ANONYMOUS IN CONVERSATION WITH TRAVIS WYCHE

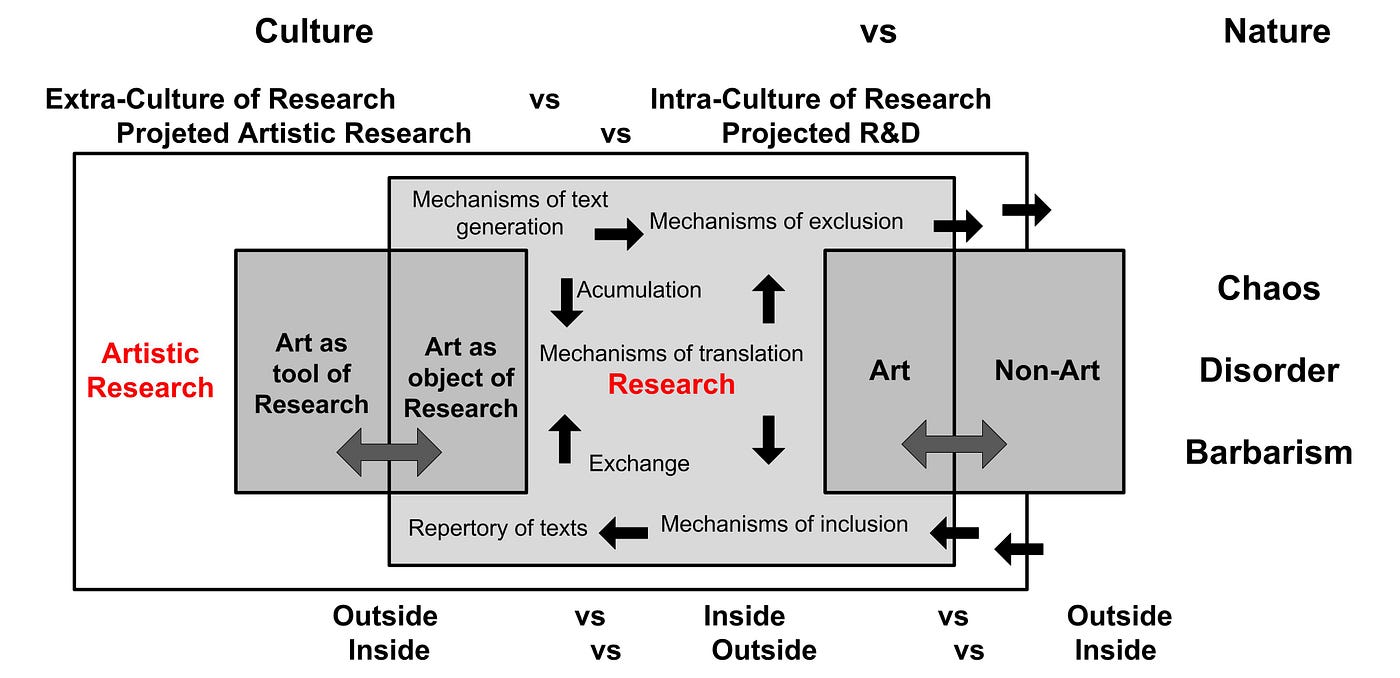

We could begin with the question that I wrote down for our conversation last week, which is why research? Why call it research? Where does that come from? Tell me about that decision. Is that yours? Or is that slotting of the work into a category already created by the granting body, MolochDAO? I think the question of why research connects to questions of genre and style.

I don’t know if I understand the open-endedness of the question. Why research, as opposed to another word that might carry a different set of cultural connotations or imply another level of rigor or causality or casualness? Why call it research and not a conversation?

Why research as opposed to a story? They are so many things you can call written narratives. Why research? Is that about importing an idea of seriousness? Research typically implies a method, so are there presumptions about method? Why research is also another way of asking what is the method?

