, and artist collaborations. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://press.moma.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/MoMADigitalArtAnnouncements_FINAL-2.pdf

Overbeek, A. (2022). Screen time: How museums are thinking about NFTs. Gagosian Quarterly. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://gagosian.com/quarterly/2022/08/17/essay-screen-time-how-museums-are-thinking-about-nfts/

Petri, G. (2014). The public domain vs. the museum: The limits of copyright and reproductions of two-dimensional works of art. Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, 12(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.5334/jcms.1020054

Poposki, Z. (2024). Corpus-based critical discourse analysis of NFT art within mainstream art-market discourse and implications for the political economy of digital art. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1296. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03827-3

Quiñones Vilá, C. S. (2023). A Brave New World: Maneuvering the Post-Digital Art Market. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12060240

Salem, H., & Mazzara, M. (2024). Hidden risks: The centralization of NFT metadata and what it means for the market. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.13281. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.13281

Schwarz, G. (2023). Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Outland. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://outland.art/los-angeles-county-museum-of-art/

Wac Labs. (2023). Who holds the keys? The issues with putting NFTs in the museum collection. Medium. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://medium.com/@wac-lab/who-holds-the-keys-the-issues-with-putting-nfts-in-the-museum-collection-f41ddc5d6150

Wang, Z., Gao, J., & Wei, X. (2022). Do NFTs’ owners really possess their assets? A first look at the NFT-to-asset connection fragility. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.11181. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2212.11181

ZKM. (2024). CryptoArt. Retrieved June 8, 2025, from https://zkm.de/en/exhibition/2021/04/cryptoart