Brady Walker: So okay. Back to it. collaborating with strangers, you guys were randomly paired up, you Didn't choose each other. It was chosen for you. Tell me about this process and getting to know each other and trying to figure out what to do.

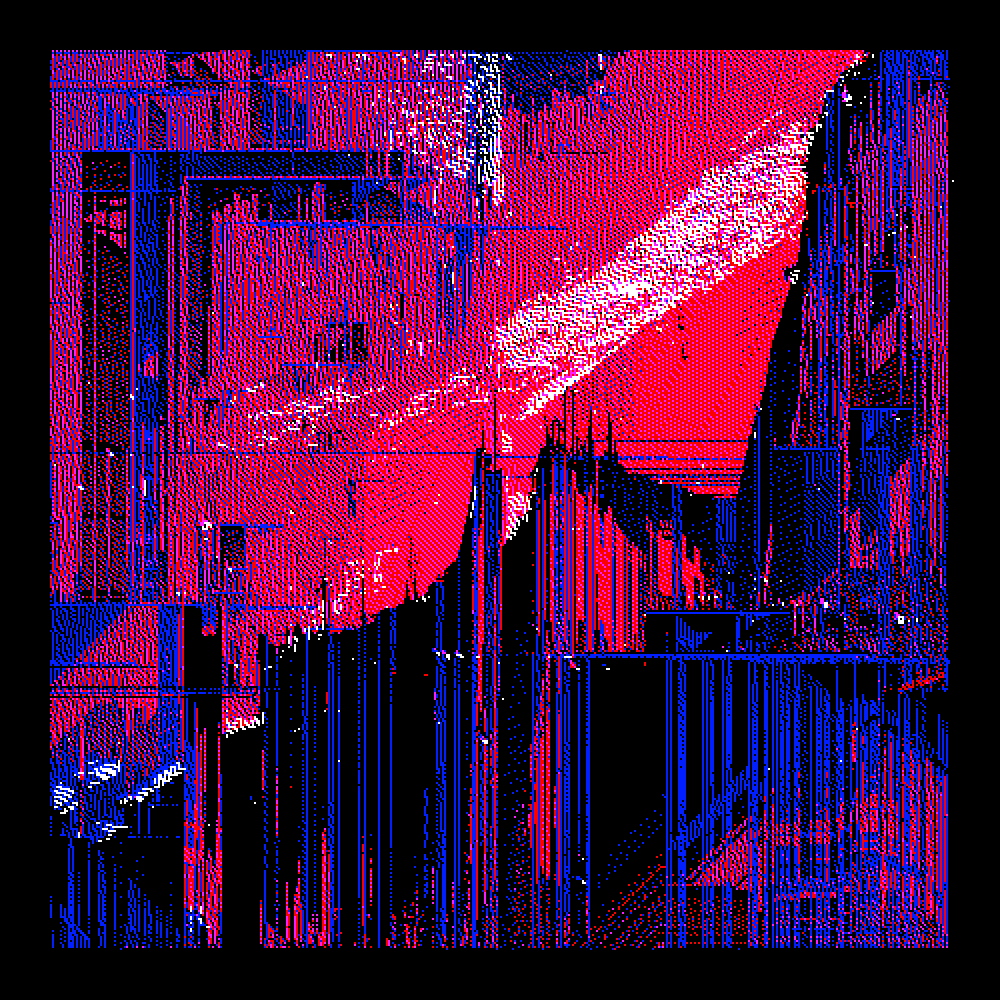

Luka Piškorec: As soon as GlitchForge came up, I got acquainted with the platform over Twitter. I was very impressed with the tech because I was already quite familiar with everything else on Tezos, and I found Glitch Forge is quite cool. I got quite fired up and then started talking more with the guys there. Even though I didn't do glitch art before, I did work with shaders and dithering and so on. So, I got quite obsessed with that. Then I just said I would like to work on something for the platform.

