“It was much pleasanter at home,” thought poor Alice, “when one wasn’t always growing larger and smaller, and being ordered about by mice and rabbits. I almost wish I hadn’t gone down this rabbit-hole — and yet — and yet — it’s rather curious, you know, this sort of life!” — Alice in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

In the language of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the story of technological innovation can be summed up as follows — every once in a while, someone’s rabbit hole becomes reality. Two questions are then important to plant the seeds for future innovation: one, what inspires the younger generation to fall down technological rabbit holes, and two, what influences their acceptance by the general public.

In answer to the first question, quite a few of today’s innovators credit the stories they consumed as children with having had a big impact on the direction of their work. For example, in 2018, Elon Musk tweeted that “Foundation Series & Zeroth Law are fundamental to creation of SpaceX”, referring to the Foundation series by Isaac Asimov and Asimov’s Zeroth Law of robotics. Another science fiction classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, inspired Stephen Wolfram to write: “It [2001] presented a vision of what might be possible — and an idea of how different the future might be. It helped me set the course of my life to try to define in whatever ways I can what the future will be. And not just waiting for aliens to deliver monoliths, but trying to build some “alien artifacts” myself.” 2001 was influential in small and big ways for staff at Apple too — the iPod got its name from the line “Open the pod bay door, Hal!”, and Hal 9000 captivated the audience at the 1999 Super Bowl when it became the main character in an Apple Macintosh halftime ad (easily one of the coolest ads of all time, isn’t it, Dave?).

These are just a handful of examples; the full list would go on and on and on. And so, given the well-documented positive impact stories have had on technologists and innovators, one has to wonder — what is the current narrative landscape, and is it fertile enough to plant seeds in the imaginations of the kids of today and the inventors of tomorrow?

Dystopias Everywhere All at Once

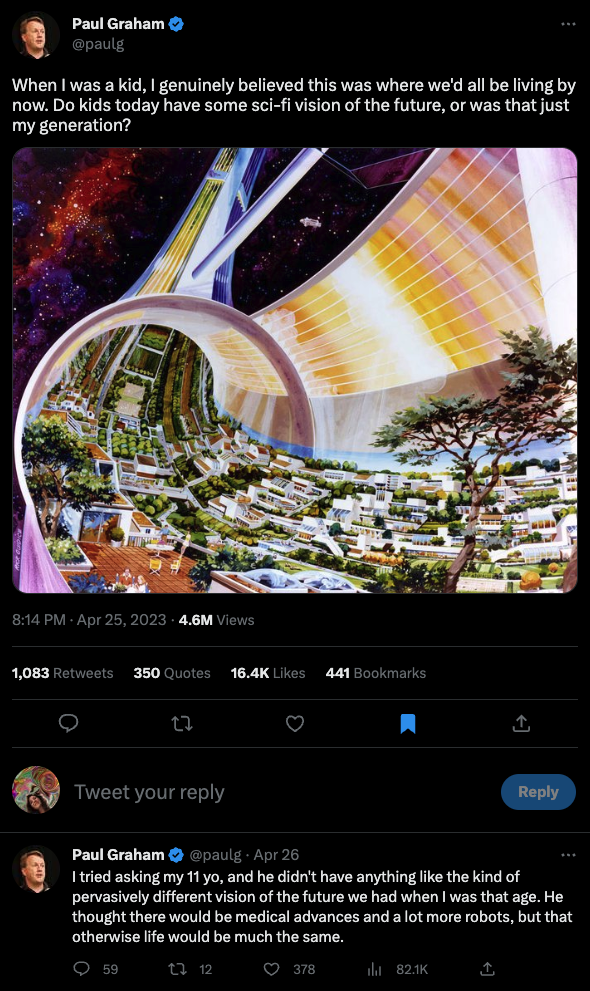

With the occasional (but notable) exception, the answer to the questions above seems to be that — compared to the past — bold, exciting, inspiring visions for the future are not as common, a sentiment that this tweet by Paul Graham captures well:

Worse, quite a few of the replies to Paul Graham’s tweet point to a future outlook that is predominantly dark, bleak, and dystopian:

Given this state of play, if you’re an optimist and a techno-optimist more specifically — i.e. you believe that technology is a key reason why we should be excited about the future — you’d be right to wonder: “When did the future switch from being a promise to being a threat?”. But as I do so, it’s only fair to acknowledge that dystopian narratives serve a purpose.

The Good

One important function of dystopian narratives is that they allow us to live out our fears about the future in a safe, fictional setting. In a world of new, powerful technologies that increasingly dominate our lives and that we don’t perfectly understand (like AI), or the consequences of which we can’t fully predict (like genetic engineering, AI), dystopias are a canvas on which we let our fears play out, so that we can better think and feel through them.