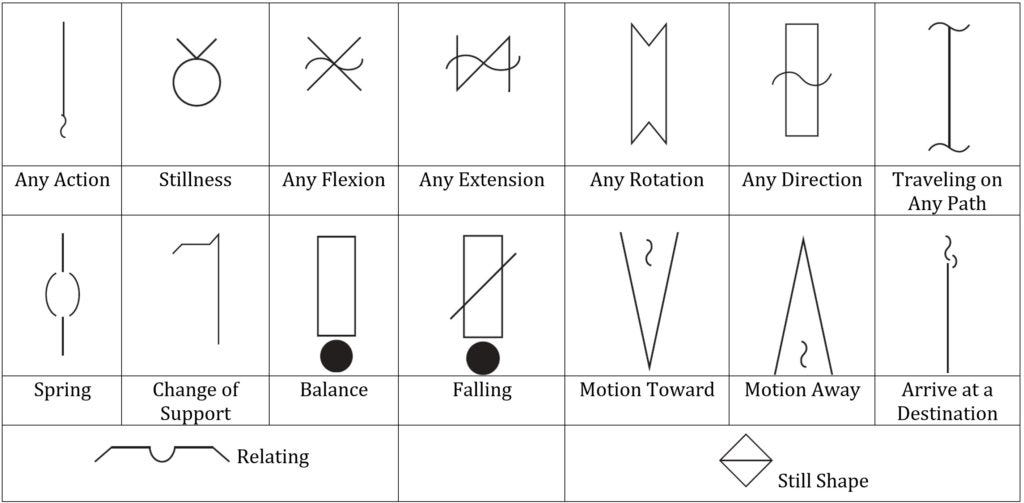

Research is a term that carries with it an implication that what is being offered has been attended to with a certain kind of care and depth. I have a lot of qualms with this word. I throw it into the bucket with other repetitious and iterative concepts. It implies a return to an earlier search and in my experience as an artist I’ve always been more preoccupied with the importance of initiating novel forms of searching, emphasizing the search as a method in and of itself rather than reiterating archived searches from history, revisiting other conceptual artifacts of knowledge and applying them towards a contemporary condition or local problem. I think traditional research lacks a sense of immediacy and creative discovery. It is fundamentally innovative, but it is not creative, by which I mean it takes stuff that already exists and iterates on top of it, dismantles it and puts it back together.

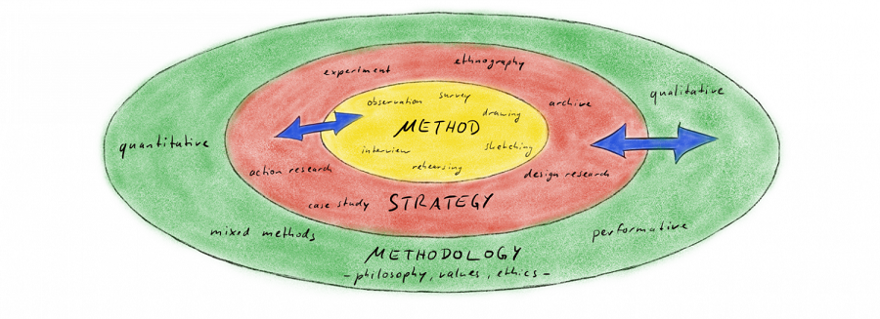

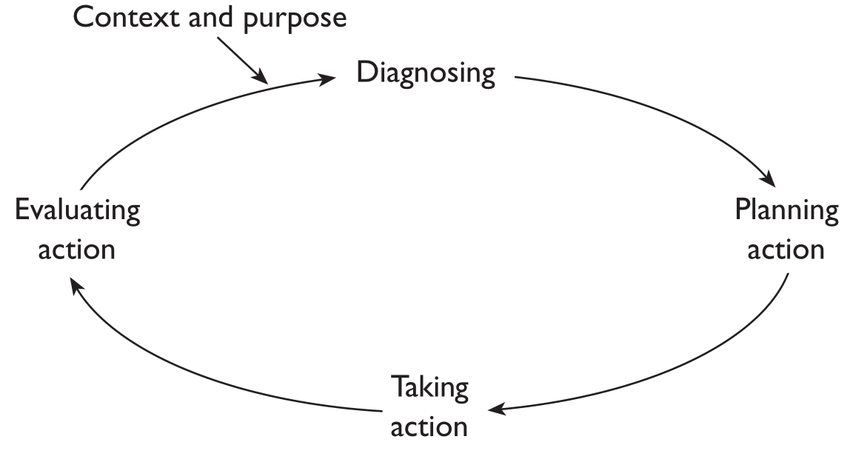

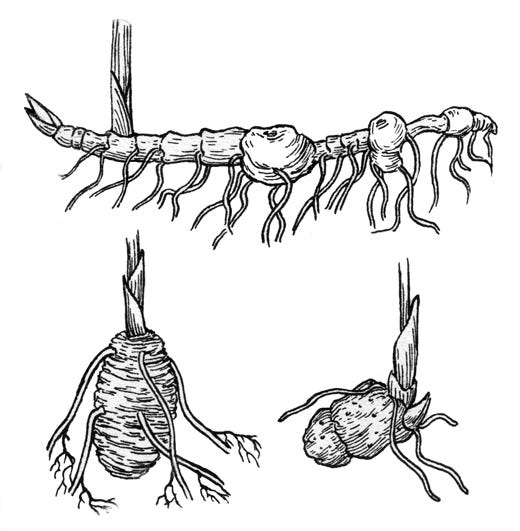

I’m very interested in applying a different kind of method, of discovery and creation, that intends to generate something from nothing. When I say research I mean something much more akin to searching, or as you mentioned earlier pre-searching, which we might consider as an excavation into the foundation rather than building something on the surface, or molecularly probing the constituent parts in a mechanistic way to understand the material essences of the thing. This series of conversations under the awning of DeathGuild is a response to a lack that I have felt within the Web3 community, to dive deep into the ontological and epistemic foundations that the concepts within that community are built upon.