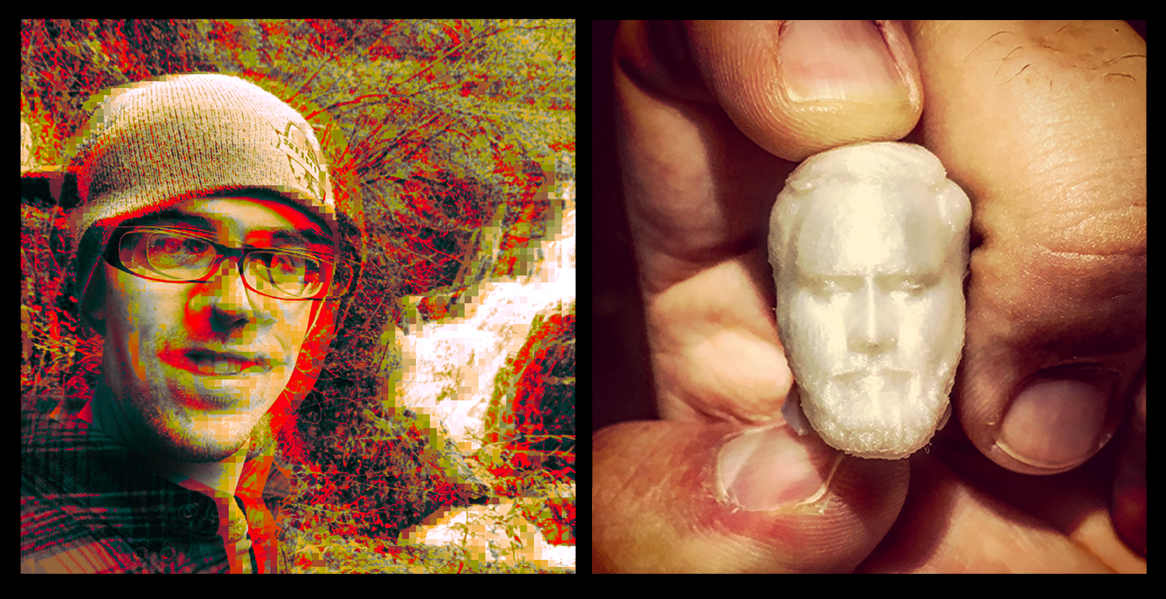

Somebody suggested I should collaborate with Jarid, and I was on board. So that's kind of how it started. It was all basically done over Discord. The initial idea was that we can sort of leverage our different skill sets and split the work to image generation and generative post-processing and glitching.

I think most coders would say that it's a challenge to collaborate on code with somebody else because it is quite a custom process. But, if you manage to pair up in this way, using different skill sets, like image production and post-processing, I think the collaboration can be quite productive.

Though I have to say I did, in a way, collaborate on the code with the Glitch Forge developer, who I think is quite a pro coder because pro coders can collaborate with somebody who is maybe a bit on a lower level than them. He would optimize my code, we would ping-pong Github pull/push requests, and it worked great, I enjoyed it and learned a lot along the way.

Brady Walker: Jarid. What was it like for you making images that you knew would be glitched? You're usually the glitch artist taking somebody else's images, but this time you were in charge of making the images that would be glitched by somebody else.

Jarid Scott: It was a lot of fun. It was a very different experience for me. Generative art has always been something that's fascinated me but I know nothing about coding. So I always kind of wrote it off as like, Oh, that's something I'll always be able to appreciate from like the viewer side of things. I probably won't be on the creation side of things. And I know I had very little to do with the actual generative aspects of this other, than, feeding source imagery. But it's really cool to be part of it.

To Luka’s point, the platform that sgt_slaughtermelon and Tartaria Archivist and the developers at Glitch Forge came up with is genius because they really are doing the hard work of finding really good coders and really good visual artists and pairing them together to make something that no one has ever seen before.

Slaughtermelon and I go way back. So he was telling me all about Glitch Forge before it came out. He was really inspired coming off of his big ArtBlocks release, which for him was kind of like the V1 or V0 of this. He's got a little bit of coding experience, but he's mostly visual artist. And his big ArtBlocks release was very much so that him in a coder teaming up to release his Auto Rad series. And they took that energy and brought it over to Tezos.

In the early days, he was like, I want to get you on Glitch Forge. Don't worry. We'll find you a coder.

My particular flavor of glitching is very much informed by this amazing artist named Kim Asendorf. He wrote this ASDF pixel-sorting code way back in the day that everyone uses, and it's amazing. The developer was trying to figure out a way to get ASDF in real time onto Glitch Forge. It was looking like it would be a lot of work. Then Luka came onto the scene.

