Over the past few years I’ve worn a lot of different hats: product manager, operations, designer, developer, etc.

But one of my favorite hats to wear is that of a writer.

After spending 4+ years studying technical majors in college, I rediscovered my love of writing in the months after graduation.

I began by blogging on the popular publishing platform Medium. I loved how easy it was for me to launch my own blog with just a few clicks.

The first time one of my blog posts went somewhat viral on the platform (to the tune of tens of thousands of views) I was instantly addicted.

Since then, I’ve gone on to expand my digital presence online through my LinkedIn product newsletter (41,000 subscribers) and even publishing my first book, Modern College.

However, despite all of the long-form content I’ve produced, I still don’t feel like there’s a great tool out there for writers. As a result, I often find myself getting discouraged and going through long droughts during which I don’t produce written artifacts for months.

I’ve decided I want to get to the bottom of this problem, and I figured a blog post highlighting the needs I have as a writer might help guide me in the right direction.

The Needs

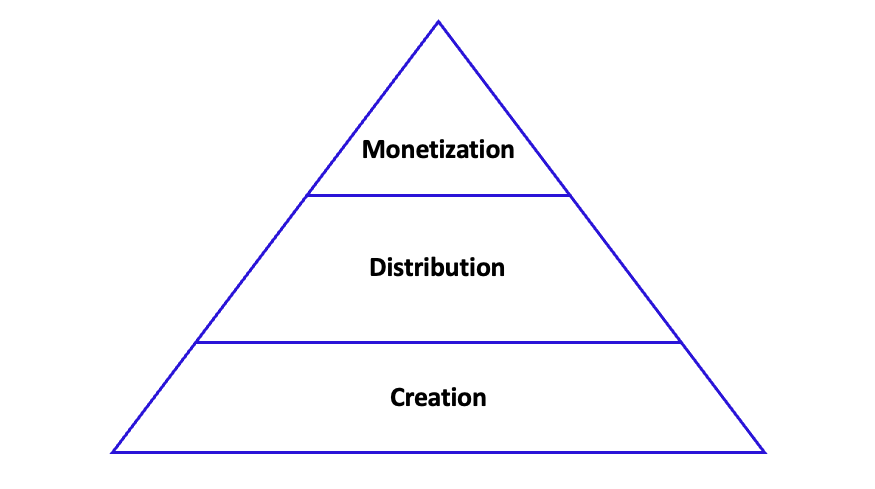

I created the simple image above for a previous blog post I published on Medium, called Reimagining Social Media.

Inspired by the famous Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, I argued that content creators had their own set of needs that also fall into a distinct hierarchy.

I believe this concept applies to writers (who are a specific type of content creators), so I wanted to dive deeper into the aspects that are unique to writers, and where the current tooling falls short.

Creation 🖋️

On the most basic level, writers need tools to actually create and publish their content. This involves a text editor, the ability to support different content types/embeds (images, native video, etc), and some sort of digital real estate upon which the content can live.

For the most part, this specific need has been commoditized, and is available on any serious publishing platform. This makes sense, because it is such a fundamental need, that without a solution for it, no writer would even be able to get started.

However, it starts to get more interesting when one considers where that content is actually hosted long term. This ties into an important nuance that is not often spoken about, which is who actually retains ownership of the content once it has been published?

If the content sits on servers that are owned by a centralized entity, then the writer never truly owns that content, despite it appearing as if they do. In most cases, this isn’t a problem and the sleight of hand makes the writer feel satisfied.

However, if a writer is ever deplatformed or wants to port their content over to a different platform, then it quickly becomes a major issue.

There is an inherent tradeoff here, as the paths for actually owning your content (personal website/blog) often have a higher barrier to entry than just using an out-of-the-box solution.

Medium recognized this dilemma for writers, and became a tech unicorn as a result.

Distribution 🌐

Once a writer has created a piece of content, his next need is the ability to distribute that content. After all, most writers spend the time to put their thoughts onto (digital) paper with the hopes that it will be read by as many people as possible.

More viewership = More influence = Greater chance of shaping the world to your vision

Distribution is an area that most writers struggle with, as it often involves knowledge of other domains (such as SEO and growth marketing) or a lot of effort to build an audience from scratch.

This was an area where Medium seemed to be solving well for my needs for some time, until suddenly my reach started to get throttled.

Whether this was caused by a dip in traffic to Medium.com, manual manipulation by Medium employees (unlikely but possible), or a change to the relevance algorithm, the problem remained the same, which is that less people started seeing my content.

I had made a rookie mistake, which is that I didn’t invest in actually owning my audience, which meant that I never fully controlled distribution of my content to that audience.

Substack sensed the friction between publishing platforms like Medium & its writers, and they decided to make a deal with the writers that would help win many of them over.

With Substack, writers get to (somewhat) own their audience by collecting their readers’ emails. This is definitely a step in the right direction, but certainly not the holy grail.

I think in a perfect world, writers would be able to truly own their social graphs. This would mean not only having the emails of their readers, but also owning the edges formed between their social identity and the social identities of their readers.

This would allow writers to have the best of both worlds, by still maintaining direct distribution to their readers, while also benefitting from the potential viral effects that large centralized platforms can provide.

Monetization 💰

Similar to artists, I don’t think the best writers are driven by money. If making money is your ultimate goal, there are much better ways to spend your time than writing. Not to mention, writing with the intent of making money can influence the positioning in a way that diminishes the overall quality of the final piece.

With that being said, I do believe that most writers would enjoy receiving payment for their work, and most readers would be open to spending some amount of $ for the content they consume.

Historically, there’s been a few problems with the monetization model for writers. The first, is that consumers have grown accustomed to paying for content via subscriptions that grant access to a large library of content. The concept of paying for one-off pieces of content isn’t something we’ve seen since the days of iTunes.

The second major issue is that the payments from readers tend to flow to the centralized entities that host the content and provide the services to writers. This is the price writers pay for giving up ownership of their content and social graphs, which are instead hosted (and subsequently owned) by the platforms instead.

This creates an extremely unfavorable power dynamic for writers, as they lose all leverage with the publishing platforms, who can in turn, arbitrarily decide what the details of the revenue share agreements look like. Almost always, these agreements are predatory in nature, and not in the best interest of the writers.

I don’t think any publishing platform has unlocked this final piece of the puzzle, and as a result, there is a huge opportunity for the first platform that can effectively do this.

If writers are able to directly monetize their audiences, it will incentivize both a greater quantity and quality of content to be published.

Conclusion

I have a lot of thoughts on how these needs could be met, by either innovating on existing business models or leveraging new technologies (like those available in the Web3 space) to make it happen.

However, before I dive into solutions, I want to make sure that these perceived gaps are common with a larger subset of writers. While I am a writer myself, I recognize that I am simply one data point among many.

If you are a writer, I would love to hear your thoughts on what I have outlined about. Please reach out to me over Twitter DMs if anything comes to mind.

-AV