There’s two parts to your asking-after our method. One is in the understanding that I’m not interested in orchestrating or curating a method that would incorporate a rigorous empirical system, a scientific method, although in terms of the mechanics of logic we can hardly purport to escape that sphere of influence. What I just described is a hypothesis to be conducted through specific procedures in order to generate certain results that might be scrutinized for their efficacy afterwards. To that extent, we are appropriating empirical methodology. The oppositional method I hope to put forth begins with an impulse to allow the tensions within the conversation to lead us towards unpredictable, unexpected, surprising areas, which must not be presented as conclusions. I hope that the end remains as open as the beginning — or more so — and that the entire conduit is maintained as a vision of porosity that remains diffuse, or rhizomatic perhaps. I hope that we maintain a subterranean demeanor, stay dirty without ever trying to clean ourselves off.

Something that I want to say about that specifically, about the commitment to porosity and mess that you’re describing, is that it feels important to point out that it can still involve a lot of precision. I’m thinking about these DAO manifestos that you shared with me. In my reading of them, they don’t really say anything. It’s just a lot of cliches and stock phrases and really huge concepts with words that are strung together. One can think about that as a certain instantiation of porosity or mess. I feel like it’s really important to distinguish the kinds of processes you’re describing from that relationship to language, where there really is no control over terms in a way that feels like a word soup of industry lingo. I wonder if that idea of precision speaks to you somehow, because I think that one thing that can be difficult with creative research practices that are intentionally non-empirical or scientific is that they can be critiqued for not being precise. I think it’s really important to showcase the ways that artistic practices, literary practices, and non-scientific practices are precise in their own ways. There is also a way of piggybacking onto scientific lingo where there’s no rigor.

I’ve found myself having a similar reaction, a cynical and critical reaction, to the DAO manifestos or any document that presents and broadcasts an ideology intended to align a community around a tech product or an agenda. I do find it wonderfully porous and yet dishearteningly lacking in acuity, which is what this project attempts to respond to. Let’s discuss your use of the word precision. I have a bit of an antagonistic relationship with precision as it implies the honed metric, like a dissecting scalpel, a quality of an instrument for empirical dissection.

In my dissertation I’m trying to build a case for precision that carries a different set of connotations. When I say precision, I don’t mean to say that there is value in a high-fidelity, realistic photograph that is lacking in an abstract painting or in some other kind of representation that is inexact. There could be a painting that captures a mood perfectly that is not a high-fidelity representation of a place or space or event. I’m trying to define precision as something that is apt in the way that an absurd joke can be a precise reading of a social situation even if it is not logical, as opposed to a precision that is about measurement or exactitude. Scientific cultures have a monopoly on the idea of precision, even though there are lots of other forms of precision.