In this sense, dystopias are important in the same way that scary fairy tales are important for children. As Neil Gaiman says on the matter:

“I think if you are protected from dark things then you have no protection of, knowledge of, or understanding of dark things when they show up. (…) And for me, the thing that is so big and so important about the darkness is [that] it’s like in an inoculation … You are giving somebody darkness in a form that is not overwhelming — it’s understandable, they can envelop it, they can take it into themselves, they can cope with it.”

Through world building, aesthetics, and recognizable characters, dystopias also provide a common language in which to talk about our fears. When, for example, we worry about censorship, totalitarian regimes, thought control, we reference Nineteen Eighty-Four. When excessive consumerism, social engineering, artificial wombs are top of mind, we summon the imagery and ideas of Brave New World. After ChatGPT came out and fears of an all-powerful, adversarial, paperclip-maximizing AI that will destroy humanity became tangible, my first instinct was to rewatch Ex Machina, in which Ava, a humanoid AI trained on data from a search engine, learns to manipulate humans and ends up killing her creators.

Ideally, another way dystopias can be useful is as scenario generators for the future. If we’re then smart enough to trace back undesirable hypothetical futures to actions in the present, we can use dystopias to inform the choices we make today and avert potential catastrophes.

The Bad

Where the prevalence of dystopias becomes troubling is that while some dystopian stories offer a glimmer of hope or a small victory, they often end in demise, chaos, and destruction. The protagonist often fails to overcome a hypothetical oppressive system and instead of thinking, building, creating their way out, they submit to the darkness.

In other words, it’s not the darkness of dystopias per se that is the problem; the problem is the hopelessness, the sense that there’s no way out of the darkness that they convey. To continue with Neil Gaiman's take on scary literature for children:

“I think it is really important to show dark things to kids — and, in the showing, to also show that dark things can be beaten, that you have power. Tell them you can fight back, tell them you can win. Because you can — but you have to know that. (…) And, it’s okay, it’s safe to tell you that story — as long as you tell them that you can be smart, and you can be brave, and you can be tricky, and you can be plucky, and you can keep going.” And more: “In order for stories to work — for kids and for adults — they should scare. And you should triumph.”

It is this last sentence — “And you should triumph.” — that is key if we want to preserve the human soul and inspire. And it is also where dystopias fall significantly short.

Given the above, another way to ask why dystopias are so popular is to ask why it has become so acceptable to tell stories in which humanity doesn’t triumph. After all, dystopian narratives, like all narratives, don’t exist in a cultural vacuum. They’re embedded in and spring out of a certain cultural reality and of the values that we as a society hold dear. Perhaps it’s the very nature of our cultural reality that is driving the high popularity of dystopian visions for the future, and in the end, maybe it’s us, hi, we’re the problem. As screenwriter and story analyst Robert McKee says:

“Values, the positive/negative charges of life, are at the soul of our art [screenwriting]. The writer shapes story around a perception of what’s worth living for, what’s worth dying for, what’s foolish to pursue, the meaning of justice, truth — the essential values. In decades past, writer and society more or less agreed on these questions, but more and more ours has become an age of moral and ethical cynicism, relativism, and subjectivism — a great confusion of values.”

As a society, compared to past generations, we’re dealing with a collapse in once-defining values, a collapse in trust — in institutions and in each other, and we've traded dignity culture for victimhood culture. The following paragraphs from David Brooks’s essay America Is Having a Moral Convulsion offer a good summary of the new cultural reality that we find ourselves in:

“The Baby Boomers grew up in the 1950s and ’60s, an era of family stability, widespread prosperity, and cultural cohesion. The mindset they embraced in the late ’60s and have embodied ever since was all about rebelling against authority, unshackling from institutions, and celebrating freedom, individualism, and liberation.

The emerging generations today enjoy none of that sense of security. They grew up in a world in which institutions failed, financial systems collapsed, and families were fragile. Children can now expect to have a lower quality of life than their parents, the pandemic rages, climate change looms, and social media is vicious. Their worldview is predicated on threat, not safety. Thus the values of the Millennial and Gen Z generations that will dominate in the years ahead are the opposite of Boomer values: not liberation, but security; not freedom, but equality; not individualism, but the safety of the collective; not sink-or-swim meritocracy, but promotion on the basis of social justice. Once a generation forms its general viewpoint during its young adulthood, it generally tends to carry that mentality with it to the grave 60 years later. A new culture is dawning. The Age of Precarity is here.”

When the general sentiment is that the future is precarious at best and in all likelihood worse than the present, the grand visions of techno-optimists — even when grounded in real, tangible progress — sound out-of-place and almost insensitive.

