In this article, you can find my thoughts on how the VC game is broken and why it happened, split into three sections:

-

Peter Pan and VC Neverland

-

The mirage of dry powder

-

Bonus: what I want to remember for the next bull run

Originally posted here 02.02.2023

TLDR;

-

The last decade in venture capital has been favorable with cheap money and clear trends, creating a wide open field for investors to do well as long as they are investing in similar areas as their friends.

-

Investing appears to have become an exercise in optimizing dollars at work in the “best” companies and management fees than optimizing returns from carry, but the industry and its returns have been too long playing main characters in a Peter Pan movie and some things just have to crack.

-

VC investing became a very strange competition. If VCs should be investing in things that are crazy and unlikely to work, it would make sense if founders would find it more challenging to encourage investors to put money into their idea instead of investors kindly approaching founders to take their money into the round.

-

The bigger the fund, the higher the management fees, and the less incentive to actually do deals because the fee income is just too good. Doing deals and making returns is a lot more work and risk.

-

Life revealed that a lot of the great investments have been just numbers in excel.

-

Successful seed investors are planning to invest as usual, just looking for lower valuations. Established growth investors are mostly sitting on their hands (and this is already visible in charts).

-

All of this happens slowly because while public markets trade daily and prices then adjust instantly, private markets don’t get reset until follow-on financing rounds happen which can take 6–24 months.

Ok, then let’s begin the journey!

Peter Pan and VC Neverland

The last decade in venture capital was incredibly favorable with cheap money and clear trends. This created a wide-open field for investors, as long as they were investing in similar areas, they were likely to do well given the favorable conditions. Many individuals did extremely well, becoming wealthy and generating wealth for those around them. However, some may have confused their luck for success. Venture capital was seen as an attractive industry due to the potential for high returns and limited risk. In the end, everybody is winning in Neverland, right?

In the older days, the takeaway for investors was that the best returns come from betting on things that seem unlikely to work and then turn out to be right in doing so. Did you put your money into crypto early? You are good now. Have you done that with the cloud? You made it. But it doesn’t take to be very deep into the topic to make a conclusion that recent investing appears to have become an exercise in optimizing dollars at work in the “best” companies & management fees than optimizing returns from carry. I believe it will all change soon. The industry and its returns have been too long playing main characters in the Peter Pan movie and some things just have to crack.

Even though I entered this space quite recently I was able to realize some things are just looking wrong. I believe we are at the point when everyone understands the trends in the space and develops a conviction that due to his high intelligence, great gut feeling, and deep understanding of underlying tech & masses behavior, is able to ride those trends. The problem is that everybody around also got such conviction and then the only thing to do is to somehow rip out a share of the pie.

For me seems all folks in the game just want to bet on the same things. If Uniswap became a great success, let’s fund all of the DEXes around there, even if there is no real product improvement (and for sure not 10x better, so users will jump to a new tool). You don’t need to even take care of the UX, not many people at the fund actually gonna check how hard it is to use your product — crypto users behave like a religious cult and will use it anyway, and if AnumberZ is investing we want it in the portfolio too!

Then while everybody “knows” what is the next hot thing in space and where the money can be made, competition begins, but a very strange one. As if VCs should be investing in things that are crazy and unlikely to work, as stated before, it would make sense if founders would find it challenging to encourage investors to put money into their idea. However, we ended up with investors kindly approaching founders to take their money into the round. At this point it was very easy for me to think that investing is just building a network, so your friends will let you put money into their endeavors, growing the economy seemed to be so easy!

Before the flood, I very often heard things like “damn, you know, we didn’t make it. As always whole allocation went to <put big US fund name with “rockstar” lineup [whatever it means] here>”. I realized that the game I see is based on taking consensus-driven takes (most of the VCs investing in products similar to those which proved to have traction and aren’t any breath of the fresh air) than taking risks and trying to make non-consensus bets with asymmetric payouts (which could be investing in Uniswap before it popped-out or anything looking like a crazy idea).