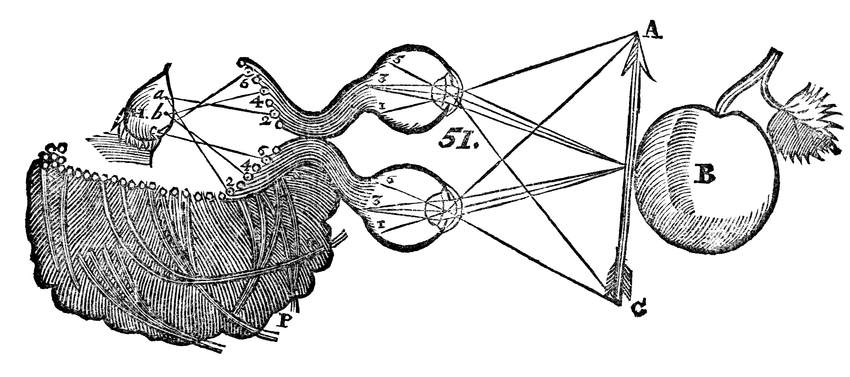

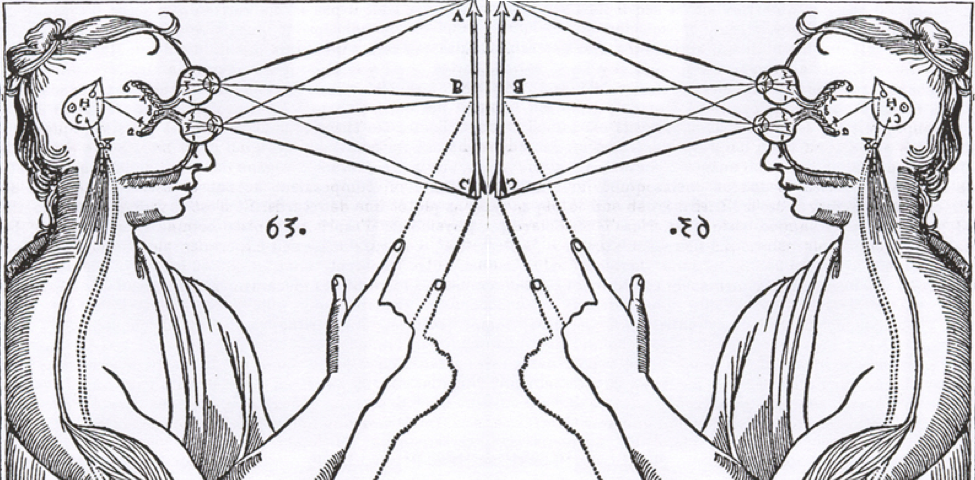

A juxtaposition of accuracy to acuity belies an orientation to critiquing and to analyzing an object under scrutiny as the empirical drive. Acuity implies an optical bias; the acuity of a lens, the acuity of an eye. Accuracy is rooted within a mechanism of reason, a logical apparatus applied to physical apparatus. You bring up representation indicating the primacy of the thing being re-presented, of the thing that is presented again, and the metaphysics of that optico-centric bias is at the root of both interpretations. This is not a cause to dismiss them as somehow tyrannical, negative, pejorative, or otherwise lacking in utility for having a conversation about what is presented and how it was represented in artifacts of culture, but it makes me wary in how I wield these ideas as conceptual tools just as I would be wary while manipulating a scalpel with the intention of slicing something open, aware that I could also slice myself. I would love to go down this path of how you are developing or maybe re-developing the concept of precision. With re-development we get sucked into the infinite regression of re- re- re-developing and re-developing and re-developing, ad infinitum, ad absurdum. This is the empirical history that we might consider wielding more delicately so as not to be cut by it here at the outset of this project.

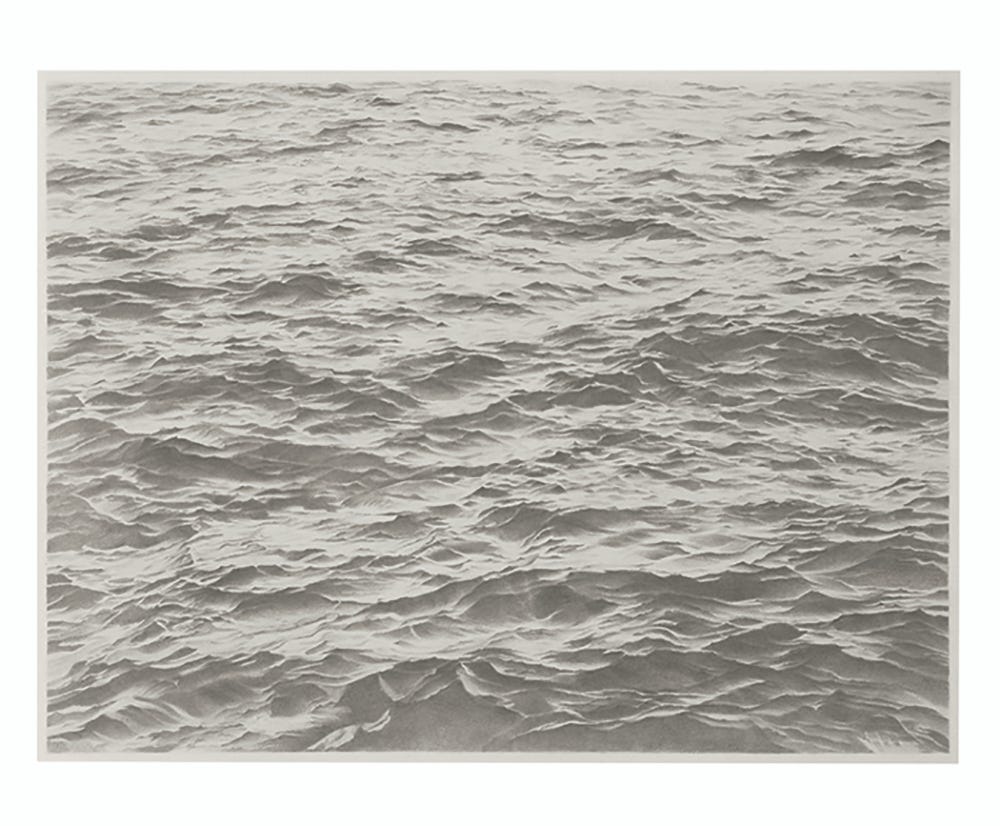

I would say a meditation on acuity and precision aspires towards definition. Definition is a tripartite concept; to render definition involves resolution, fidelity, and latency. Bear with me. With the painting that you mentioned earlier, where you are attempting to decipher its accuracy as precision in its representation to the thing depicted, rendered as an image, I would say that the resolution of that painting would be the technique, the mannerism of the manipulation of the material substrate of the painting. It would be revealed through the choices of the material languages: whether it’s painted on canvas or linen, whether it’s framed or unframed, the choice of brushes and of paints, and the quality of those materials, as well as in the skill of the artist in being able to manipulate them to a specific end. This would constitute the resolution, which might be high or low, but that doesn’t necessarily render the image at a higher or lower definition.

The fidelity of the image would be a separate consideration. To shift the metaphor a little bit away from a painting into another kind of framed image on a screen, if the resolution on the screen is the number of pixels that illuminate to display the image, then the fidelity would be the information contained within the digital file being rendered. In terms of painting, resolution would be the manipulation of the material substrate, whereas fidelity would be the image of the world being presented. The re-presented world may be a high-fidelity representation, which goes to great extremes in genres like photo realism, or a very low-fidelity representation, which reaches great extremes through the whole 20th century performative play with abstraction.