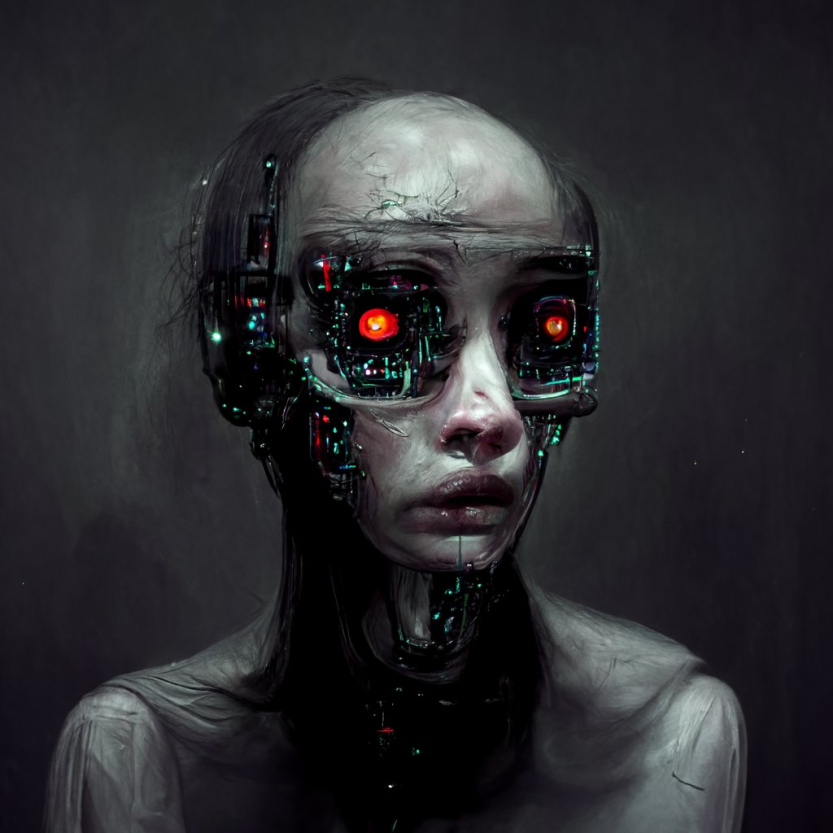

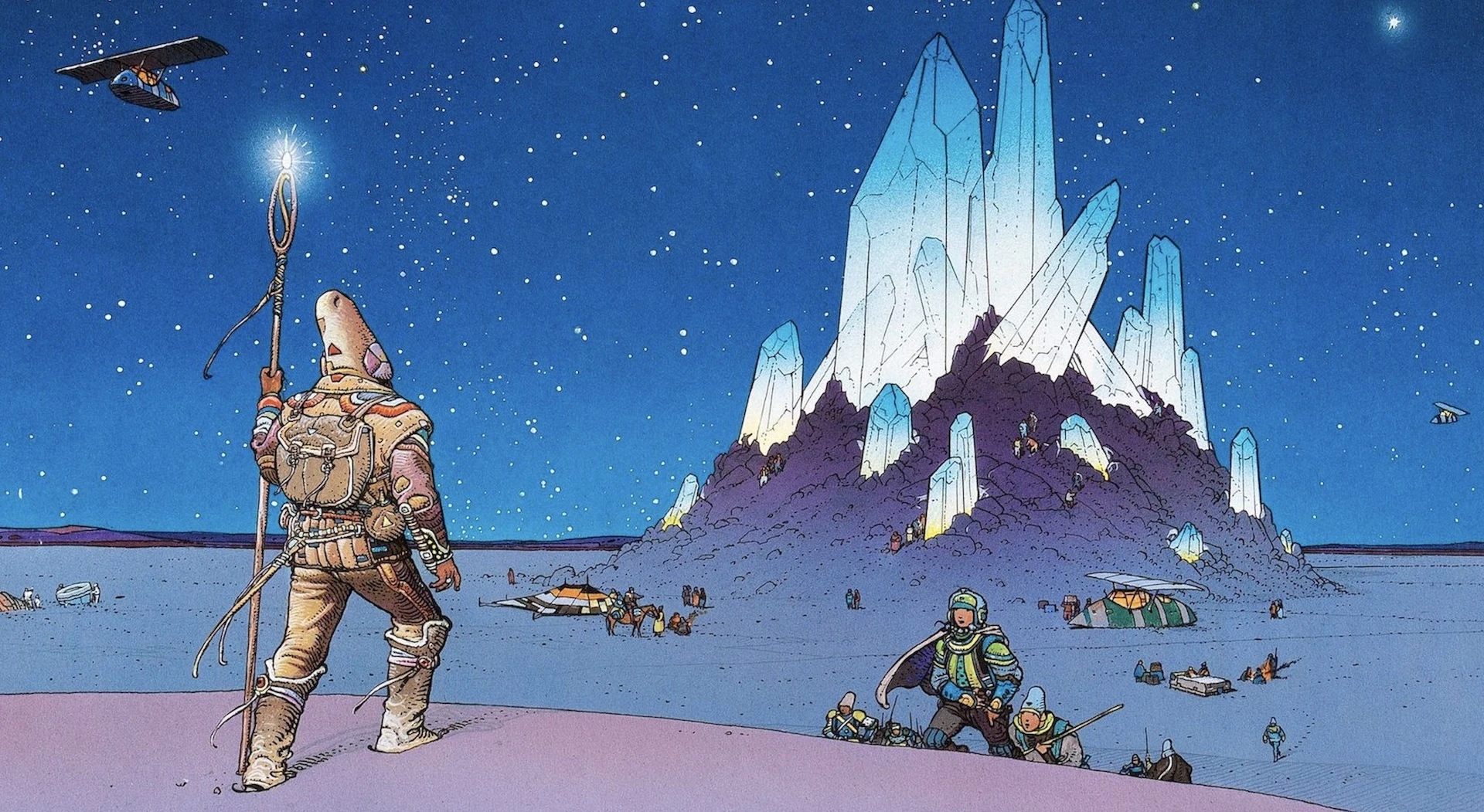

So after that, the question was, well, should I make an image for this? I have a lot of glitched imagery that I’ve already done, but then we’d be glitching already-glitched stuff, which would probably be a bit too noisy. But right around that time was when this big Midjourney/AI fascination explosion came up. And I'm working on this weird little sci-fi story project, and I've generated thousands of kind of like this concept art in this 70s sci-fi cyberpunky style.

So I was like, Do you want to use this? And Luka loved it. So I gave him thousands upon thousands of Midjourney outputs, and he went to town on it with his awesome code. He and the people at Glitch Forge somehow made this amazing thing where you can click a button and all of a sudden, this AI image is dithered and glitchy and just awesome looking. So it's been super inspiring and fascinating and I'm just really excited to roll this out and let more people see it because I think it's really awesome.

Brady Walker: Luka. I'm curious how you got involved with GlitchForge and and glitch art in general. Looking at your website, your work as an architect and designer seems deeply intricate and geometrical and clean — it doesn’t call to mind glitch. Not to say that anybody should live in one given style, but it doesn't seem from an outsider point of view to be an intuitive jump from the kinds of architecture and design projects that you do to GlitchForge.

