The Nobel prize winning economist’s take on human behaviour and rationality that helps us remove our biases and make fewer mistakes in our decisions.

Thinking fast and slow is one of those books that needs a mountain of patience and persistence to finish and completely assimilate. A book that I have taken more than a year to complete —marching steadily, one page at a time — it deeply impacted the way I think every day. Below is my summary covering the key ideas of the book. Like the book, I split my summary into 5 parts (it is impossible to cover it one post) and this is the first among the five.

Daniel Kahneman, the author of Thinking Fast and Slow, introduces the book as an attempt to provide a deeper understanding of our judgments and choices in everyday lives by enriching our vocabulary. His analogy is simple — a doctor needs to know a large set of labels for diseases — with every disease name tied to an idea of its symptoms, causes and treatments. Similarly, a richer and precise vocabulary for our thoughts will help us identify and understand errors in our decision making and judgements.

Starting with an example that hints at the theme of this book — “Steve is very shy and withdrawn, invariably helpful but with little interest in people or in the world of reality. A meek and tidy soul, he has a need for order and structure, and a passion for detail” Is Steve a librarian or farmer?

Most of us would decide that Steve is a librarian just because his description resembles one. But rarely does someone think of statistical facts (there are 20 farmers for every 1 librarian) to make an accurate guess. This reliance on intuition leads to predictable biases in our decisions and the book explores various such biases.

Two Systems

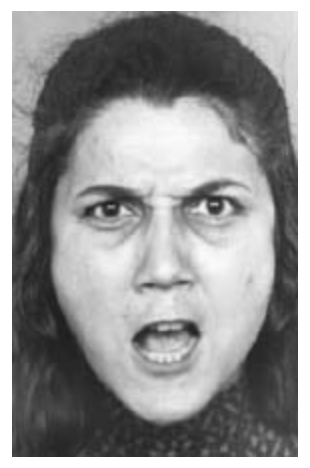

You must have already guessed the mood of the lady

As soon as you saw the picture, you did not just see the facts (physical attributes and her state of anger), you also had a sense that she is about to yell some foul and unkind words. What is interesting is — you neither made a conscious effort nor intended to evaluate any of these things. Yet, it just happened and your mind ended up drawing these inferences. This, is ‘Thinking fast’.

Not so easy

Now what is 17x24? While you knew that it is a multiplication that you can solve, and have a sense of the range the answer might be in, the answer does not pop in your head. By the time you arrive at the answer, your mind goes through a sequence of steps — retrieving the memory of how to perform a multiplication and actually implementing it. This deliberate, effortful and orderly thinking is — ‘Thinking slow’.

System 1: One that is responsible for ‘Thinking Fast’. The mental events that occur automatically and require no effort. These are mostly involuntary — our instincts, biases and all actions that we do on an autopilot mode.

System 2: One that is responsible for ‘Thinking Slow’. It requires attention and effort, and finds difficult to multitask.

Tasks that start as System 2 can turn into System 1 with practice — driving a car on highway needs a lot of concentration for someone who has just learned to drive, but for seasoned drivers, it is quite effortless and ‘just happens’ (The same can be said about the intuition and ease with which people skilled in a specific field operate — like they are in a state of flow). But when the task gets difficult — say a dangerous overtaking manoeuver on the highway — System 2 kicks in where the driver needs to put in mental effort and will rarely be able to multitask (stops talking with co-passenger till the overtake is complete). Another example is — pace of your walk slows down if you are trying to calculate 524x17 while walking.