Latency is the third pole of this triangle of definition. The speed that we were able to become aware of the manipulation of the materials and of the intention of the image being depicted contributes to our ability to render it accurately, to exercise an acuity of the precision of the image. If the image that is being stylized is opaque and calls attention to itself more than the thing being presented, we might say that this slows down the viewing experience or maybe even creates a surface that our eyes skim over or are deflected off of, are repelled by perhaps, so that we cannot see the image directly. While an image that is rendered at a very high-resolution and a very high-fidelity may appear crystal clear — we can see that it is a picture of something and we recognize what the something is — the style imbibes so little latency, or we might say that the experience of the image occurs at such high-velocity, that we can scarcely begin to contemplate the style of how the thing is rendered or entertain that there might be a manipulation of the image presented. It is immediately perceived as something true to life, unquestioned.

I’m having trouble with this idea of latency. Let’s stick with the painting analogy that we’ve been working with. If a very specific object, a bowl of fruit, is painted in a way that interrupts the speedy delivery of that representation into my eyeballs and consciousness, it may nonetheless, at the same time, immediately deliver a certain mood or an experience of disorientation that is precisely the point of the painting. Guide me if I’m misunderstanding what you mean by latency, but the way that you’ve set it up feels like it privileges the represented object, where the point might be, for instance, the mood and not being able to distinguish the contours of the bowl of fruit in an ordinary way.

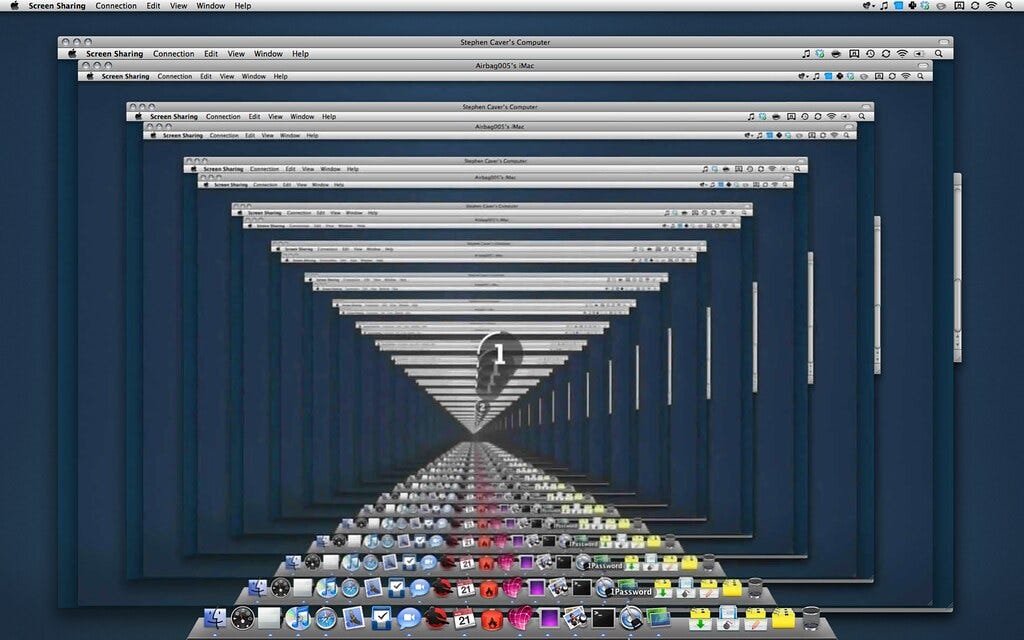

In ancient Greece, Zeuxis and Parrhasius were two painters that engaged in a contest for who could make the best painting. They evaluated their work by how* true to life* it was, how convincing the representation of reality could be. Zeuxis painted the bowl of fruit sitting on the table next to them. They analyzed it together and Parrhasius exclaimed that it was almost perfect, that he could see no difference between the painting of the fruit and the bowl that was sitting on the table. So certainly Zeuxis must have won, but first they were to inspect Parrhasius’ painting hidden behind a curtain. When Zeuxis went to lift the curtain he discovered that the curtain itself was in fact the painting. The root of this story is that conviction stems from when representation becomes obscured as immediate presentation, becomes primary experience, becomes indecipherable from the phenomenal world that contextualizes it. There’s a tradition of this in painting, like with Trompe-l’oiel: murals on walls that convincingly depict outside scenes, turning the substrate into a window that we look through without questioning the substrate, effectively dissipating the substrate through high-resolution and high-fidelity means so that we just look through the surface into a seamless, continuous world.

Might we steer this back to what we’re doing in this project and what our intentions are? I think that you had some questions about genre, style, and how we render the objective of this research to convey a certain methodology for a purpose or to make it legible?