What I have seen was all chasing the same opportunities. Then the only way to make it, I found in becoming an incredibly large firm to drive out alpha. But this didn’t sound like investing in risk! I wanted to become a new Columbus entering VC and what I saw was a landscape where it makes more sense to optimize fund size and try to index the market. Even worse I realized it’s not just crypto, everything becomes consensus driven very quickly (check out current AI mania).

I think what happened is that over the last decade or even more, the winners in tech (for seed investors) got enormously huge, and basis points put into the right deal could make an investor a billionaire. So even placing plenty of seed bets wrongly, one winner could still turn the portfolio into a massive success. That has led to attracting tons of rational money into playing at casinos and took away the requirements to have nearly any judgment or skill when it came to evaluating early-stage businesses while investing. All it took was being close enough to the “disruptive tech” and getting a good enough network to get into “the good deals”. Even more, the fire has been stoked by startup factories called incubators (starting with Y combinator success — not surprisingly actually, while the survival rate of Y companies is slightly bigger than 50% which is a great, great success) which pomped out a big amount of reasonable looking “shots on goal” regardless of the actual traction of the business and product market fit.

Entrepreneurs also got better at building companies and showing them as a great opportunity. During boom years in tech, we could have seen a large number of entrepreneurs who had “been there and done that”, and that also gave them and their new ideas a lot of credibilities. Along the way, they realized they could raise capital at increasingly higher valuations because of the rising VC competition and leveraging their experience.

And in the end…life revealed that a lot of the sure bets just have been numbers in Excel. But more on that I will be able to write when I spend more time thinking about how companies are evaluated. But Chamath Palihapitiya can provide you with a pretty funny introduction to the topic.

The incentives are driving the outcome. As most of the funds are operating in 2% management fee (over up to 10 years, but in crypto it can be a much shorter period of time) and 20% carry (which means a 20% cut for money managers on profit made by VC firm) while the market became much more competitive VCs found a new way to make a good living (valuable to add here is that money in VCs hands is coming from LPs — other investors, much wealthier then actual rockstars operating the funds in most of the times. This money is coming from family offices mostly [in the EU] and mutual/pension funds [in the US]). So while more and more LPs found it interesting to put their money into the VC game, bigger and bigger funds were raised around the globe. But looking at the power law in venture capital — the incentive rather couldn’t be driving bigger outcomes, as it’s hard to scale a VC firm and it’s much harder to return with a good % billion dollar fund than the few million one.

Another narrative that appeals to me very much is that money managers (GPs) due to the great success of winners in cloud/crypto and any other seed-investing sphere changed their incentive from getting money from driving market-outstanding outcomes (so placing not-consensus-driven, crazy bets which somehow will happen to be right and get their cut on the profit of the investments) to living from big management fees and launching several new funds.