This is why, if we want more optimism, the most strategic solutions are: one, a new era of prosperity, or two, a cultural reset. With the help of AI, a new era of prosperity might be just around the corner. A cultural reset on the other hand will require concerted multi-party efforts to re-build trust and improve social health, and is likely to take some time. Strategic solutions of this scale are however not in the scope of this essay. What we’ll look into instead are possible techno-optimistic narrative solutions.

And the Possible: an Incomplete List of Narrative Solutions

One category of ideas concerns what tech companies themselves can do. For example, we could use more well-advertised, dramatically staged, and well-explained product releases, much in the tradition of the iconic Apple releases. Most recently, SpaceX’s Starship and Falcon launches have been blurring the lines between science fiction and reality, and have given kids and adults alike tangible reasons to be excited about the future:

Inspiring products and product launches also tend to have direct, immediate effects on the interests and even career decisions of children, as this story about a young Apple II fan in the 1980s and the picture below demonstrate.

Yet another way for the tech industry to directly promote techno-optimistic narratives is through more numerous collaborations with science fiction writers. For example, a few years ago, Microsoft had a project called Future Visions, for which the company invited writers to their research facilities and gave them access to top scientists. The result was a published collection of original stories inspired by Microsoft’s work in various (then cutting-edge) fields such as prediction science, machine learning, and quantum computing.

Moving away from the tech industry, one tactical way to enrich the narrative diet of the next generation is to tap inspiring sci-fi classics and re-interpret them for our day and age. The 2021 TV series Foundation, loosely based on Asimov’s work, and the 2021 Dune movie directed by Denis Villeneuve are great examples of powerful new adaptations that leverage modern cinematic capabilities.

When AI-generated video improves further, yet another barrier to more abundant techno-optimistic narrative production will fall as it won’t be as expensive or time-consuming to make stunning science fiction movies, be it adaptations of old work or new, original stories. In addition to traditional formats like film, these can be distributed in the mediums that the younger generation prefers, such as YouTube or video games.

The ideas outlined above mostly cater to an audience that is already somewhat interested in or open to technology. But what are we to do — from a narrative point of view — if we want to overcome the hesitation of outright techno-skeptics?

One solution is what I like to call diplomatic futurism. Diplomatic futurism is essentially product placement where the product is techno-optimism. The premise is simple — it’s possible to convey a techno-optimistic attitude by avoiding an explicit focus on technology. The point is to show technology in a non-intrusive, non-intimidating way by presenting it as a non-controversial fact of life (the way iPhones are shown in movies now, for example).

What does this look like exactly? Take the trifecta of technologies that are currently the subject of public skepticism — AI, crypto, and nuclear:

Diplomatic AI futurism might look like this: in one scene in the movie, we’re in a small village in India when the protagonist’s AI-enabled wearable sounds an alarm as it registers a sudden deviation from the baseline. The wearable recommends an urgent and complex surgical intervention, so the protagonist is rushed to the local clinic. Even though there is only one non-specialist doctor, with the help of an AI-assisted robot, he is able to perform a successful surgery and deliver the kind of top-notch healthcare that in the past only large, specialized hospitals could provide (yay!).

Diplomatic crypto futurism might look like this: the protagonist is traveling with her friends in Argentina. They’re about to check into a small hotel outside of Buenos Aires. They’re told they can’t pay in pesos because inflation is too high and the local currency is not a good store of value. Since it’s Saturday night and banks are closed, a withdrawal in another currency is not possible. The protagonist ends up asking for the hotel’s Bitcoin address and pays for her stay with her crypto wallet (yay!).

Diplomatic nuclear futurism might look like this: the young protagonist visits his Dad’s workplace as part of Take Your Child to Work Day. His Dad works at the local nuclear power plant. The children are shown around the sparkling white, beautiful facilities, and during the walk, the protagonist’s Dad explains to them in an easy-to-follow, friendly way how nuclear energy works. And that’s it, the nuclear plant is just this — the place where the protagonist’s Dad goes to work (yay!).

In all of the above examples, the exposure to the tech is somewhat of an aside. But repeated often enough, asides create familiarity, and familiarity can change attitudes. Much like in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, where Elliott is initially scared by the alien creature but eventually forms a friendship with him, through repeat exposure, even techno-skeptics can get used to the otherness of technology and learn to appreciate its capabilities. For such is the power of narrative solutions — good stories well told spark curiosity, and curiosity can help us guide the skeptics to some form of techno-optimism and the next generation towards new and fascinating rabbit holes. There is, of course, no guarantee of success, but hard try we must — this is the way.

~ end