Before we go back to that more grounded set of questions, I think it’s worth pointing out that we still have a disagreement about precision. It’s really important to object that I don’t think that precision always aspires towards definition. That is the polemic I’m developing and is also quite relevant to how we undertake whatever this work is; research, storytelling, or whatever it’s called. I would disambiguate precision from definition. I think there’s a way to be precise without being definitional. Precision is expressible in description, as opposed to definition. Description is not necessarily definitional. I like the Wittgensteinian invitation to think in terms of family resemblances, as opposed to concepts. Whereas concepts have to be sharply cut, like gems shaped in a certain way, what determines the grouping of family resemblance is the context. There isn’t a need to make something distinguishable in a context independent way. To put it in the terms of Karen Barad, there are always decisions to make about cuts and those don’t need to be carried by the word or the description itself. They can be negotiated in a community.

I would purport that there is no identification without context, otherwise the representation becomes mere presentation. Our ability to identify is facilitated by contextualizing. Identification enframes and without the framing and the framework built around the thing being observed it cannot be identified. I would say this is the ontological orientation of identification, to place frames on the world, even if it’s just within the field of vision as a frame in itself. I also think that you’ve created a bit of a false postulate in juxtaposing description with definition. Description is in itself a representation, but I would argue that although primary presentations can be evaluated by their definition, just as representations can, descriptions of descriptions leads to an infinite regress of representation, as in any media replicating itself in any other media — which is to say any description describing any other description — amounts to an infinite regress of representation. Such replication does not approach acuity or accuracy or precision, but merely modulates the definition of our ability to identify.

My offering to consider definition is focused upon how we render an image in response to your prompt for us to consider style. There’s a mannerism inherent within descriptions, just as there is a mannerism of painting styles and a mannerism to photography techniques, but the stylistic considerations of rendering the definition of concepts gets folded into the dough as we are assembling ingredients for sharing in those concepts. This is especially the case in a conversation such as this one, where we’re asking what are we doing and how are we doing it and what is the difference?

To me description and definition are incredibly different. Maybe I need to pick a more precise word, but definition is the desire to simplify phenomena, to make it fit into a category. Description is remaining faithful to the phenomena in a way that’s different from definition. Both description and definition are re-presentation, absolutely. For me, descriptive and definitional gestures are kinds of representation.

Not absolutely. Definition isn’t a representation of phenomena, but the cognition of phenomenon. Definition in this sense delineates the parameters for how we identify, for how we cognate. Description — along with any other representational medium to the extent that it remains faithful to the phenomena being presented — is representational to the extent that the more faithful it is, the more it aspires to duplicate the thing being presented. Maybe there are other factors to representation we might consider other than just its duplication or replication potential, as indicated by the history of abstraction. Definition is not an attempt to compartmentalize, to create taxonomic structures upon which to hang phenomenal specimens or captured qualia of experience. It’s an attempt to measure the intensity of that experience, which I believe is described as an inherently optical experience. The optico-centric bias that I try to remain aware of purports that all experience is rooted within a visual experience. Presentation and representation is embedded in the descriptions that we use to describe the phenomena happening around us. A beautiful, wonderful paradox, isn’t it? As long as we don’t get too entangled in it.

I think this relates to a notion you were bringing up during our last session concerning the absurdity or tragedy or paradox of attempting to devise a system that explains an element of human behavior or human experience while also being wrapped up within the very behavior or experience that we are attempting to explain. We were talking about governance as a theoretical architecture that we use to negotiate human relationships, but governance would happen even without the concept, as a de facto form of human relations. Definition and description are inextricably bound to each other. We are experiencing while attempting to impose conceptual-theoretical frameworks over what experience is and these processes cannot happen simultaneously. You cannot see a thing and also understand the thing that you’re seeing in the exact same moment. This is the importance of latency: you see it and then you see that you’re seeing something. You see it and then you begin to understand what it is you’re seeing, and then we move into the analytical realms of ruminating upon what we’re seeing and how we’re seeing it.

It was my claim that description and definition are both forms of re-presentation and it seemed like you disagreed and it seemed like your position was that definition is not a kind of re-presentation. If what is seen cannot be understood in the self-same moment, then what is understanding if not a re-presentation of an experience that could not be comprehended in continuity with its being experienced?

I think I agree with everything that you just said. Definition is a concept, a triangulation of resolution, fidelity and latency. That’s all conceptual, theoretical, a model, a mental geometry, and what it attempts to describe is the procedure of phenomenological experience. When you’re seeing something, you’re not thinking about the resolution and the fidelity and the latency, and yet those are the metrics of intense identification, of applying the framework we mentioned earlier. Description is the iteration of that experience into a communicable form, which is why it’s representational. These descriptions of representations are produced as artifacts and the accumulation and organization of those artifacts, both theoretically and physically, amounts to culture. Culture is the crucible of knowledge.

I now understand why my opposition of description and definition didn’t seem to work. I think that we’re using definition in different ways. If I’m understanding you correctly, definition as the procedure of phenomenological experience is the substrate from which descriptive gestures or practices would then be made and description is the communicable form of whatever we agree is the procedure of the experiences of definition.