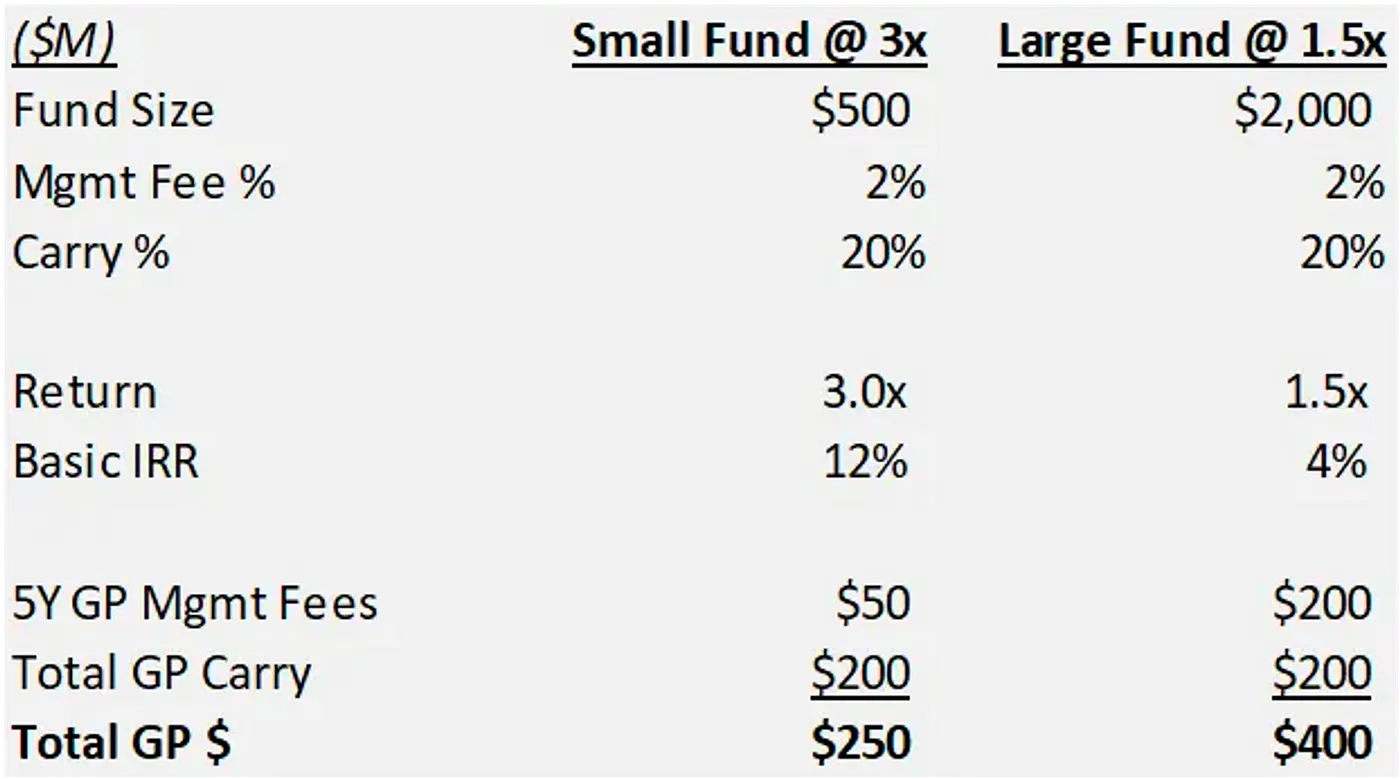

Good visualization of what I found in this article, which has been great food for my thought process and I encourage you to read it as is just a more clear (and focused on broad tech) version of my article.

Above you can see an example of how much GPs can earn in two scenarios. Within small funds, they have to make 3x return on their investment, and in the end, it will pay them out $250m. In the large fund however, they have to return only 1.5x on the investment (which will be much easier than 3x and with great circumstances can be made by indexing the market) to get the same carry, but due to much more money they operate, they will take four times bigger management fees, less risk but more reward (but not for the LPs). The large fund seems like a good business then.