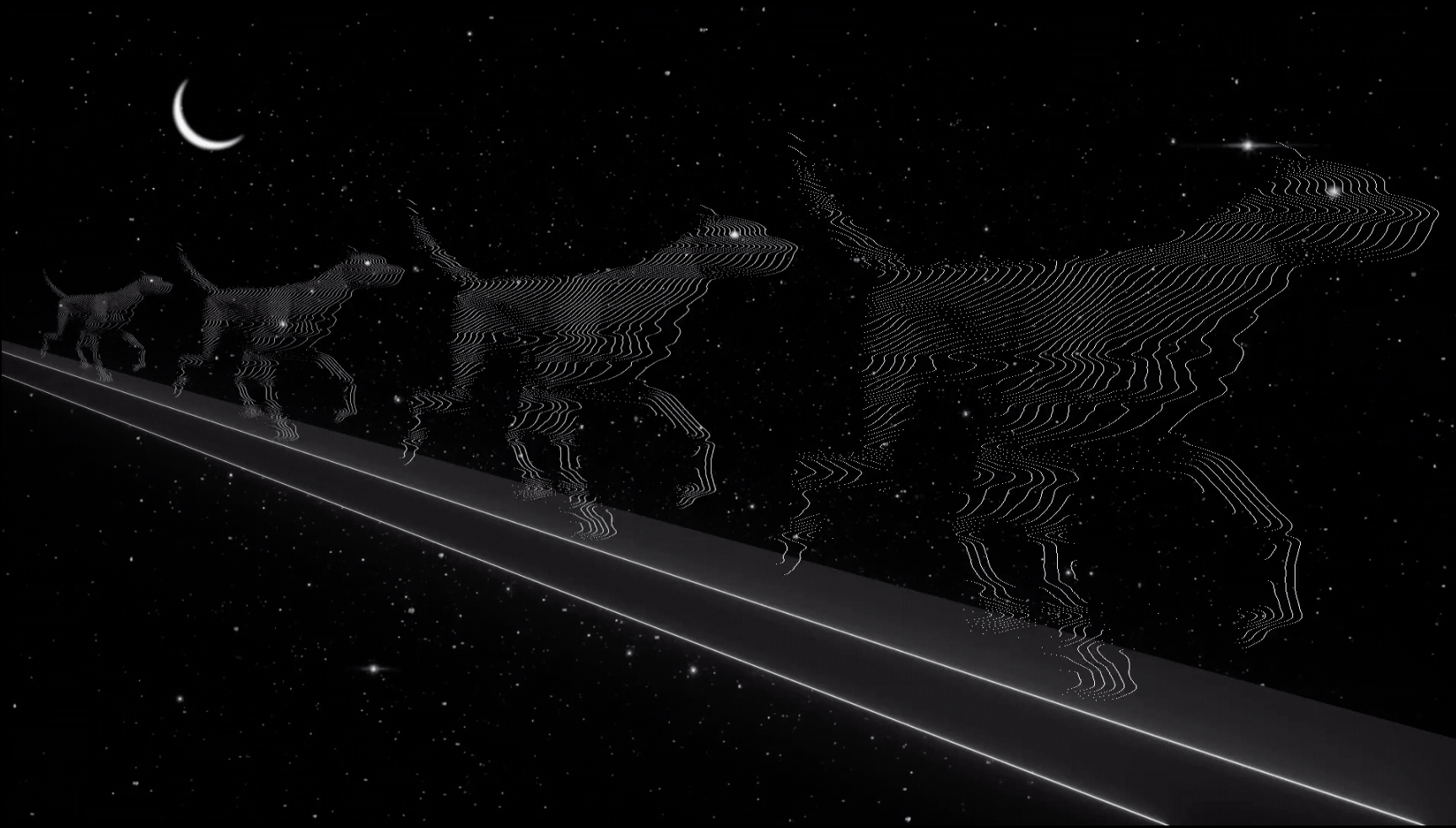

Luka Piškorec: Yeah, true. I came to it in a roundabout way. I was always drawn to retro digital aesthetics. That attracted me. I was strongly pushing Glitchverse towards a kind of retro pixel aesthetic.

I'm also a big fan of pixel art, but I cannot really do pixel art — pixel by pixel art. I can’t do that. So, I just collect work like that. And yeah, the best way that I could describe my interest in glitch art is maybe the closest it comes to pixel art, with dithering as a graphical technique. If you think about it, architects don't really work with graphics. For architects, graphics is considered to be a superficial thing. It's a representation you can use to convey your designs, but this representation has nothing to do with design’s materiality or spatiality. It's even a little bit frowned upon if you deal too much with graphics and you're an architect. I always hated that, though I'm also not really a typical architect even though I founded an office that also does standard architecture stuff — well, it's maybe not that standard, but we do build stuff.

I was fascinated a little bit with the work of A.L. Crego. He does a lot of dither pieces, and I kind of drew a lot from him. He's not a glitch artist, but I subscribe to his philosophy — this idea that we are now working on a computer, and as an artist your starting element is not a point anymore, like in art, but it's a pixel, which is like a square, a basic discrete unit of representation.

And for me, dithering is the technique where you take the simplest of elements in graphics, which is a pixel, and you create complexity by giving it structure. You can get more for less — more fidelity with fewer colors. You can take the simplest color palette, like black and white — one bit of information, and you dither it, and this way you can get all the shades of gray.

It's somehow like structural color in biology. The material itself does not really have that color; it’s the way the light reflects off the microstructure of the material that gives it the color through light interference patterns. This is a topic in biology, and it's in some sense also topic in architecture.