I’m lingering on your use of the word substrate. What I don’t want to do is present it as a de facto, a priori, natural materiality in itself. Definition is certainly very much a form of conceptual instrumentation. I’m rooting myself within the very optico-centric bias I’m trying to see my way out of, inherited by the Cartesian mind-body-problem, Copernican mechanistic universe, of instrumentalizing our own percepts. Admitting the paradox that I’ve wrapped myself up in, I would say that this concept of definition is the variable for understanding the mechanism of the optics of our eye as it renders the world into information. Description utilizes the data that’s generated from our phenomenological experience and we can make sense of that stewing miasma of data by imposing constraints. It’s not the miasma, it’s not the substrate itself, in the self-same moment.

Let me make it like a tiny bit more messy, just for fun, and then we can stop drowning.

I’m game.

I’m looking at a book that I adore by William Gass called On Being Blue and it’s making me think about certain people that lack the word for the color blue. In the Odyssey or the* Iliad* we get the wine-dark sea; we get all of these other forms of description for the color blue. To what extent does a lack of descriptive resources change what one is capable of seeing or not seeing? The way I’m thinking about description and definition is as two really broad genres of utterance. Definition is a stand-in for concept mania, my cheeky way of thinking about philosophical and scientific culture. It belongs to a dialectic. It’s not the case that we can or should exorcize conceptual thinking and conceptual language; it’s absolutely integral to the human form of life as we know it, for now at least, and so even if it was desirable it wouldn’t be possible. Within our culture there has been an over-cultivation of definitional capacities, concept-making kinds of capacities, at the expense of something that I’m calling description. It’s an over-developed muscle for simplifying and reducing phenomena so that it fits conceptual or definitional contours, at the expense of the struggle for descriptive language that might attend more faithfully to phenomena.

How does this help you understand the DeathGuild project?

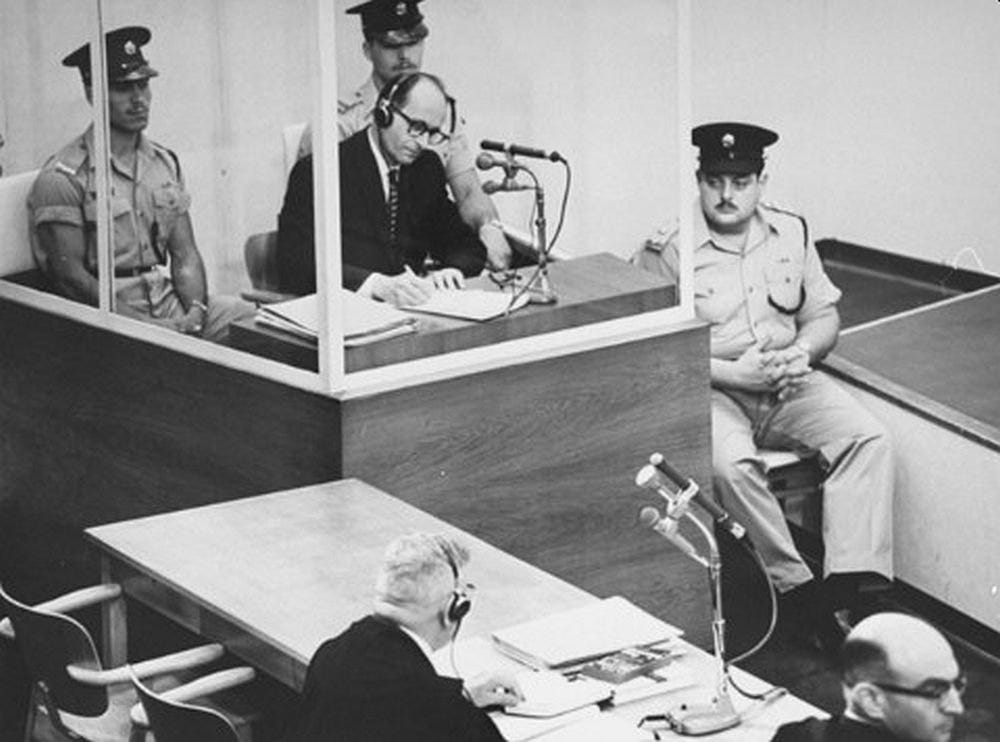

I think I have a way of getting back to that, but it will seem like a detour for a second. Are you familiar with Hannah Arendt? Have you read this text, Eichmann in Jerusalem? It’s basically a series of pieces that Arendt was commissioned to write for The New Yorker in which she covered the trial of the Nazi, Eichmann, who was kidnapped from Argentina and taken to a tribunal. The series of reports that were published in *The New Yorker *were compiled into a book. This text is a really beautiful example of the preoccupation I have with description over definition and I think is a great way of relating this problem to questions of genre.

Hannah Arendt is a trained philosopher and within philosophical culture there’s a long standing tradition of asking about evil, trying to figure out what evil is and trying to define evil or reframe the problem of evil. Arendt goes into a pretty exceptional legal context in which Eichmann is being tried in Israel and she’s pretty cynical about it. For her, it’s a show trial that has a lot more to do with establishing the State of Israel than it does with doling out something that we could consider to be justice. Part of what makes it such a captivating work for me is that Arendt enters the courtroom without any legible professional obligation. She’s not one of the judges, she’s not playing any role in the proceedings, except to witness and observe them. As an observer, or witness, she brings to the proceedings the rigorous conceptual training that she received as a philosopher. You see all these instances in the text where she has a capacity to experience the phenomenon of Eichmann being on trial without any particular institutional language. She had a command of all of the different languages that were being spoken in the courtroom; she wrote in English, she could understand the proceedings conducted in Yiddish, Eichmann spoke German, and there was a translation in French, so she was able to observe all of the ironies that were happening beneath the surface inaccessible to an observer that spoke a single language.

She was not trying to clean up Eichmann’s actions to fit her conception of what evil meant. She tried to experience the trial of Eichmann as a portal into a new understanding of what evil might be. She came up with the expression banality of evil, which caused so much rage within the population of general readers. That claim was very different from the way that evil had been defined by people in the philosophical tradition. The book reads like literature, it reads like anthropology, it reads like history, it reads like political theory; it’s all over the place and its lack of clean, generic contours relate to a commitment on the part of Arendt to be faithful to the phenomena, as opposed to stepping into that assignment to administer her concept of what evil is, or administer her concept of what justice is. To return to this question of how this relates to research and method for DeathGuild, this is maybe all a long winded affirmation of the approach that you seem to be advocating for, which is to have a bunch of experiences together that bring up whatever they bring up and not impose any kind of architecture or framework on the conversations ahead of their happening.

And also not to impose any personal biases upon the subject matter that we are ruminating upon together and to remain open to the cultural proclamations of the specific group this research project is growing out of — consisting of web3/Dapp developers and crypto-economic financiers — while recognizing the banality of the utopian idealism that is emerging from this community, as though from scratch, as though it were somehow an original idea.

I consider it impossible to avoid bias and inhabit a neutral standpoint. I think my own orientation will be to try as much as possible to recognize and openly acknowledge the places where that bias and that cynicism and that repulsion exists for me, making an effort not to be fanatical about my biases. Speaking for myself, there’s a bigger danger in repressing the bitterness, or whatever it is, and pretending that there’s a neutral place that I’m starting from. I want to be a little bit crass, because that’s the hot take that I haven’t wrapped up and put an educated bow on top of.

The crassness is important, and the risks that we take in our crassness, because yes, of course, there is no such thing as neutrality, but the claim of neutrality is so horrific. I would rather be a Dadaist in 1940s Switzerland making obscene gestures and absurd symphonies than a government official of Switzerland purporting to be somehow neutral to the World War happening at their doorstep.

Neutrality is ridiculous, because it’s another way of saying I don’t yet have any skin in the game, or this doesn’t affect me directly. It’s something that is allotted through great privilege. It is monstrous to those that have no privilege, that have no voice, that are not able to exercise the privilege of remaining neutral. To that extent, DeathGuild seeks to be fervently opposed to the obscene and flagrant wielding of the banner of neutrality. I would even go so far as to say that we should strive to be crass at the highest definition possible, an excruciatingly high-definition crassness, for sake of both the definition and the description of the perspectives that we are attempting to wield with the utmost nuance and subtlety! We should respect that this is a long journey. Even though these articles will be released in installments, I feel like we inhabit a more confused state now than at the beginning, and this might be celebrated as a crass or perverse inversion of a pragmatic agenda of arriving somewhere safe and sound, clearly articulated, so that we might all immediately forget the message and get back to work. Never work, I say! Another avant garde slogan. That’s Situationism now. Perhaps that should be the DeathGuild method.

I think people might hear a statement like that and think that it is a statement against labor. I think that it’s important to think about labor and work as distinct. Rejecting work is not a rejection of laboring.

I think this is a very good conclusion without concluding anything.

I want to say one more thing before ending. You’re talking about rejecting neutrality and it made me think of one of the DAO manifestos in which the author wrote some stuff about wanting to gather a nation, evoking this language of no borders and no passports. This is where Hannah Arendt is such a compelling thinker. Her preoccupation is with the way that the intellectual tradition thinks about The Rights of Man. When it was actually put to the test, during a time when there were hordes of stateless Jewish people, it turned out that all of this high-handed language from the Declaration of the Rights of Man was completely meaningless. It turns out that being protected by a nation, having a passport, being legible in that way, is the only way to protect the dignity of people. I’m not saying that she is 100% correct — this is a whole other conversation to have — but in terms of putting pressure on this ugly neutrality that is visible in the tech sphere and other places, I think she’s a great interlocutor to consider. Who is clamoring for no passports? How do we think about the ideal of no passports historically? How does that relate to the possibility to utter such statements made possible by the great privilege of having a passport from a certain nation? Let’s not attempt to kill the idealism — because the idealism is fucking rad (!)— but might we rescue that idealism from toothlessness?

This series is made possible by a generous grant awarded by MolochDAO. Thank you Moloch!