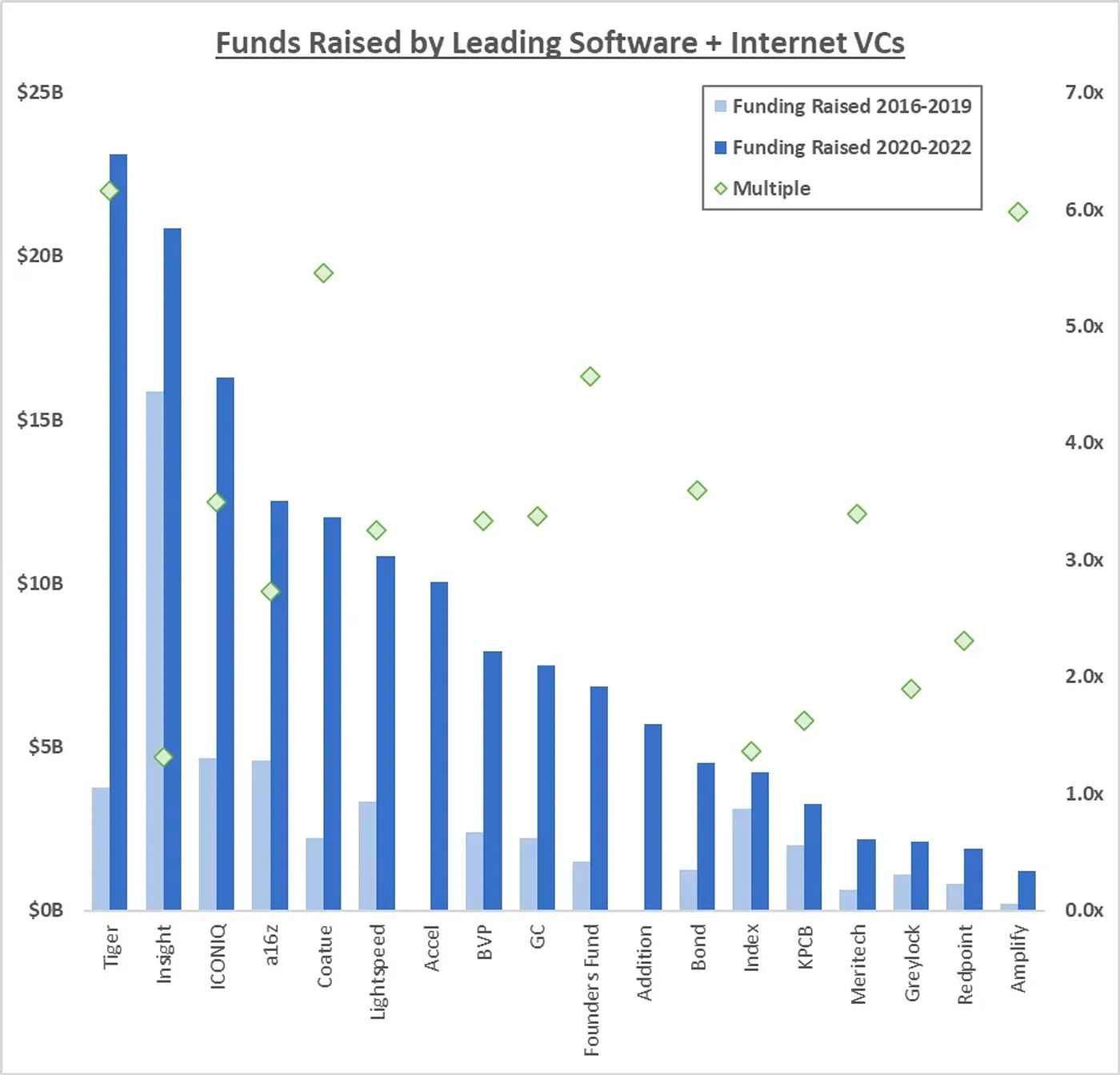

Here you can see leading funds in software and how much money they raised from LPs to manage in two recent periods. The last one (2020–2022) seems like they would new that the top of the market is near and the best way to secure themselves is to raise bigger funds...but who knows.