Because if you think about what architecture is, take small basic elements — bricks, whatever — and you put them together to get larger structures. You build complexity by using the simplest of elements. Louis Khan, the famous Estonian-born American architect said: If I take a brick and put it on the ground, I have a brick, but if I put two bricks on top of each other, I suddenly get architecture. It's a bit far-fetched, but you know, for me, that’s kind of how I think about pixels and graphics.

With dithering, you can use black and white pixels, but when you start putting them together in a certain pattern, you can get shades of gray. And with three bits of information, you can get basically what we did in Glitchverse. There’s only three bits, eight basic colors: black, white, red, green, blue, cyan, magenta and yellow. Everything is constructed from that. In a way, that's maybe the second-smallest color palette you can have in computer graphics where colors are allowed to be combined.

This feeds into this gen art idea that everything is computation, even everything visual is computation. I have a deep belief in that kind of description — that you can describe the whole world through mathematics and computation. That's basically what coding is. Computers only understand math. If you know math, and if you know how to describe the world through math, you can actually simulate the world on a computer but also create art and basically almost anything else.

Once you have this realization, then everything derives from that. I think this is also quite a radical idea because some decades ago, there were artists who would say that art has nothing to do with computers because you can't create art with computers. Of course, we cannot subscribe to that, otherwise we would not be in this field. Art has the unique ability to go beyond any definition we impose on it.

That kind of thinking also changed quite radically in the last decades, separate from the blockchain. But generative art has been there already for quite a while. Now, certain things have come together, like gen art and blockchain. As Jarid said, the fact that you can have this text-to-image generators is like operative dreaming, as you can use language to create images directly. When this technology appeared, the artist community fell into a crisis. The question was, “What do we do now?”

I think that's why I liked collaborating with Jarid. I love what Jarid is doing with — I don't even know how to call it, imaginations? Setting building basically. The standard mode was always, if you want to create a image, you need to spend a week working on it. If you want to create a graphic novel, you need to spend, I don't know, a few months on it. If you want to create a blockbuster animated feature film, you need a team of people and a year or longer.

Now you can use this technology to compress that time and effort. So maybe now you can actually create a graphic novel in a weekend. You don’t have to be like Moebius who draws for months. Does that cheapen your work? Not really. It just increases the output that one artist can do. You don't have to be a crazy guy who's working for months without pay and your wife leaves you, your kids hate you, et cetera. Now, it's a viable means of creation. So now, we'll see way more things than before. I see this as a positive development.

One last point, I think the human capacity to consume imagination is almost insatiable. In terms of fiction, we can absorb so much. It's storytelling, watching movies, reading, gossip, all these things. We can just consume it endlessly. In Japan, some people consume one manga comic per day or whatever, few of them per day, and then they throw them out. We binge-watch Netflix, a couple of shows per night maybe, and so on and so on.

Now we have this AI tool that enables us to create more and faster and somehow that's a bad thing. I don't think so. I mean, it will make us more prolific for sure. And then we can actually see the visions of singular artists in those mediums where you couldn’t create things alone. You don't need a studio anymore to create big. So yeah, I think it's positive development, although certainly disruptive for some creative disciplines.

Brady Walker: Jarid, I’m curious about how you go about trying to create something unique within with something that allows you to ostensibly create endlessly unique things but, you know — we've already all seen enough AI art, to the point that I feel like pretty often I can spot that it's AI before anybody tells me. Can you speak to your developing interests and perhaps unique style with this tool?

Jarid Scott: Yeah, for sure. Being someone who's labeled as a glitch artist, I think glitch art has a rich history in — I want to use the word like thievery, but most of our techniques and our source materials are borrowed. Someone learns a new glitch technique, then a bunch of people flood to it, try to use it and make it their own.

To have a glitch artist who produces their own base imagery is pretty rare. It’s usually someone who's either using stock photos or even just blatantly taking something that has a copyright on it. You can go down rabbit holes of remix culture and ownership and appropriation and reusing and revitalizing, but it kind of goes hand in hand with glitch art.

I already hinted that like the thing that I'm most famous for is using Kim Asendorf's code. So it's already something that someone else made. I'm not trying to toot my own horn, I'll just quote sgt_slaughtermelon. He said that I stick out as a pixel sorter because I use it in a very painterly way. I'm not saying that no one else does it. But I've done it enough — and I think if you use any of these tools enough, you can start to learn how to put your own spin on it. I see AI art as the next logical stepping stone here.