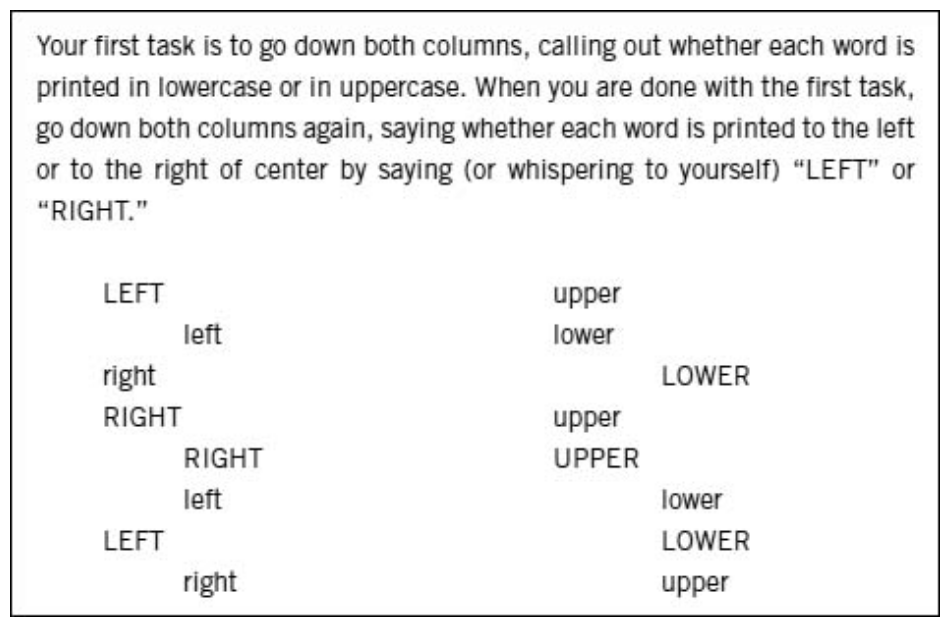

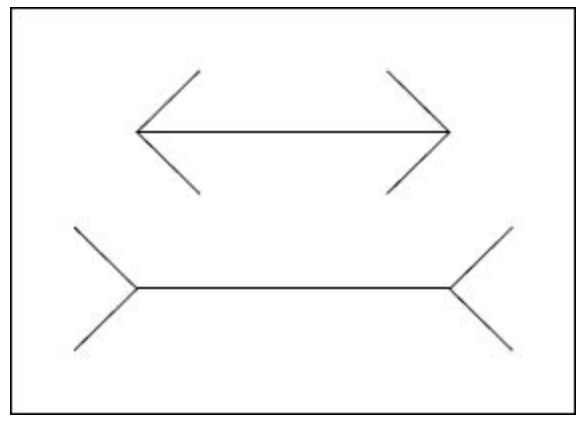

Try this before you read further

Which line is longer? System 1 tells that the second line is longer than the first. But System 2 would disagree (if you actually go ahead and measure both of them, you will know that they are equal)

The question here is — Can we ever overcome cognitive illusions like above. System 1 always operates automatically and is not in our control, making it hard to avoid biases — we are basically not just blind to facts, but are also blind about blindness. While System 1 has a lot of obvious advantages and it is impractical to be constantly questioning our own thinking, the solution is — to learn to recognise situations in which mistakes are likely and try harder to avoid those mistakes when the stakes are high.

Ego depletion

Self-control and deliberate thought depend on the same limited budget of mental effort. Participants of a study engaged in a cognitively difficult activity chose chocolate cake over fruit salad when presented with a choice. As self-control is tiring, if you forced yourself to do something, you are less willing to exert self-control on the next task (called Ego Depletion).

Sleeplessness also has a similar effect, resulting in lower self-control for morning people working late into the night and vice versa. The interesting part is — this mental energy is not just an idea but also a physical phenomenon. The mental effort is expensive in the currency of blood glucose, i.e. engaging in self-control or cognitively difficult tasks leads to a drop in glucose level. But the silver lining is that the effect of Ego Depletion can be undone by taking glucose — which is in line with why we have cravings for sugar at the end of a stressful day.

System 2 is lazy

Like physical exertion, there is a ‘law of least effort’ where we always try to minimise the mental effort needed.

Look at the puzzle below — do NOT try to solve it but just listen to your intuition

You are not alone if your mind first came up with 10c as answer

Even if you calculated the right answer (bat costs $1.05 and ball costs 5¢), the number 10¢ must have popped at least once in your mind. That is System 1 at work trying to minimise the effort.

The other consequence of a lazy System 2, as shown by multiple experiments, is— ‘when people believe that a conclusion is true, they are likely to believe arguments that appear to support it, even when these arguments are unsound’ This is really problematic because, conclusions come before arguments with an active System 1 that does not want to think.

Priming and ideomotor effect

Priming effect is the phenomenon where — If you have recently heard or read the word EAT, you are likely to complete SO_P as SOUP than SOAP. This is not limited to concepts and words, but your actions and emotions are primed by events which you aren’t aware. Labelled as ideomotor effect, examples are — when primed to think of old age, you tend to act old, and acting old reinforces thoughts of old age. This is also why the deliberate act of smiling uplifts our mood.

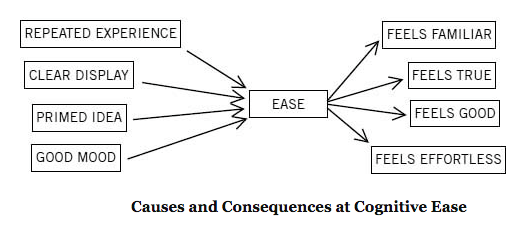

Priming is also a key input to increase cognitive ease — a state where you are comfortable in the atmosphere and your System 2 has let its guard down. It is easy to influence someone when they are in a state of ‘Cognitive Ease’ and this tactic has been used in retail for decades — good music, grouping items of similar colour, and well organised shelves create a comforting atmosphere that increases the likelihood of purchases. The inverse is true as well — experiments showed that when trick questions are presented in bad font that is hard to read, participants showed lesser likelihood to be tricked by the intuitive System 1. This is because cognitive strain, irrespective of its source (bad font in this case) triggers System 2, which is likely to reject the intuitive answer (Think about the importance of formatting in a good document or the neat-handwriting that we have all been told to master as kids, in order to score well in exams).