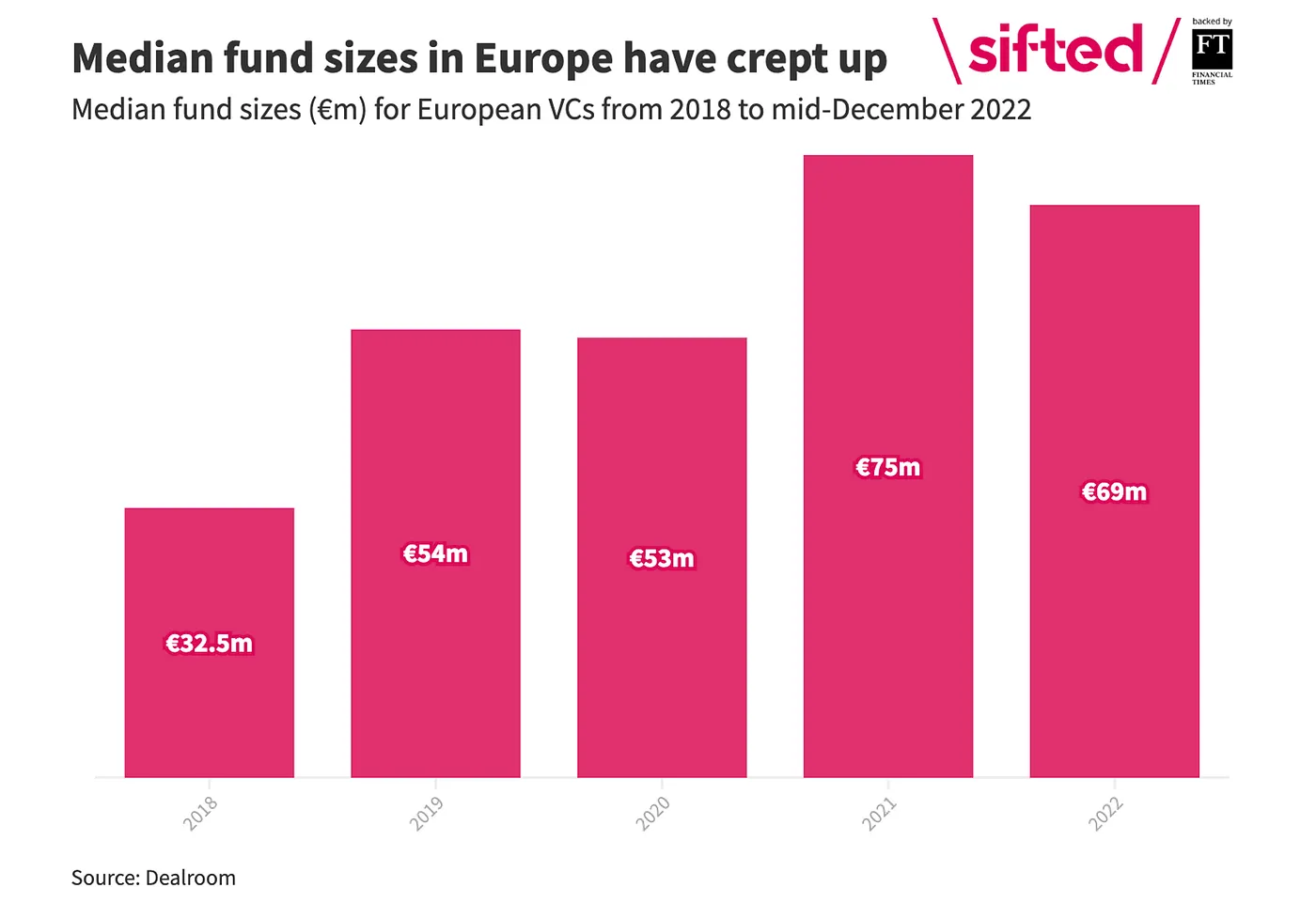

As most of the funds in the second graph are from the US, here you can see a graphic representing a similar approach taken by European VCs.

Although the above structure is a simplified version, many companies are operating in this manner. For example, if a firm has a $100 million fund, and one of its 20 portfolio companies is sold for $1.5 billion, the firm’s 20% stake in that company would be worth $300 million. However, after accounting for management fees and carry, the firm would still not be able to return 3 times the investment to its investors. With a $1 billion fund, it would be even more difficult to reach that level of return, as one or several of the 20 portfolio companies would need to have a very large exit. But after all, by definition of their size, large funds have convinced other investors regarding their skill and that they are capable of making great returns, this is social proof (with not a lot of math involved).

It’s great to add here for the defense of very large funds that small funds may lack the necessary capital to increase their stake in successful companies as they bring on additional shareholders. This is why some early-stage funds are now raising capital specifically for follow-on investments.

My take is that the venture capital industry is evolving into an indexing strategy unless it starts taking on new risks and exploring new sectors. Sad to say, a big part of crypto VCs also have to update. Some firms are doing this by managing fund size growth, but many are not. This is leading to a situation where venture capital firms are having too much access to capital, which can lead to poor allocation decisions and lower returns. The industry is subject to capital cycles like any other, so the question is about which firms can adapt, evolve, and deploy capital responsibly, rather than relying on past success until it no longer works.

The (increasingly false) truism and guiding principle that “you simply had to invest in the best companies in software / internet to generate great, outsized returns” has passed. Returns won’t come as easily as they did these past 12+ years and, as it turns out, entry price DOES matter. Alpha in traditional VC is turning to beta. Barring a few trillion dollar outcomes in AI, Neverland may never be the same.

source: https://bullfight.substack.com/p/peter-pan-and-neverland-vc-returns

The mirage of dry powder

And this way we come to the place where there is an enormous amount of money, waiting in the hands of VCs to be deployed. But is it so sure that this dry powder has to be used right now?

As the market cools down, investors will become more selective, focusing on the most successful and in-demand companies. With large amounts of capital to invest, investors will compete to put money into a limited number of top-performing businesses, leaving many lower-tier companies without funding. This will maintain artificially high valuations and lower returns for investors, as they are forced to invest in a small pool of highly sought-after companies. This mismatch between the amount of capital available and the limited number of successful outcomes will likely lead to a decline in returns.

Even more, to say this dry powder doesn’t belong to VCs, it belongs to LPs (actual investors in venture capital firms as I stated before), and in such market circumstances they won’t necessarily put pressure on VCs to invest. It can be even quite the opposite.

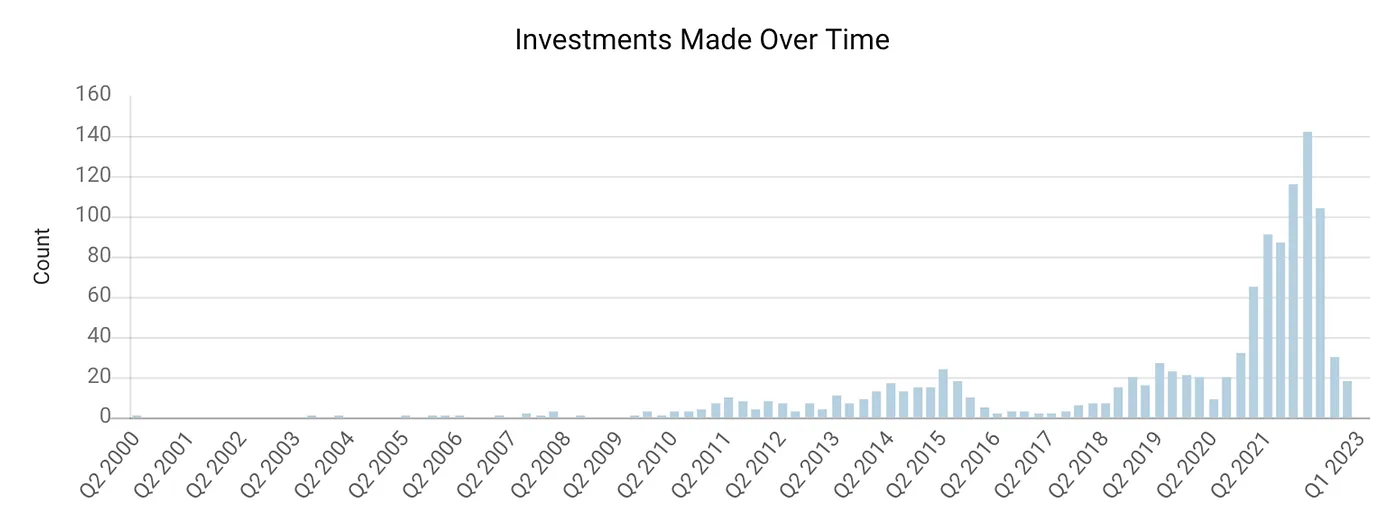

2022 was marked by stark contrast — it began with a continuation of the thriving startup scene and crazy pace of minting unicorns from the previous year, but by the end of Q1, this optimism came to a halt. As the year progressed, opportunities for growth and funding became scarce. The situation has not improved much in 2023, but there is a sense (and seems like a need, as well as hope stoked by chatGPT) of stabilization.

This can lead to:

-

successful seed investors planning to invest, as usual, just looking for lower valuations,

-

successful, established growth investors are mostly sitting on their hands (and this is already visible in charts),

-

new/average seed investors can’t raise another fund,

-

all strange creations like random SPVs, Tiger’s deal-of-the-day, “Softbank mega fund pouring money into what” will disappear.

So in 2023, it seems that while there is a significant amount of available capital in venture, there is currently no pressure to invest it. This is because venture capital firms have their own investors who have already committed a lot of capital to venture and are now suggesting that VCs slow down their investments. Additionally, LPs are concerned about the amount of cash that will be called by VCs and want the pace of investment to slow down. This means that while the availability of capital may seem promising, it may not result in increased investment opportunities for startups in the short term. It is likely that this trend will change in the future, but not until later in 2023 at the earliest.

All of this happens slowly because while public markets trade daily and prices then adjust instantly, private markets don’t get reset until follow-on financing rounds happen which can take 6–24 months.

P.S.

Overall the businesses that won’t achieve immediate success but instead will take the time to develop proprietary technology and attract only a few strong competitors will probably have the potential to deliver more value in the long run. By raising less capital, the investors and founders will be able to avoid excessive dilution. The investors plan to remain patient and hold onto their ownership in such businesses, as they believe the potential for greater returns is higher. However, it should be noted that some founders may prioritize their own gains over the long-term success of the company, potentially leaving other shareholders with worthless stock (Adam N. case, wdyt reader?).

Bonus: what I want to remember for the next bull run

As a bonus for those who made it so far and for me as a reminder to not lose my head in the next crazy ride, which someday will for sure come I prepared short lists of things I want to remember to stay sober, while all others will be opening champagne bottles.

-

When a company is trading >100x revenue and beyond, it’s probably a pretty good time to exit (if your crypto is 100x and there is actually no revenue IT’S FOR SURE A GOOD TIME TO EXIT BRO).

-

When (investing will become fun) investing will be seen as risk-free again when I can see “investors” on Tik-Tok when my Twitter feed will be much more about the “great opportunity” than memes and thoughts of my friends and great thinkers when most people won’t bother to ask why things are this way when I’ll feel like significant wealth is just one good trade away when the prices can only go up. When more folks like me will like to try to become a VC, THIS IS A GOOD TIME TO EXIT.

-

When private deals will become priced, not valued, THIS IS A GOOD TIME TO EXIT.

-

When “who” will matter more than “what”, “how” or “why”, THIS IS A GOOD TIME TO EXIT.

-

When some firms will outsource their dd, THIS IS A GOOD TIME TO EXIT.

-

When corporate finance will go out the window, THIS IS A GOOD TIME TO EXIT.

Thank you for reading!

If you’ve come this far — thank you! I assume it means you found this article interesting. I would really appreciate it if you can share it and let me know your thoughts on the topic in the comment.

Also, there are more things I share online and you can find them here:

-

Twitter, is the main source of my brain dump.

-

Lightnode Podcast, where I talk to web3 people (mostly VCs). Apple Podcast link here, and Spotify link here.

Bibliography

Sources I mentioned in the article:

There was much more on the way to make me write this, but I haven’t saved them. However, I would feel guilty if I would not mention the reads above and you can find the most alpha right there.

Also highly encourage you to read:

And to start learning how to evaluate a business you can try this (and later on actually start to study):