So, you know, starting out as an artist trying to stand out in the endless sea of noise of other artists. Most of my fellow glitches were using stock sites like Unsplash and Pixel Bay and Pexels. So we're all using the same stock imagery. With AI I'm not limited to what some kind person uploaded on a stock site. I can literally make anything I can think of, as long as I can put it into language, and then the AI can spit out something. And then that's literally just my basis of how I'm gonna mold it.

I understand the arguments and conversations and back and forth about is AI art real art. And what does this mean for the future of artists? But — and maybe this is a weird thing to compare to — but when television first came out, everyone thought it was gonna be the death of radio. Radio still exists today.

I simply think that digital artists have a new tool on their arsenal belt to make art from. Now, especially in the NFT space, you're seeing a lot of like raw outputs minted straight to Tezos or Ethereum. But people are getting an eye for it. It’s getting to the point where, if someone mint’s something straight, it’s like, Oh, that’s DALL-E mint, that’s a Midjourney mint, that’s Stable Diffusion.

And I think people are gonna get bored. The hype's gonna die down, and the few people who continue to hack away are going to be the ones who use it as a stepping stone to the final output that they want. I think Glitchverse, what we're doing with GlitchForge, is a great way to use AI imagery as a basis and an interesting way — to Luka’s point — to make the timeframe so much shorter. Now, like, if him, and I had tried to collab and AI hadn't been involved. I can't even tell you how many months it would have take me to make that many base images for to create our collaboration.

This infinitely expedited the process and allowed us to spend more time — well not I say us, but Luka and the developer had more time to refine the code, making it perfect, getting really nice quick outputs with interesting looking results, and that wouldn't have been possible — at least not on the timescale that we had — if AI imagery hadn't been involved.

We're just going to keep seeing more and more people develop a unique look with AI imagery and using it as a basis to start somewhere, whether it's to be just a reference sketch. A lot of people using it as the basis for glitch art, which is a great thing and it's gonna do wonders for people who love post.

The other thing that I'm excited about is what new types of art are we gonna see born from this? I think there's this giant pool of just potential creativity, and there's gonna be new versions of post-processing and editing apply to it, stuff that we haven't seen yet. So while a lot of people are running around panicking because they think it's the death of the artist. I'm seeing just tons of untapped potential. And we're just gonna see cool things that we didn't get to see before, so I'm nothing but excited about the future of AI art being married with creatives.

Luka Piškorec: Can I add a few things there? I fully agree with you, Jarid.

Few other examples. You know, when collage art became a thing at the beginning of the 20th century, when photography became cheap enough that anybody could snap a photo and then cut it out, there was a lot of “well, that’s not real art” talk. And then there was pop art. You can create prints, cheap prints, and start collaging them into your pieces. That's what Warhol did. His studio was called The Factory, like the Art Blocks Factory.

You know, thousands and thousands of prints, very cheap – Warhol produced in total 19,000 prints throughout his career. The art establishment was shocked, because first you’re reappropriating other people's work and then you're reproducing that on a massive scale. It was seen as the art of commercialization. But Warhol was basically redefining what art is, and today you have something very similar to this collage technique, but in an even more operational way with all these AI engines.

Of course, the AI models learn from all the imagery that is fed into them. Most often, simply all the images that are available online. And then you create this latent space and during generation you’re just basically exploring the latent space of these images

In a way it’s a very high-level type of collage. This is also controversial because you can restrict yourself to a certain part of that subspace, and you can create images in a style of another artist. That’s controversial because you're sort of stealing the style, but that's just on a high-level what Andy Warhol was doing in the 60s and 70s.

And again, in the 19th century the radical technology was photography. The problem with photography was that now suddenly every dimwit can snap a photo, so what about all these artists who made money by painting portraits?

This created a crisis, but from that, the Impressionist movement was born. They redefined what artists should be doing. I think this is what our space needs right now as well, time to mature. And it’s not about displacement, as nothing really dies out when it comes to culture. You know, we still have classical alongside modern music. We still have painting and photography and radio (plus podcasts!) That's just a little bit of the context that I think needs to be addressed as well.

As Jarid said, it's about pushing it to the next level. Where is that? And how does it look like? Who knows? People will push it further and new things will also come along in the future. The cycle of reinvention is unending.