Another way to increase cognitive ease is familiarity — System 1 cannot distinguish familiarity from truth and often substitutes familiarity for truth (when not available). Continuous exposure to an idea increases familiarity and cognitive ease, and the reason is evolutionary — In a frequently dangerous world, an organism that reacts with caution and fear towards a novel stimulus has a higher chance of survival compared to one that is not suspicious of novelty. When the repeated exposure to a novel stimulus is followed by nothing bad, the organism adapts and marks the stimulus to be safe.

Jumping to conclusions and Halo effect

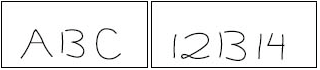

Read the characters

You must have read the first image as ABC and the second one as 12 13 14. Despite the middle item in both boxes being identical, you read them differently owing to the context. Sounds legit right? Now read below:

Alan: intelligent — industrious — impulsive — critical — stubborn — envious

Ben: envious — stubborn — critical — impulsive — industrious — intelligent

Most of us would have viewed Alan as having a favourable personality than Ben. The initial traits in the list change the meaning of the traits that appear later. The stubbornness of an intelligent person is respected but intelligence in an envious person is deemed dangerous. This tendency to like or dislike everything about a person is termed as halo effect. Because halo effect increases the weight of first observed traits, the sequence of traits observed in a person matters. Unfortunately, this sequence is usually determined by chance and often leads to incorrect evaluation of the people we meet (first impression is the best impression).

What You See Is All That Is (WYSIATI)

Another big factor that makes us jump to conclusions is System 1’s WYSIATI approach — What You See Is All That Is. System 1 is an associative machine — it excels at constructing the best possible story from the available information, with its measure of success being the coherence of the story it creates. This coherence-seeking nature of System 1 and a lazy System 2, together lead us to jump to conclusions when information available is minimal (which is usually the case). Consider the statement “Will Mindy be a good leader? She is intelligent and strong..” You’d say ‘Yes’ based on the limited information available (maybe the next two adjectives are cruel and corrupt, but WYSIATI — you made a coherent story with whatever is available). While such an approach is essential in day to day life, it has its downsides — one being Framing effect. The same information evokes different emotions when presented differently. ‘Odds of survival after one month of surgery are 90%’ is reassuring than ‘Mortality within one month of surgery is 10%’. While the alternative presentation can be easily deduced from the actual presentation, the individual sees only one presentation, and what she sees is all there is.

Substituting questions

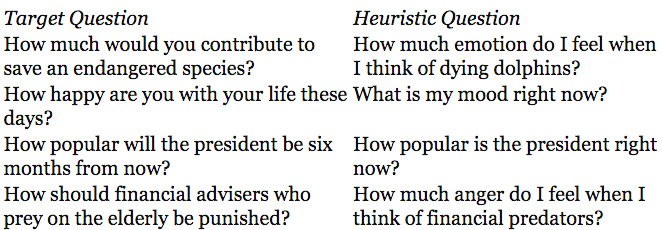

Often, when System 1 is posed with a hard question for which it cannot find an answer, it quickly finds a related and easier question and will answer it. Look at the below table — The column on the left shows the actual question we need an answer to. The ones on the right are what our System 1 uses as a substitute to get an answer.

But it is not sufficient to just find the answer to the easier question, the answer needs to be fitted back to the original question — I feel very bad for dying dolphins, but how much will I contribute in dollars? This is where System 1 uses its skill of intensity matching. Take the following example,

“Julie read fluently when she was four years old”

“How tall is a man who is as tall as Julie’s reading achievement?”

The answer you came up with is because of the ability of System 1 to form a scale of intensity (how extraordinary is Julie’s reading prowess) and match it across diverse dimensions (height of men). Similarly, the intensity of your emotions towards dolphins gets matched and translated to an equivalent dollar value that you’d contribute.

Now that you are aware of how the two systems in your head work, go ahead and observe your decisions. But remember that System 1 has a lot of obvious advantages and it is impractical to be constantly questioning our own thinking. Instead, learn to recognise situations in which mistakes are likely and try harder to avoid those mistakes when the stakes are high.

Part 2/5 of the book summary is here: